Contents

Guide

Page List

CONTENTS

FOREWORD: BONG JOON-HO

I tend to classify the films I watch into two types: the linear type and the curvilinear type. Its a highly subjective method of classification, and the division I impose is severe, perhaps even violent.

But Im not an expert critic writing for Film Comment or Cahiers du Cinma so I hope readers will forgive the crudeness of my method.

Some films abound with curves. From the characters to the movement of camera to the mise en scne and music, we are enveloped by waves and circular motions. These are the curvilinear films.

Some films are strongly dominated by sharp lines and angles throughout their running time. These are the linear.

For me, Fellini and Kusturica exemplify curvilinear filmmaking while Stanley Kubrick and David Fincher are masters of the linear.

Fincher, especially, pushes beyond the linear and cuts us with such razor-sharp precision that it almost hurts our eyes and hearts to watch.

In fact, whenever I finish watching one of his films, I feel like my heart is bleeding from its corner.

His exactingly beautiful camera movements leave haunting, lasting impressions while the fiercely self-assured compositionwhere no other angle or framing is even imaginablegives you complete satisfaction. The camera and subject always move in parallel, maintaining the perfectly measured distance, never engaging in a needless tug of war.

The purity of cinematic excitement derived from these moments more than compensates for the figurative blood that is shed.

I do not wish to talk about extreme examples like the stunning overhead shot of the yellow cab in Zodiac (actually a VFX shot), where the camera makes a seamless 90-degree turn with the car, the target of the serial killer, in perfect synchrony.

Since the days of his awe-inducing music videos and early features like Alien 3, Se7en, and Fight Club, David Fincher has unquestionably been the greatest stylist and technician.

But Id rather talk about the much more plain, unflamboyant shot of Jake Gyllenhaal staring at John Carroll Lynch in the hardware store near the end of the film.

Or when Jesse Eisenberg blankly stares at his laptop waiting for a reply from Rooney Mara in The Social Network. A response that never comes.

These are the moments that quietly deliver the deepest cuts, causing us to bleed helplessly.

In those classic and (seemingly) ordinary shots, our unconscious is violently shaken and our hearts sharply pierced in the middle.

Its a long, straight, precise cut that only David Fincher can administer, and we are left with a beautiful cinematic scar.

March 16, 2021

Bong Joon-ho

AN INTRODUCTION

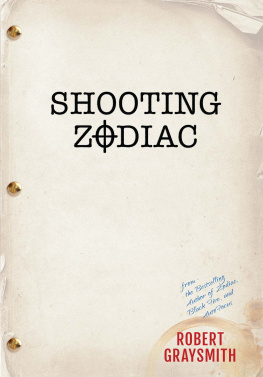

1. THE MOST DANGEROUS GAME

Robert Graysmith: Man is the most dangerous animal of all... I knew Id heard that somewhere. The Most Dangerous Game! Its a movie about a guy who hunts people for sport. People! The most dangerous game! Paul Avery: Whos that guy there?

Robert Graysmith: Thats Count Zaroff.

Paul Avery: Zaroff? With a Z?

Early on in David Finchers Zodiac (2007), newspaper cartoonist Robert Graysmith connects the cryptic, coded messages and astrological pseudonym of an elusive serial killer to the villain of the 1932 horror classic The Most Dangerous Game, about an aristocratic psychopath who conceives of leisure time as a matter of life or death.

The films of David Fincher are filled with dangerous games and apex predators: Think of Kevin Spaceys John Doe in Se7en (1995), Gods Lonely Man meting out Biblical punishments until a real rain comes to wash the scum off the streets; or Gone Girls Amy Dunne (2014), marionetting the people around her in a live-action Punch-and-Judy show. Sinister conspiracies proliferate in The Game (1998) and Fight Club (1999), paranoid thrillers whose protagonists come to wonder whos been jerking them around, and why. Elsewhere, the directors protagonists bristle with exceptional, rebellious intelligence: what connects Fight Clubs insurgent Tyler Durden to The Social Networks (2010) squirmy Mark Zuckerburg to the deadpan heroine of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) is a skepticism about the status quo and a desire to disrupt it, whether by building systems, penetrating them or crashing them to the ground.

Few directors are as fascinated by the idea of high-level, top-down controlfrom the panopticonal prisons of Alien 3 (1992) and Panic Room (2002) to the power-gaming political machinations of House of Cards (20132018)and few are as equipped to exercise it. Over the past thirty years, Fincher has cultivated and maintained a reputation that precedes him of formal rigor and technocratic exactitude, of moviemaking as a game of inches. In 1939, surveying the backlot at RKO, Orson Welles said that the cinema was the biggest electric train set any boy ever had; the most succinct way of defining the cinema of David Fincher might be to say that, on his watch, the trains run on time.

2. THE EYES OF ORSON WELLES

In 1943, the popular CBS radio program Suspense aired an audio-play adaptation of The Most Dangerous Game starring Orson Welles as Count Zaroffa superb piece of casting drawing on the stars fame as Lamont Cranton in The Shadow, the phantasmic vigilante claiming to know the evil that lurked in the hearts of men. A few years earlier, in 1940, Welles had been planning a film version for RKO of Joseph Conrads novel Heart of Darkness, also about a mad exile presiding over an isolated kingdom; in 1942, after decamping to Brazil to shoot the ultimately unfinished Pan-American odyssey Its All True, Welles had become perceived as an American Kurtz, an idealistic iconoclast playing dangerous games with studio money.

Few filmmakers have ever been as magnetic, onscreen or off, as Welles, which is why he has been impersonated in so many period pieces and biopics over the years. There exists an entire subgenre of what might be called Welles-centric cinema, with Finchers 2020 drama Mank as the latest and most contentious contemporary addition. In it, Welles is played by the British actor Tom Burke and stares out at the world with a lazy, half-lidded confidence in his own supremacy. Until hes challenged, at which point his dark pupils blaze and dilate, combining with his close-cropped Caesar haircut and goatee to give a man referred to in the film by his collaborators as a dog-faced prodigy a devilish aspect. This Welles is glimpsed mostly in swift interstitials which gesture towards his yearning to play Kurtz, as well as his incarnations in The Shadow and The Stranger (1946), and the hard-driving tyro of Citizen Kane (1941)the film whose genesis serves as Manks backdrop. But his appearance suggests another filmmaker as well. As Rolling Stone