Contents

Guide

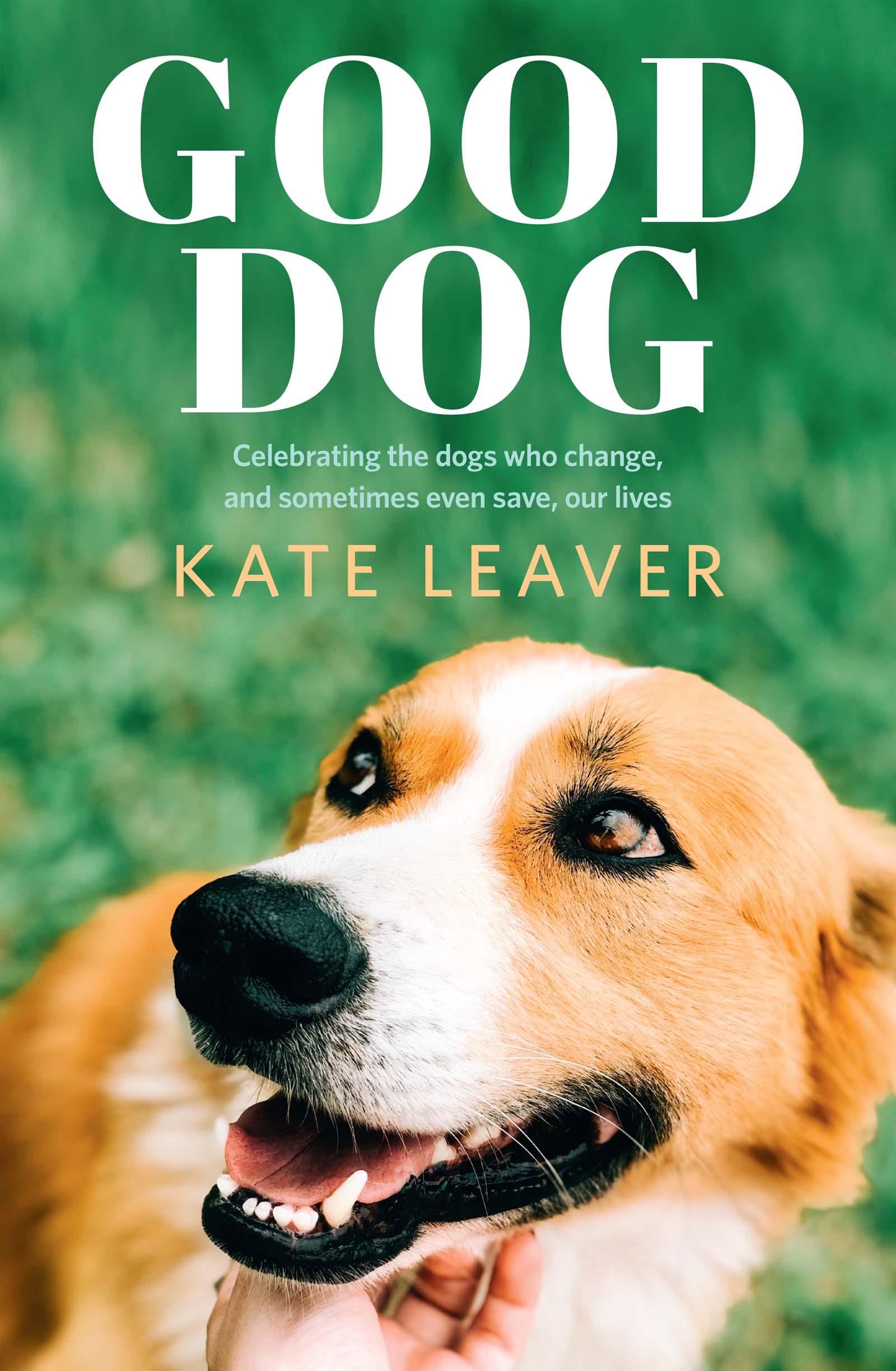

KATE LEAVER is an author and journalist for The Guardian, The Telegraph, Vogue and Future Women, among others. She lives between Sydney and London with her boyfriend, Jono, and their dog, Bertie. You can find her on Twitter and Instagram @kateileaver.

HarperCollinsPublishers

First published in Australia in 2020

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Kate Leaver 2020

The right of Kate Leaver to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000.

This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale 0632, Auckland, New Zealand

A 75, Sector 57, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201 301, India

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower, 22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor, Toronto, Ontario, M5H 4E3, Canada

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, USA

ISBN 978 1 4607 5889 2 (paperback)

ISBN 978 1 4607 1262 7 (ebook)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

Cover design by Darren Holt, HarperCollins Design Studio

Front cover image by Stephanie Reis/Getty Images

To my grandma Lyn James, the only person Ive ever known

who loved dogs as much as I do.

