Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Franklin & Marshall College for the sabbatical during which I wrote most of the pages that follow, and also for the colleges support of my research and teaching over the course of thirty-eight years. During that time many F&M students have helped me in my research on different scholarly endeavors, largely through our wonderful Hackman Scholars program, endowed by alumnus William Hackman, which supports students in collaborative research with faculty. In writing this book I have been fortunate to have two Hackman Scholars work with me. Molly Cadwell helped with the research at the beginning of this project, and I am proud that she transformed what she learned into a superb honors thesis on Storm Kings significance to American environmentalism. Wyatt Behringer also contributed to the research and was instrumental in the early stages of checking the text and notes.

For financial support in conducting research I am indebted to the Archives Partnership Trust, which enabled me to conduct research in the New York State Archives, especially the records of the Hudson River Valley Commission, and to the Rockefeller Archive Center, where I consulted the Hudson River Valley Commission records and, more revealingly, two boxes of Laurance Rockefellers papers that had not been cataloged. I am grateful to archivist Monica Blank for finding and making accessible the Laurance Rockefeller papers relevant to this book, and to Jim Folts for his help during my visit to the state archives.

Many people in the Hudson River Valley have also been extraordinarily helpful. I am deeply indebted to Thomas Wermuth, dean of the faculty and director of the Hudson River Valley Institute at Marist College, where I was the first Barnabas McHenry Visiting Scholar during the fall semester of 2015. I am also indebted to John Ansley and the staff at Rare Books and Special Collections, James A. Cannavino Library, especially Ann Sandri, for making its terrific Hudson River environmental collections accessible. Harvey Flad, a friend for many years and now retired after a distinguished career at Vassar College, generously shared his research files on the Cementon case, gave me the benefit of his encyclopedic knowledge of other environmental battles in the valley, and commented on a draft of this book. Ned Sullivan and Reed Sparling of Scenic Hudson have done so as well. Paul Gallay of Riverkeeper welcomed me to his office and answered innumerable questions that helped me frame that chapter. He too commented helpfully on an earlier draft.

I could not have written this book without the help of many individuals in the Hudson River Valley who shared their knowledge of important developments. J. Winthrop Aldrich, now retired but the longtime deputy commissioner for historic preservation in New York, knows most of these issues firsthand, as he was involved in many of the conservation and environmental battles I analyze. Wint answered innumerable questions as I was struggling to understand those issues, and also commented on the entire typescript in draft. I had never met Albert K. Butzel, who is one of the individuals most responsible for the development of U.S. environmental law, but when I sent him an e-mail he responded welcomingly, and since that first exchange his thoughts have guided me as I have written many of the pages that follow. Al also read a draft of this book, and I am indebted to him for his thoughtful, constructive criticism. John Cronin shared with me his vast knowledge of many of the organizations and issues I have written about, and commented helpfully on an earlier version of this book. Adam Romes reading of a draft challenged me to place the environmentalism of the Hudson River Valley into a national context. Tom Daniels and Steve Schuyler also read this in draft and helped me in many ways.

Betsy Garthwaith, formerly Clearwater s boat captain and now president of the organizations board of directors, read the Clearwater chapter and helped me when I was assembling the illustrations; Karl Beard and Barnabas McHenry offered sage advice on the Greenway and NHA chapter; and John Mylod shared his recollections of the years in which he was executive director of Clearwater and offered helpful comments on that chapter.

Others who have helped include Mark Castiglione, who for many years headed the Hudson River Greenway / Hudson River National Heritage Area; John Doyle, formerly director of the Heritage Task Force of the Hudson River Valley; and Frances Dunwell of the Hudson River Estuary Program. Maynard Toll put me in touch with his old friend Leon Billings, who gave me invaluable insight into the politics surrounding adoption of the National Environmental Policy Act. Conversations or correspondence with Hayley Carlock, Carl Petrich, Tom Whyatt, Frederic C. Rich, and Loretta Simon were very helpful in my understanding of important issues I have written about. Sam Pratts knowledge and advice helped me analyze the St. Lawrence Cement controversy, as did conversations with Sara Griffen. Peter Brown shared with me his copy of Nuclear Power in the Hudson Valley: Its Impact on You .

My colleagues at Shadek-Fackenthal Library were enormously helpful in my research, especially Meg Massey and Jenn Buch in Interlibrary Loan. American Studies colleagues Louise Stevenson, Alison Kibler, Carla Willard, and Dennis Deslippe were supportive in many ways during this scholarly journey.

I spent most of the fall of 2015, when I was at Marist, as a guest of my oldest brother, Barry, and his wonderful spouse Jodi. They gave me their extra bedroom and a smaller one where I hooked up my computer and worked many nights. They have also welcomed me on subsequent research trips as well as visits home for the holidays. Their house overlooks the Hudson just north of Newburgh, the same vista, looking east toward Mount Beacon and south toward Storm King and Breakneck Ridge, that I came to love as a child. Visits to their home, and their welcoming embrace, as well as the scenery so remarkable from their windows and porches, remind me of why I still, after so many years away, consider the Hudson Valley home.

To all I am deeply grateful.

Introduction

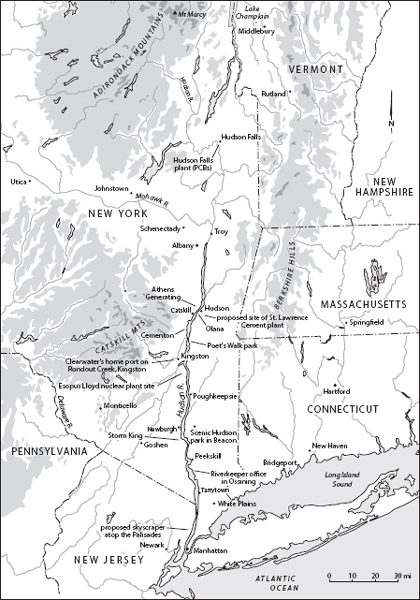

Since 1962 the Hudson River Valley has been a key battleground in the development of modern environmentalism in the United States. What began with a small group of individuals opposed to Consolidated Edisons plan to construct a pumped-storage power plant at Storm King Mountain, the northern gateway to the Hudson Highlands, quickly attracted supporters in the region and across the nation. That small group organized as the Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference and successfully waged a legal and public relations campaign against the powerful utility that established the foundations for environmental law. Other groups organized as well, sometimes in response to a specific threat, at other times with a broader mission to defend water quality, such as Riverkeeper, or to promote environmental education, the replica nineteenth-century sloop Clearwater s mission. Through their collective efforts, these organizations have defended the valleys environment and worked to promote the quality of life and the economic vitality essential to its residents.

The Hudson is a comparatively short river. It flows south from Lake Tear of the Clouds on Mount Marcy, the highest peak in the Adirondacks, for 315 miles until it reaches the Atlantic Ocean. It flows by the Catskills, which attracted the first generation of artists who defined an American landscape tradition, named after the river itself, as well as the Highlands, a visually spectacular fifteen-mile stretch where the river courses through the mountainous Appalachian spine. It broadens into a bay three miles wide at the Tappan Zee, memorialized in Washington Irvings prose, and flows past the Palisades and New York City before reaching the sea.