To Kay, with love

Contents

Magnanimity in politics is not seldom the truest wisdom.

E DMUND B URKE

Mankind will at length, as they call themselves reasonable creatures, have reason and sense enough to settle their differences without cutting throats.

B ENJAMIN F RANKLIN

Revolution on the Hudson

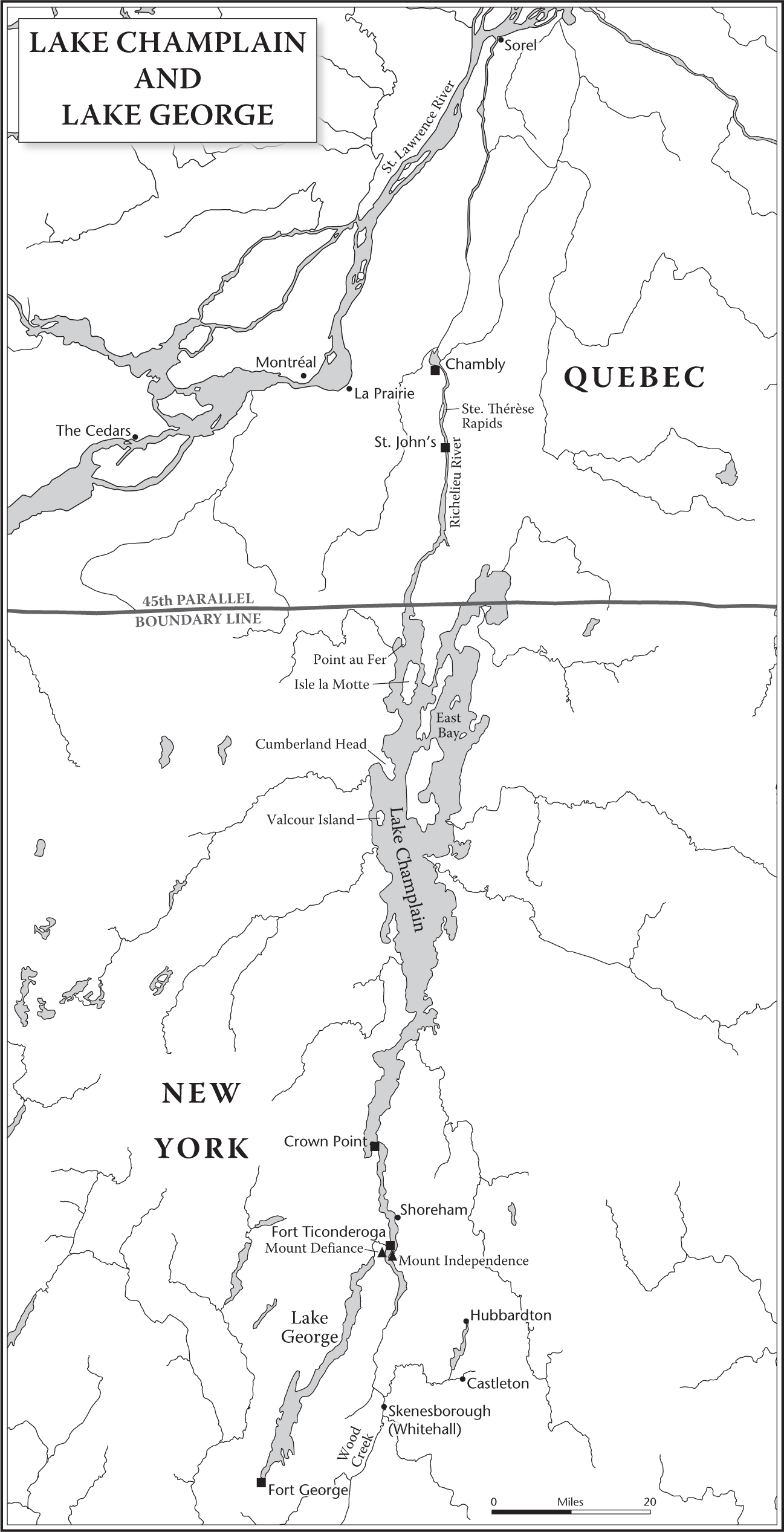

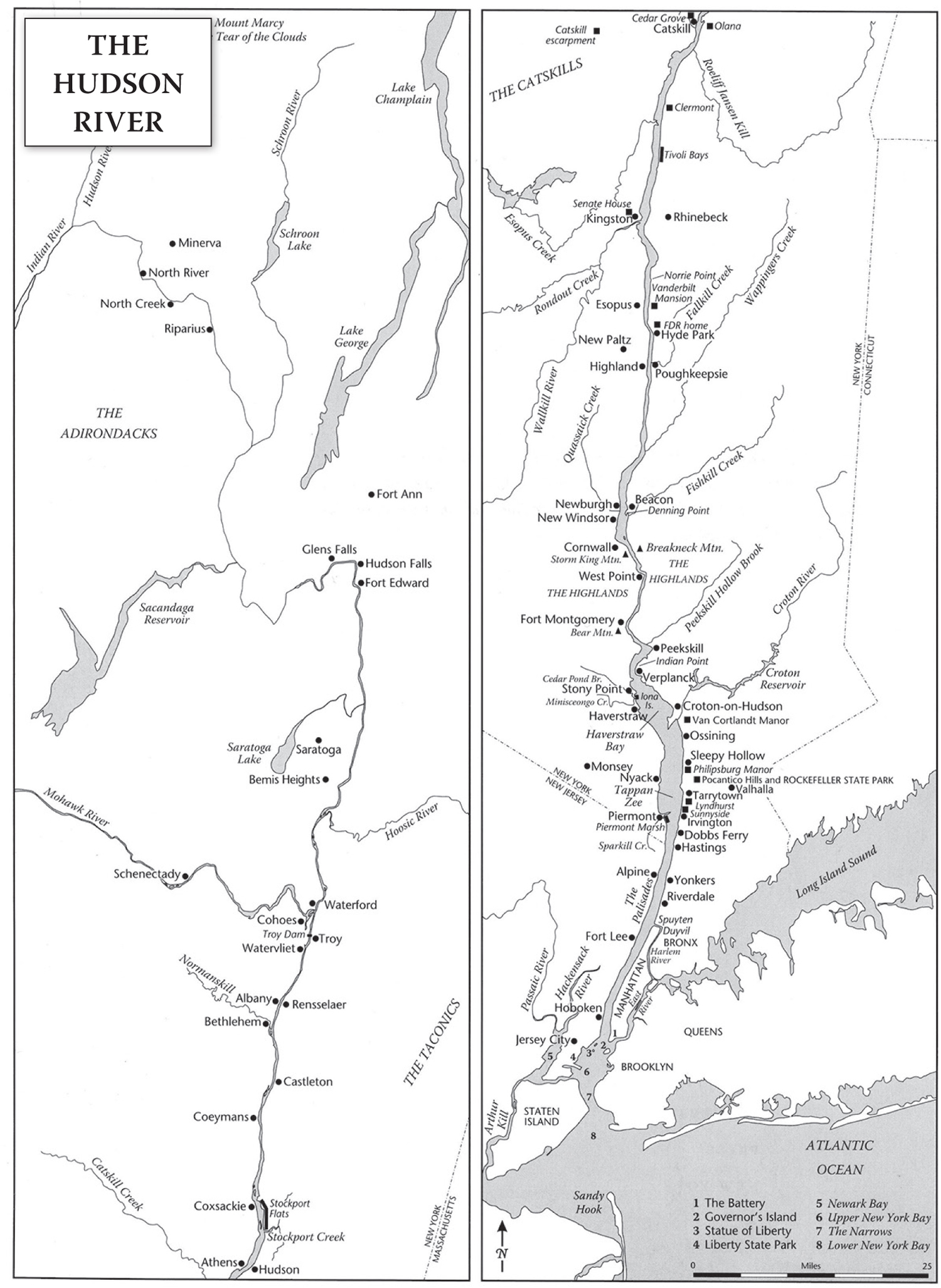

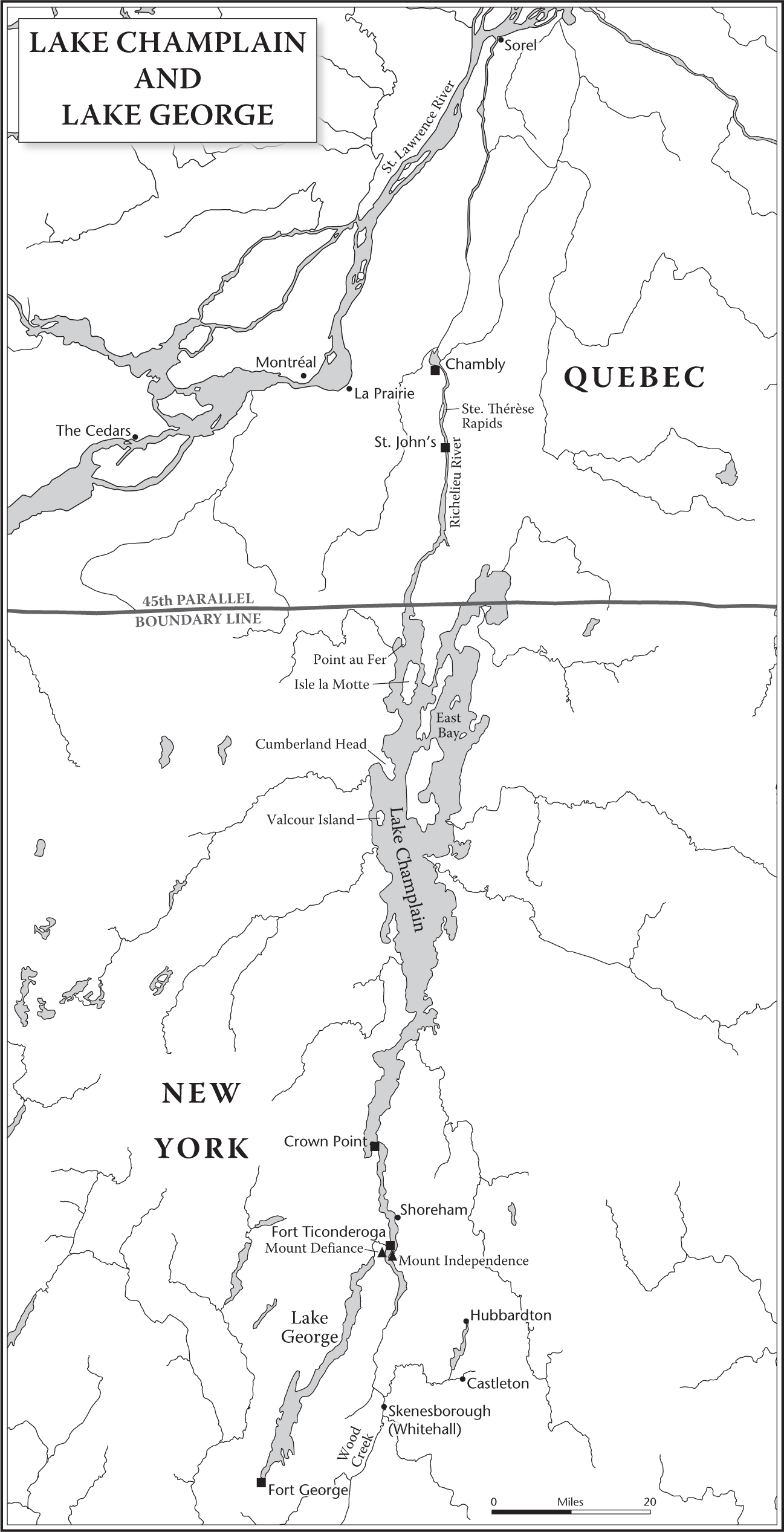

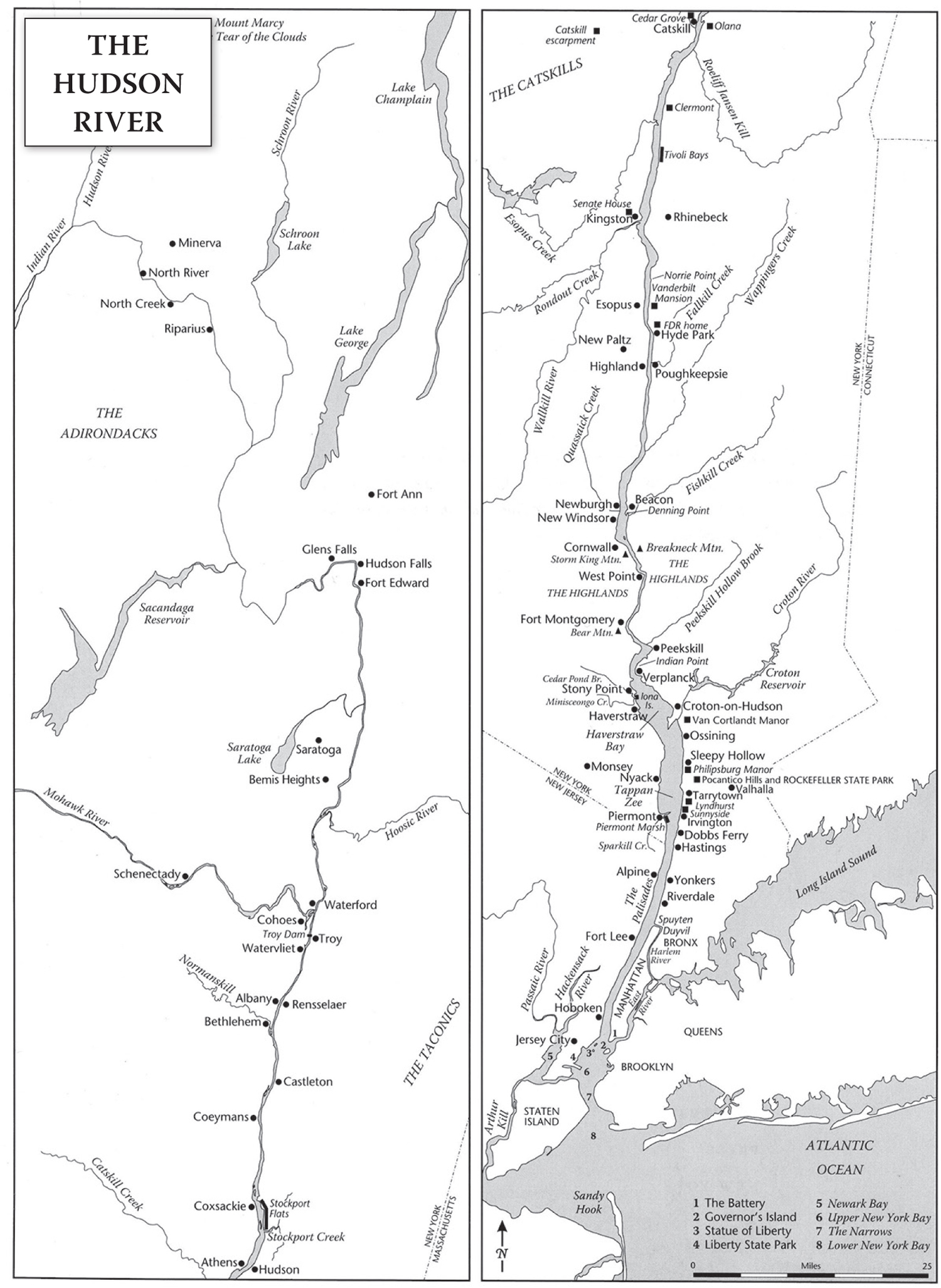

S ize, location, an extensive harbor, sophisticated port facilities, and a large population put Manhattan and the Hudson River at the center of the War of Independence. Not only was New York City and its environs one of the most vibrant urban centers in America, it was also the beginning of a unique watery highway that extended deep into the interior of the continent, linking Manhattan with Quebec. Navigable water ran nearly the entire way from New York Harbor to the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. The only significant interruptions were the few miles of land connecting the Hudson with Lake George: the boisterous three-and-a-half-mile La Chute River that emptied Lake George into Lake Champlainwhat Native Americans called the place between the watersand the ten miles of rapids on the Richelieu River between Saint-Jean and Chambly.

To anyone looking at a map in London, this striking sea-land corridor appeared to form a natural boundary between New England, the epicenter of the revolt, and the less militant colonies to the south. Since the Royal Navy was the unquestioned mistress of the sea, and Britain already possessed Canada, it looked to George III and his advisors that by seizing the passageway connecting Manhattan with Canada they could isolate New Englands radicals, destroy them, and end the rebellion in a single campaign season.

