The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This country is so heated up about communism at the present moment that the public temper identifies as a friend of the United States any person who is a foe of Stalin.

Personal relations are despised today. They are regarded as bourgeois luxuries, as products of a time of fair weather which is now past, and we are urged to get rid of them, and to dedicate ourselves to some movement or cause instead. I hate the idea of causes, and if I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.

Loyalty means nothing unless it has at its heart the absolute principle of self-sacrifice.

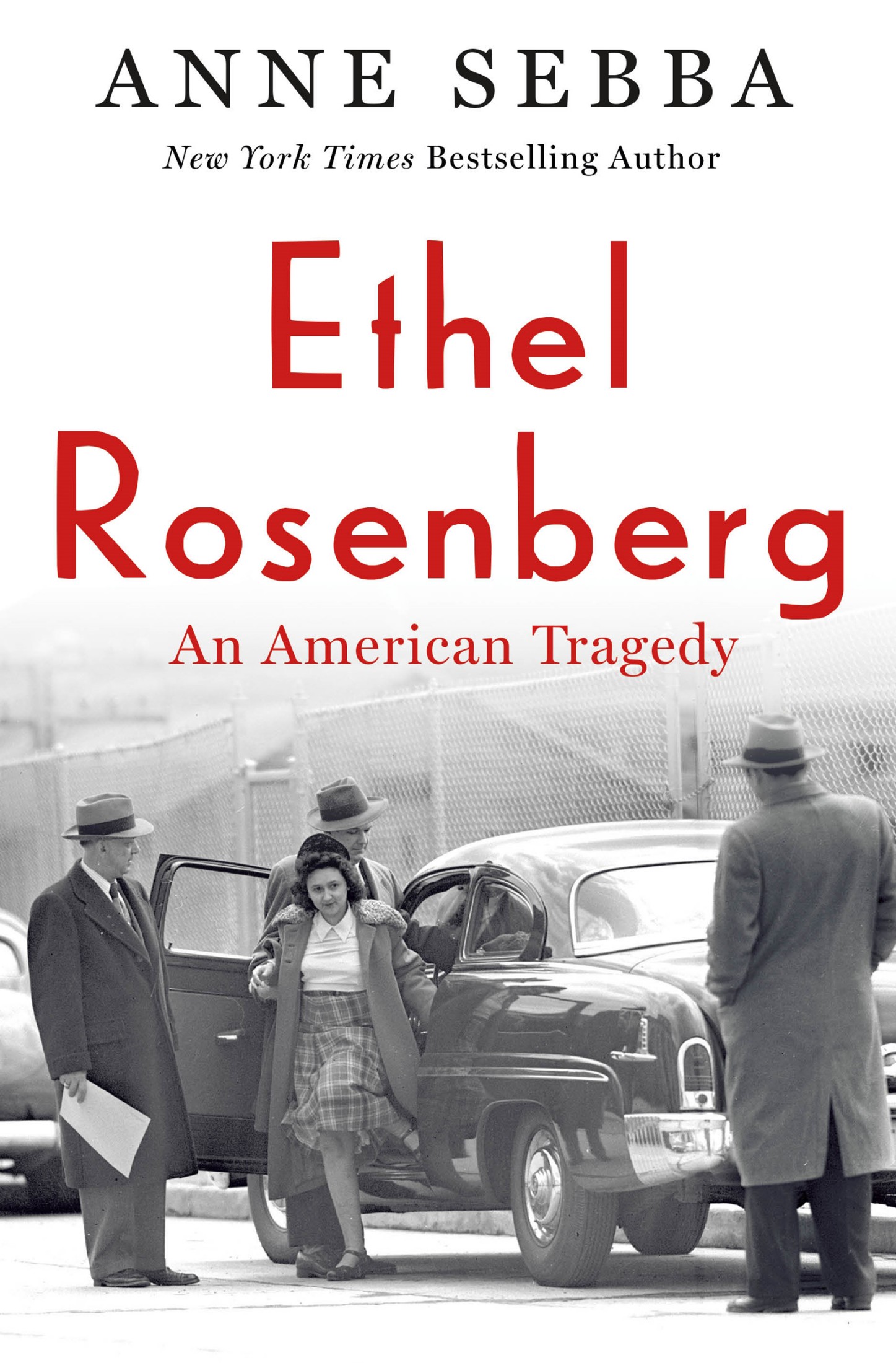

Friday, June 19, 1953, dawned typically hot and humid in New York, the sort of day later memorably described by the poet Sylvia Plath as sultry. Occasional bursts of sunshine seemed to promise something better, but it was a promise stubbornly unfulfilled. In Washington there was even light rain.

