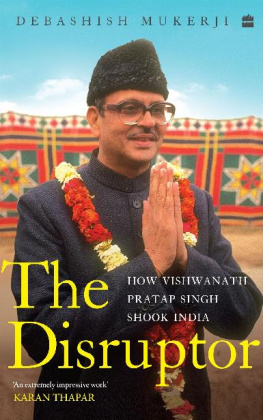

U nlike many others in his family, Vishwanath Pratap Singh had little faith in astrology or palmistry. His father and eldest brother were not only staunch believers but also practised both; V.P. Singh, however, claimed he was never curious about either. It was because I found that many predictions turn out wrong, he said. The wrong ones are never remembered, only the correct ones are!

It had indeed turned out that way. V.P. Singhs political career advanced at a blistering pace through the 1980s. He became Uttar Pradesh chief minister, Union commerce minister, Union finance minister, Union defence minister and finally Prime Ministerall in the space of a decade. Earlier, he had also been deputy ministerand subsequently minister of statefor commerce from October 1974 to March 1977. But his tenure in each of these offices was short. The first in the commerce ministry, at two years and five monthspromoted to minister of state for the last threeeventually proved to have been the longest.

His stint as UP chief minister lasted exactly two years, from June 1980 to June 1982. He was commerce minister for just a year and seven months, from January 1983 to August 1984. His high-profile finance ministry tenure under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi again ran for precisely two years, from January 1985 to January 1987, when he was moved to the defence ministry, from which he resigned in less than three months. Finally, his prime ministerial term, starting 2 December 1989, ended in only eleven months.

And yet, in each of his last three positionsas finance minister and defence minister in the Rajiv Gandhi-led Congress government, and Prime Minister in the subsequent Janata Dal governmentas well as in the two-and-a-half-year interval when he held no official position at all, some of V.P. Singhs actions changed the course of Indian political history.

The best-remembered of these actions is undoubtedly his introduction, as Prime Minister, of 27 per cent reservation in Central government services for the socially and educationally backward classes, or other backward classes (OBCs), identified on the basis of caste. The Indian Constitution, adopted in 1950, seeking to correct the inequalities in Hindu society created over millennia by its caste system, had provided reservations for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), but not for OBCs. V.P. Singhs announcement, on 7 August 1990, drawing on the recommendations in the report of the Second Backward Classes Commission, chaired by Bindeshwari Prasad Mandal, remains the single-biggest step towards affirmative action in the country thereafter.

At the time it proved hugely controversial, sparking a hysterical two-month-long protest by the upper and intermediate castes excluded from such reservation. This snowballed to a grisly apogee, when young people from these castes began setting themselves on fire, believing that their future employment prospects were doomedan apprehension that, once OBC reservations were formally adopted in 1993, was found to have been utterly misplaced. Apart from making access to Central government services easier for OBCswho were greatly underrepresented in them until thenand indeed introducing the term Mandalization into the nations lexicon as a general descriptor for the attenuation of elitism and consequent increase of egalitarianism in any context, the move also had tremendous political impact.

It accelerated the political consolidation of OBCs across north India, leading them to assert their collective strength in subsequent elections much more forcefully. Its most dramatic effect was seen in UP and Biharstrongholds of the Congress until then, but where the party drew most of its votes from upper castes, SCs and Muslims, having short-sightedly never courted the OBCs. In every Lok Sabha election until 1984 (barring the 1977 post-Emergency aberration, when it got no seats at all in either state), the combination the Congress had forged enabled it to win the bulk of seats in both states, which, in turn, contributed almost one-third to its nationwide tally, providing it comfortable majorities. The Congress also won most of the assembly elections in both states until 1985, with the same electoral combination.

But once the Mandal Commissions proposal had been introduced by V.P. Singh, the setback the Congress faced in the 1989 Lok Sabha pollsinitially thought to be temporary, like that of 1977turned out to be permanent. Barring one exception in 2009, the party never won more than 10 seats in UP and 5 in Bihar in subsequent general elections; it also never formed the government in either state again. From once being Congress bastions, UP and Bihar are now the partys main vulnerabilities. In the remaining north Indian states too, OBCs have affirmed their importance in elections and played a far greater role in shaping their politics than they did before V.P. Singhs decision.

Detractors of the step have termed it purely political, taken solely due to V.P. Singhs differences with his deputy prime minister, Devi Lal. They maintain that after V.P. Singh sacked Devi Lal from his cabinet and wanted thereafter to isolate him, he enforced the Mandal reports recommendation, thinking it would be the best way to prevent Devi Lals support group of members of Parliament (MPs) in the Janata Dal from continuing to back him. Undoubtedly, as some of his colleagues at the time have since testified, the timing and abruptness of V.P. Singhs announcement, barely a week after he fired Devi Lal, was dictated by such a strategy. It is another matter that the strategy failed and V.P. Singhs government fell three months later, in November 1990.

Yet, it is also clear, from a series of steps he took as soon as he became Prime Minister, well before his conflict with Devi Lal reached a flashpoint, that V.P. Singh always intended to adopt the Mandal reports main proposal. The announcement could never have been made without this earlier groundwork. Besides, actions have consequences irrespective of the motives prompting them, and the compulsions behind V.P. Singhs move in no way reduce its significance.

P.V. Narasimha Rao, who became Prime Minister in June 1991, and Manmohan Singh, his finance minister at the time, are rightly credited with ushering in Indias economic liberalization by dismantling the Licence Raj that had been built over the past four and a half decades. But they had a predecessor, who sought to move the economy in the same direction, yet who is rarely acknowledgedV.P. Singh.

V.P. Singhs first budget speech as finance minister on the evening of 16 March 1985 was a shocker for many of his listeners (although it had the full support of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi), as it substantially reduced both personal and corporate taxes, slashed import and excise duties, and eased considerably the expansion limits that had been imposed by earlier governments on most industrial houses (fearing the creation of monopolies). And while Indias dire economic situation in 1991 left the Narasimha RaoManmohan Singh duo little choice but to amend policies as they did, V.P. Singh took baby steps when there was no such imperative, having realized that the states heavy hand on the economy was choking growth.

But the blowback was so strong, not only from the Opposition parties but also from many Congress leaders (who termed it a total surrender to capitalism), that V.P. Singh was forced to revert to the old socialistic pattern in the following years budget. He tried again with the 1990 budget, alongside new industrial and agricultural policies the year he became Prime Minister, but the precarious nature of his coalition government, as well as opposition from within his own party, stymied his efforts.