That season was to be 1776. After failing in 1775 to crush the revolt in Massachusetts with a tiny army, His Majesty decided to go all out in 1776 and send the largest amphibious force ever assembled to seize Manhattan. His armada would then use it as a base from which to push north up the Hudson River Valley for a grand rendezvous at Albany with an impressive army driving down from Canada under General Guy Carleton via the St. Lawrence, the Richelieu, Lake Champlain, Lake George, and the Hudson.

As the king imagined it, the junction of the two armies would isolate New England and leave it vulnerable. From Albany the combined forcesover twenty thousand strongwould invade Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island, radically altering the political landscape. Once New England Loyalists saw Britains awesome power, His Majesty was convinced they would flock to his banner, as would political fence-sitters, while rebels would be cowed. He expected that radicals in the Mid-Atlantic and the South would then lose heart and return to their allegiance.

Without being fully aware of it, the king was making three critical assumptions. The first was the capacity of the Royal Navy to impose a tight blockade along the entire New England coast, while at the same time supporting an amphibious force pushing up the Hudson River Valley and the one marching from Canada. He also assumed that the navy could maintain a continuous presence all along the Hudson, as well as provide support for permanent posts that the army would be establishing at key points along the route linking New York and Canada. Belief in the prowess of the navy was such that its ability to perform this outsized task was never questioned.

The second assumption concerned colonial politics, which His Majesty studied carefully, albeit with little understanding. He had long since concluded that the armies he was sending up the Hudson and down from Canada would meet with enthusiastic support along the way. He felt that most Americansincluding New Englandersunderstood the unique benefits a great empire provided, and were generally loyal to him. They only needed a strong military presence to regain power in their provinces from the tiny coterie of radicals who had usurped them.

The third assumption was that Britain could accomplish her objectives through military means alone. Since the king believed that Loyalists were already the majority, there was no need, in his view, to offer any concessions to win over the rest of the colonists. All His Majesty had to do was crush a vocal, self-aggrandizing minority. Brandishing the sword appeared to be the quick way to victory.

Although isolating New England from the rest of the colonies seemed to be the perfect strategy, it unaccountably failed in 1776. Blame was placed on poor execution, however, not on the concept. Convinced that he was right, the stubborn monarch employed the same approach, with modifications, in 1777. When his plan failed again, the culprit was deemed to be, once more, poor implementation, not the strategy. In fact, since the kings armies never actually met at Albany in either year, the theory continued to fascinate and attract because it was never really tested.

The entrance of France into the war in 1778 forced George III to drastically revise his overall strategy. Instead of focusing on New York, he shifted emphasis to the West Indies and the South. New York City would still be the principal base of operations, but British efforts would now be directed mainly at the southern provinces, which were thought to be easier to conquer and control.

In spite of this change, fascination with seizing the Hudson River Valley as a fast way to end the conflict persisted and had a profound effect on the rest of the war, becoming, in the end, one of the principal reasons Britains military effort failed. Indeed, the idea was so powerful it did not die when the war ended. It became one of the enduring myths embedded in all accounts of the Revolution. Students of the war, without exception, took it for granted that British control of the HudsonLake Champlain corridor was possible, and that it would have severed New England from the rest of the colonies, with fatal results for the rebellion. The fact that no armies ever met at Albany, that the idea was only a hypothesis, helped give it a long life.

The great naval historian Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan was as attached to the theory as every other scholar. He argued that the strategy would have worked had it been executed properly. The difficulties in the way of moving up and down such a stream [the Hudson], he wrote, were doubtless much greater to sailing vessels than they now are to steamers; yet it seems impossible to doubt that active and capable men wielding the great sea power of England could so have held that river and Lake Champlain with ships-of-war at intervals and accompanying galleys as to have supported a sufficient army moving between the headwaters of the Hudson and the lake, while themselves preventing any intercourse by water between New England and the states west of the river.

Probably the most important reason historians accepted the viability of the kings strategy was that George Washington and every other patriot leader shared His Majestys fixation with the Hudson. They were just as certain as he was that Britain was capable of seizing the HudsonChamplain corridor and that, if she did, New England would be cut off and the rebellion ended.

Next page