But the weather made little difference to one young couple, who spent the day inside, behind bars, in the condemned cells of the womens wing at New Yorks high-security Sing Sing Prison, at least allowed to communicate with each other from noon until 7:20 p.m. through a wire mesh. It was the day after their fourteenth wedding anniversary, when together they had composed a last will and testament and final instructions to lawyers. Words fail me when I attempt to tell of the nobility and grandeur of my lifes companion, my sweet and devoted wife, he told his lawyer in shaky handwriting with frequent crossings-out. Ours is a great love and a wonderful relationship. It has made my life rich and full.

That Friday, their last day of life, they wrote heartbreaking farewell letters to their two sons, Michael, aged ten, and Robby, six, our pride and most precious fortune. Ethel Rosenberg, thirty-seven, believed deeply that she was not only innocent; she wanted to be morally correct, on the right side of history.

She then left her boys with some carefully chosen literary quotes, penciled on a scrap of prison paper, for them to ponder, including the following: Geo Eliot said, This is a world worth abiding in while one man can thus venerate and love another; and Honor means that you are too proud to do wrongbut pride means that you will not own that you have done wrong at all.

Juliuss personal effects had been boxed up into three cartons and left with the warden. Ethel owned little more, and the inventory of her meager possessions at the time of her death included deodorant, stockings, and a shoebox of letters from her children. At the time of their arrest the FBI had confiscated most of the couples possessions, including all family photographs. She asked their lawyer, Emanuel Hirsch Bloch, to ensure that her children received her Ten Commandments religious medala gift from a friend she had made in her first prisonand her wedding ring.

Once the final requests for clemency had been denied, the establishment was in a rush to get on with the executions after almost three years of imprisonment for the couple. The executions had been set for 11 p.m., the usual time at Sing Sing. But Bloch appealed to the trial judge, Irving Kaufman, not to execute the Rosenbergs that evening as it was the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath. Both he and Rabbi Koslowe, the seventy-five-year-old Orthodox Jewish chaplain at Sing Sing who had grown close to the Rosenbergs over the last two years, were now fighting for extra hours. Koslowe had spent Friday helping the young couple prepare to die in the electric chair, but nonetheless never gave up hope that he could prolong their lives. The priority is life, even one minute of life, he said. If I can prolong a life by one minute I am duty-bound by Jewish law to do so.

But he failed. Judicial officials, insisting they were showing their respect for the Jewish Sabbath, decided to execute them three hours earlier than the schedule called for. This accelerated timetable forced the prison to dispense with the traditional last meal. Julius was instead offered an extra pack of cigarettes. Ethel did not smoke.

As the hour approached, heavy details of police and state troopers were brought in to protect Ossining, the town bought in 1685 from the Sint Sinck tribe. Sing Sing prison still stands there today, located on a steep hill of white marble overlooking the Hudson, thirty miles north of New York City. In other circumstances, a most beautiful spot. Two telephone lines were opened between the office of prison warden Wilfred Louis Denno and the White House in Washington. A party of five legal witnesses and three reporters arrived and were told to sit on four rows of benches resembling church pews. There had been a panic to locate the executioner, Joseph Francel, who had thought he would not be needed until 9 p.m. But even that minor crisis proved in the end not too difficult to overcome. Francel arrived well before sundown and was stationed in an alcove to the left of the room.

Having been assured that all the necessary signatures for the rental of the wooden chair with leather straps from the State of New York had been obtained and that voltage tests had just been carried out to his satisfaction, there was one further check required. This was to ensure that, should either of the condemned prisoners decide to make a last-minute confession or name names, the line-of-sight arrangements between FBI agents and the warden were active so that the execution could be immediately stopped. But Ethel and Julius refused to the end to trade secrets or name other names to save their own lives.

The authorities had debated which of the pair to execute first. The warden was in favor of Ethel, believing that Julius would, at the eleventh hour, break down and deliver the longed-for confession. But J. Edgar Hoover, the long-standing FBI director with one eye on public opinion, had all along been against the death penalty for Ethel, and was now especially alive to the criticism that would attach to the FBI if, after she were killed, Julius, the husband and father, repented and his life had to be spared. Nothing would embarrass the Bureau more than to have the wife and mother of two children die and husband survive. It would be a public relations nightmare. Anyone with any knowledge of Ethel knew the impossibility of her either repenting or recanting if her husband had been killed; she could never have lived with herself under those circumstances.

And so at 8 p.m. Rabbi Koslowe, in his long black robes and white prayer shawlintoning the words of the 23rd Psalm, The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not wantled the thirty-five-year-old Julius Rosenberg from his holding cell, in an area of the prison incongruously referred to as the dance hall, into the execution chamber. Juliuss mustache had been shaved off, his glasses removed, and he turned without guidance to sit in the electric chair. A black helmet was placed on his head, black straps fixed around his chest, and electrodes placed on his right leg. The warden signaled to his aides to flick the switch that would send three massive charges of electricity through the mans body. Minutes later two doctors with stethoscopes declared Julius Rosenberg was dead.