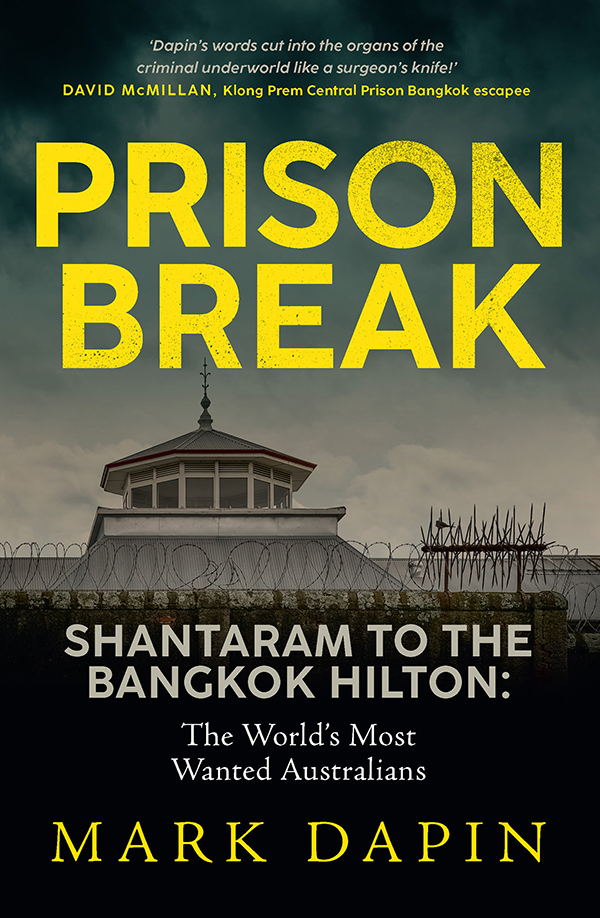

First published in 2021

Copyright Mark Dapin 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Every effort has been made to trace the holders of copyright material. If you have any information concerning copyright material in this book please contact the publishers at the address below.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76106 515 6

eISBN 978 1 76106 250 6

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

Cover photo: Anne Morley

Contents

White Australia was a nation built on the convicts back. The First Fleet of prison ships from England arrived in Botany Bay in New South Wales in 1788. The six convict transports among the eleven vessels carried about 750 sentenced prisoners, male and female, Christian and Jew. They had been sent to the ends of the Earth for punishment, rehabilitation, and to build a settlement that was mocked in London as a colony of thieves.

Until the invasion of Australia, the British government had sold unwanted convicts to ship-contractors, to be freighted to the Americas and trafficked to southern plantation owners. This trade had come to an end with US independence in 1776 and the unfortunates sentenced to transportation had been left rotting, and occasionally rioting, in prison hulks moored on the Thames and elsewhere.

The crimes of the early convicts included stealing a hairbrush, stealing a handkerchief and stealing bacon. Three men were transported for stealing their own toolboxes. About twenty men and women were dispatched to the colony for stealing a cap. But the majority of lawbreakers in the First Fleet were probably professional criminalsburglars, pickpockets and larcenistsand prostitutes, driven to crime by the miserable poverty of British slum life. They were accompanied and guarded by more than 200 Royal Marines. From the very beginning, white Australia was a society of prisoners and overseers, crims and screws.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, there was little point in trying to escape as there was nowhere much to go. Nonetheless, William Buckley, a former soldier who had been transported for fourteen years for receiving stolen cloth, fled to the bush around Port Phillip, Victoria, in December 1803. He joined the Aboriginal Wathaurong people, who initially believed him to be a spirit. In 1835, thirty-two years after his escape, Buckley arrived at a European camp wearing a possum-skin cloak around his shoulders and carrying a clutch of spears and a stick. At first, he stumbled to speak English and refused to leave the Wathaurong but in time he was granted a pardon and reabsorbed into white society as an interpreter with the Aboriginal people. His adventures led to the coining of the Australian phrase youve got Buckleys, meaning you have no chance, although Buckleys life story would seem to demonstrate that even the least likely scheme might succeed with luck.

In September 1822, Alexander Pearce, an Irish convict originally transported to Van Diemens Land for seven years for stealing six pairs of shoes, escaped Macquarie Harbour Penal Station on tiny Sarah Island with seven other men. They quickly ran out of food and began to eat each other. Pearce later confessed that the first man to die was attacked with an axe while he slept. We then dragged him to a distance, and cut off his clothes, and tore out his inside, and cut off his head, said Pearce. Two of the fugitives put his heart and liver on the fire and eat [sic] it before it was right warm, said Pearce. The next morning [the body] was cut up and divided, and each one got an equal share. Three more escapees died and were eaten before Pearce was taken back into custody and returned to Macquarie Harbour. One year later, Pearce escaped again, this time with twenty-one-year-old Thomas Cox, whom he promptly killed, chopped up, roasted and ate, then slipped a piece of the body into his pocket for later. This time, Pearce was not starving when he turned cannibal. It was said he was also carrying bread and either pork or cheese in his pocket.

Pearce was hanged on 19 July 1824.

The beloved Australian idea of building a supermax jail within a high-security prison had its first airing in Port Arthur, Tasmania. Here, south of almost everything in the known world, transportees who reoffended in Australia were sent to a severe industrial prison in a natural penitentiary that was linked to the mainlandwhich was itself an islandby an isthmus secured by soldiers, mantraps and vicious, hungry guard dogs. Nevertheless, Irish convict Martin Cash escaped with two other men in December 1842 and the three desperados corporatised as the Cash and Co. gang. Like so many future escapees, they turned to armed robbery. Cash became notorious in the colony as a bushranger (in England, he would have been called a highwayman; in the US, a stagecoach bandit) and eventually murdered a constable and was transported for life to Norfolk Island, about 1400 kilometres east of New South Wales. He was released in 1854 and died in bed.

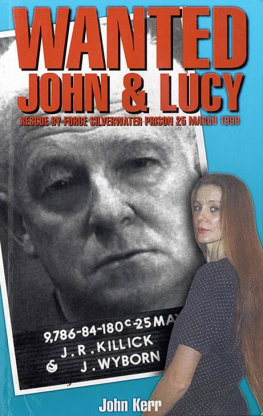

Prison escapessuccessful and otherwisehave been a feature of Australian history since Europeans first brought the idea of jails to the continent, and two modern Australian prison breaks are remembered all over the world. In July 1980, armed robber Gregory John Peter Smith rappelled down the front wall of Pentridge to begin a series of swashbuckling adventures that would eventually form the basis for his bestselling novel, Shantaram. In March 1999, armed robber John Killick was broken out of Silverwater prison by his Russian girlfriend, Lucy Dudko, who hijacked a helicopter to airlift Killick from the yard. Smith was twenty-eight years old when he escaped. Killick, incredibly, was fifty-seven.

Although Killick and Smith had served time in the same jailHMP Pentridge in Victoriatheir sentences did not coincide, and they never met. But the two men had much in common, from their easy charm and humour to their talents for armed robbery, from their crazy bravery to their striking looks, and from their battles with addiction to their literary ambitions.

Another Australian criminal, drug-trafficker David McMillan, made history and headlines in August 1996 when he became the first Westerner to escape from Thailands Klong Prem prison (the sardonically nicknamed Bangkok Hilton). McMillans story had curious parallels with Smiths and even offered a farcical prototype for Killicks when, in January 1983, McMillan became involved in an unlikely plan for a helicopter escape from Pentridge masterminded by a buttock-duelling bigamist and executed by a former soldier who was later to achieve fleeting fame as a kleptomaniac butler.