Contents

SHALL WE BRING OUR firstborn son with us?

Dont call him that. Hes a dog.

But I love him like he is my child. Hes my hairy, grubby little child.

I get in trouble with my boyfriend whenever I refer to our dog, Bertie, as my firstborn son. The anthropomorphism is a bit much, even for him, who otherwise adores our small, smelly companion as much as I do. I cant find another way of conveying how serious I am about my affection for our 58-centimetre-long hairy housemate. He is a living creature, roughly the size of a big new-born human, who depends on us for food and love and warmth and safety. The way he nuzzles his wet nose into my neck while we watch telly at night makes me feel maternal. Im not a mother, so this is the most powerfully responsible Ive ever felt for a breathing, snuffling, snoring, farting being. Besides, I find it funny to wind my boyfriend up.

Im not entirely mad, though. Every time I whisper Whos my baby boy? into my dogs floppy, silver-tipped ears, I am simply verbalising a complex bond between two species that has existed for tens of thousands of years. The remains of a dog from 14,000 years ago were found buried beside a family of humans in Germany; a proximity in death that implies a life lived together. Archaeologists have found dog bones that were buried lovingly beside humans in Siberia 8,000 years ago, and North America 9,000 years ago. Chemical analysis has revealed that these dogs ate the same food as their accompanying humans, meaning they were well cared for and fed. They were treated, in some ways, as equals. Human beings used to kill and eat dogs, too, but in most cultures that stopped once people started treating dogs as beloved companions, status symbols, working dogs and members of the family. With protection from human beings, dogs have been substantially more evolutionarily successful than their original ancestor, the Eurasian grey wolf. Its less about survival of the fittest, more about survival of the cutest.

Experts squabble over exactly what prompted wolves to evolve into human-friendly dogs. Some say that humans enlisted wolves to hunt for them, but actually wolves are not the kind of species to give up food once they have chased it down. Its more likely that a very long time ago somewhere between 14,000 and 33,000 years ago, according to feuding scientists wolves started following packs of humans, probably hoping to pick up a few food scraps. Humans recognised the wolves potential usefulness as hunters and guardians, so they learned to work together as a team and then share the food. They would also have relied on these companion wolves/prototype dogs to warn them of danger, too, by barking at any strangers, intruders or unwelcome beasts who approached their tribes home. Archaeological evidence tells us that when humans migrated across the planet, they took their canine pals with them. The friendlier among these wolves became true companions, protected and treated with affection. Friendly wolves bred with friendly wolves, which ultimately resulted in the dog, a slightly genetically different creature.

These creatures started evolving alongside us, getting closer to the cuties we coddle these days. Gradually, their ears got floppier, their tails got waggier and their coats became splotchy. The closeness between dogs and our ancestors even affected the way their brains developed and possibly ours. Some scientists argue that we humans have a diminished sense of smell because we have formed such a close bond with dogs, who can do some of our sniffing for us. Meanwhile, dogs have learned to widen their eyes and behave adorably to catch and then keep our attention. Putting on their cutest possible facial expression increases their chance of survival, getting affection and delicious treats. Over centuries, we have forged a symbiotic relationship with our canine friends, exchanging protection, affection and companionship.

While dogs certainly used to help us track down other beasts for mealtimes, a crucial part of their appeal has always been their cuteness. Im not the only one whos had her parenting instinct triggered by a puppy; human beings have long doted on dogs in a pseudo-parental sort of way. Its why our ancestors held burial rituals for them. Its why they brought dogs along with them when they moved homes. Its why experiments have demonstrated that we have more empathy for puppies and dogs than we do for adult human beings. Its why, ultimately, the term fur baby exists, even though I refrain from using it myself.

The next time I need to justify my intense affection for my dog, perhaps I should present my boyfriend with a study undertaken in 2015 at Azabu University in Japan. Takefumi Kikusui, from the Department of Animal Science and Biotechnology, got together with his colleagues to investigate why we are so close to our pets. He had been a dog owner for 15 years and, just like me, wondered at the intensity of the humandog bond. To find out more about what happens when we interact with our dogs, he invited 30 people to bring their dogs into the laboratory. He also took part, with his two standard poodles, Anita and Jasmine. For comparison, he invited a few people who had tried to domesticate wolves and he also invited their wolves.

Upon arrival, they were all humans, dogs and wolves asked to provide a urine sample. Researchers took away these urine samples for analysis, and then asked each person to play with their dog or wolf for 30 minutes. They hung out in a room with their beloved pups, most making eye contact with their pups for minutes at a time. The wolves, as you can imagine, didnt partake in a lot of loving eye contact. After half an hour, another urine sample was taken, which was then tested, looking for any spike in oxytocin levels compared with the first sample.

Next page