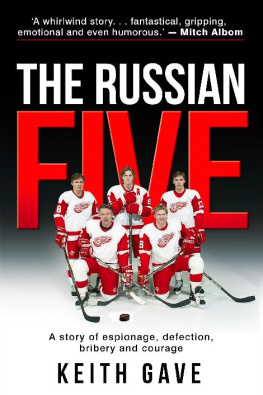

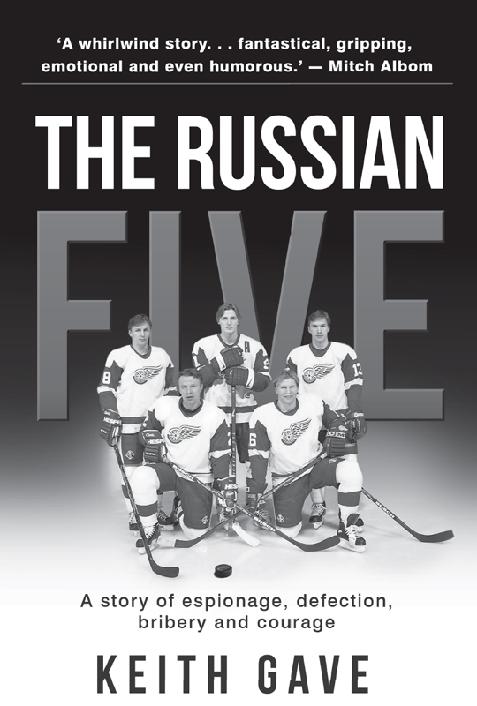

THE RUSSIAN

FIVE

KEITH GAVE

THE RUSSIAN FIVE

Copyright 2018 by Keith Gave and Gold Star Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author or publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960389

ISBN: 978-1-947165-17-5 (hardcover)

ISBN: 978-1-947165-44-1 (eBook)

Printed and published in the United States of America.

This book is available in quantity at special discounts for your group or organization. For further information, contact Gold Star Publishing at (734) 717-8600.

The Gold Star Publishing Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information, contact the publisher at (734) 717-8600.

Visit our website at: www.keithgave.com

Contact the author at:

Cover design: Amjad Shahzad

Interior design: reddovedesign.com

100 Phoenix Drive, Ste 300

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108

www.danmilstein.com/gold-star-publishing-

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Table of Contents

For Jo Ann

On a visit to Russia as a graduate student, American author Elif Batuman spent all four days of a conference at Yasnaya Polyana, the estate of literary master Leo Tolstoy, wearing the same clothing.

Aeroflot, the countrys state-run airline, had lost her luggage. Unable to purchase new clothing because the estate was far from any shopping centers, she phoned Aeroflot each morning to inquire about her suitcase.

Oh, its you, the clerk sighed. Yes, I have your request right here. Address: Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoys house. When we find the suitcase we will send it to you. In the meantime, are you familiar with our Russian phrase resignation of the soul?

This is the story of five men who refused to resign themselves to a life in a futile, sometimes brutal system and forever changed their sport, and our world.

PROLOGUE

That Night in Helsinki

I nside the raucous Detroit Red Wings dressing room the air was palpable, a curious concoction of mist from cheap champagne and a cloudy haze from several bootleg Cubans. The added scent of many freshly uncapped beers helped camouflage the ubiquitous odor of the sweat of several exhausted men celebrating like the champions they had become just moments before. They were joined by scores of family members, friends, reporters and an eclectic assortment of celebrities who always seem to find their way into once-in-a-lifetime events like these. Among them was Jeff Daniels, the Academy Award-nominee and Wings season-ticket holder. And Alto Reed, the sax player in Bob Segers Silver Bullet Band who occasionally performed the national anthem before games.

Piercing voices and riotous laughter ruptured 42 years of pent-up frustration. Finally, the Stanley Cup had found its way back to Detroit. Here was a moment to savor for everyone in this room and the tens of thousands still hanging around on the streets surrounding Joe Louis Arena on a sultry late-spring evening. Many of them had just witnessed the conclusion of a four-game sweep of the Philadelphia Flyers. Most fans had left the building, but refused to go home. Many more left their homes after watching this unforgettable moment in Detroit sports history on TV, wanting to be part of the excitement. They drove to the northern banks of the Detroit River to join in a spontaneous celebration that lasted until the wee hours of the morning.

Championship celebrations throughout professional sports were pretty much the same at least until they started to be choreographed for TV, with players donning goggles to avoid the sting from the inevitable champagne showers. So it was on that pre-goggles night of June 7, 1997, when I inched my way into the crowded Red Wings locker room. The first player I encountered was Vladimir Konstantinov, who for some reason was going the other way, toward the exit. He had taken his Wings jersey and skates off, along with his shoulder and elbow pads, but otherwise was dressed as he had been a few minutes earlier with his teammates, waltzing the Stanley Cup around the ice. His left hand gripped a bottle of bubbly along with an unlit cigar dangling precariously between his fingers. His right hand found mine through the crowd as soon as we made eye contact.

Here was a man as friendly and affable away from the ice as he was contemptible on it, now smiling wearily. At 30, he was in the prime of his career and one of the best defensemen in the world. And he played much, much bigger than his 5-foot-11, 180-pound frame. But the ferocity with which he played took a toll, and I understood at that moment why, even since his days as a teenager in junior hockey, teammates called him Dyadya Grandpa. Even then, he was 18 going on 40. After a brutal two-month stretch of Stanley Cup playoff hockey, he appeared as though he might be pushing 60 the way he moved.

Congratulations, Vladdie. Molodyets, I told him, using the Russian word loosely translated to mean attaboy.

Here was a man so colorful he needed more than one nickname. The Vladinator, fans loved to call him. But to his opponents whod encountered the blade of his stick along the boards, he was Vlad the Impaler. To most of those who played with him, though, he was simply Vladdie, the guy who always had their backs.

It was very hard, he said in barely a whisper, so hard. As he spoke, he pulled me toward him in a one-armed embrace, soaking me with a mix of suds and sweat from the blue undershirt he wore still tucked into his hockey pants. We win the Cup! We win! But it was so hard. Hardest thing ever.

As he spoke, he raised the bottle of champagne and poured the remnants over my head and laughed. Then he whispered the word spaciba.

Thank you, he said, repeating himself in English, looking at me in a way that made me wonder exactly what he meant.

Very slowly, I made my way around the room, shaking hands, asking a few questions, trying to take notes Id never be able to read because the ink on the paper became illegible as it continued to rain champagne and beer. There was Steve Yzerman, the team captain, shaking hands, surrounded by reporters and patiently answering nonstop questions after his long-awaited waltz around the rink with the Cup over his head. Never again would his leadership be questioned. Nearby were Slava Fetisov and Igor Larionov, two aging former Soviet Red Army stars who had just won the only prize that had eluded them in their redoubtable careers. Alongside Larionov was Slava Kozlov, who grew up a few blocks from Larionov in their hometown of Voskresensk nearly 5,000 miles to the east of Joe Louis Arena.

At various corners of the room, there were Kris Draper, Joey Kocur, Kirk Maltby and Darren McCarty, four-thirds of the Grind Line (the three-man forward unit the Wings deployed against the opposing teams top players) that meant so much to this team of superstars. And Nicklas Lidstrom, who would become known as The Perfect Human the way he conducted himself on and off the ice. I stopped to congratulate them all, finally making my way to a corner where the best hockey player in the world was surrounded by friends and family.