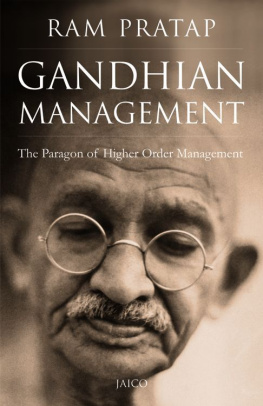

Pratap Bhanu Mehta - The Burden of Democracy

Here you can read online Pratap Bhanu Mehta - The Burden of Democracy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Penguin Random House India, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Burden of Democracy

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House India

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Burden of Democracy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Burden of Democracy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Burden of Democracy — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Burden of Democracy" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Pratap Bhanu Mehta is an Indian academic. He has been the president of the Centre for Policy Research and has taught at New York University, Harvard University and Jawaharlal Nehru University. Since July 2017, he is the vice chancellor of Ashoka University. His areas of research include political theory, constitutional law, society and politics in India, governance and political economy, and international affairs. Mehta has served on many central government committees, including Indias National Security Advisory Board, the Prime Minister of Indias National Knowledge Commission, and a Supreme Courtappointed committee on elections in Indian universities. He received the 2010 Malcom S. Adisheshiah Award and the 2011 Infosys Prize for Social Sciences.

Its better...

To honour Equality who ties friends to

friends, cities to cities, allies to allies.

For equality is stable among men.

If not the lesser hates the greater force,

And so begins the day of enmity.

Equality set up mens weights and

measures, Gave them their numbers.

Euripides, The Phoenician Women

The creation of India as a sovereign independent republic was, in some profound sense, the commencement of a bold experiment in political affairs as significant as any that had been conducted in history. To give 200 million largely unlettered and unpropertied people the right to choose their own government, and the attendant freedoms that come with it, was a leap of faith for which there was no precedent in human history. Certainly, no body of European social thinking at the time, on the prospects of democracy, would have counselled such a course; there was no instance from the past that could be the basis for confidence that this experiment would work. No political formation that could provide an instructive example of how to make democracy work in such seemingly unpropitious circumstances: unbounded poverty, illiteracy, the absence of a middle class and immense and deeply entrenched social cleavages. Indeed, if history and social theory were taken to be any guide, the presumption would have been quite the reverse. Democracy in India is a phenomenon that, by most accounts, should not have existed, flourished or, indeed, long endured.

What does democracy mean in this setting apart from its obvious reference to practices of popular authorization? Can one fix the meaning of democracy, the hopes and aspirations it generated, in a setting as socially diverse as Indias? Democracy would mean hope; it would establish the principle of political equality, freedom and dignity indelibly in Indian society. But what concrete sense of empowerment and opportunity would it bring to bonded labour, landless peasantry, deprived untouchables? Could they share the same expectations from democracy, and all the liberal freedoms that came with it as, say, their middle-class lawyer counterparts who drew up the Constitution? Despite some limited experience with self-government, there was no way knowing what possessing the right to vote meant, or how indeed it would be exercised. For some, democracy would appear to mean the freedom to rediscover and assert their tradition, for others, protection from it. What new forms of collective mobilization would democracy bring about and what ends would these serve? The kaleidoscope of meanings, expectations and hopes that different sections of Indian society placed on democracy, the various ways in which they contextualized it, would render any attempt to fix its meaning and scope futile. The symbols of a new awakening India, the flag, the ubiquitous presence of Nehruin whose own figure most expected the contradictions of India to resolve themselves, the Congress partythat had for the most part and brilliantly engineered a multi-class, multiregional alliance, all symbolized immense hope, but one whose contents remained undefined and contested. Many groups would try to redeem the promissory note that the republican constitution promised in their own distinctive and often conflictual ways. The protean character and meaning of Indias democracy would occasion the remark that the point of democracy is to be forever a contest over its own meaning.

The significance of Indias democratic experiment was itself disguised by the historical process through which it came about. While there was a good deal of consensus, even as early as the beginning of the twentieth century, that the people would in some senses be authoritative, there was also a lot of confusion over what exact form the deference to popular sovereignty would take. As it happened, representative institutions slowly took shape as an outcome of the nationalist movements struggle against the colonial powers. The early experiments in representative government were limited both by the extent of suffrage and the scope of the powers allotted to those governments that worked under them. But representative government came to be characterized as simply the outcome of a negotiation between Indias elites on the one hand, and colonial powers on the other. Democracy, on this view, was not the object of ideological passion, it was not born of a deep sense of conviction widely shared, but it was simply the contingent outcome of the conflicts amongst Indias different elites, or an unintended by-product of the British having produced too many lawyers adept in the idioms of modern politics. There was no grand design in Indian democracy, and hence nothing to memorialize in the way the American and French revolutions did their democratic transitions.

Secondly, there was the obvious fact that nationalism, rather than democracy, seemed to be a more primary political passion. While the two are by no means incompatible, it was unclear to many whether the great churning the nationalist movement had produced was sustained by the primacy of the nation or a love of democracy. The celebration of a nation that had ostensibly existed since time immemorial seems to disguise the fact that something radically new was happening. The nation seemed to then, as it often does now, cast a shadow over the democracy that ought to define it, and the trauma of Partition seemed to make the momentous deliberations of the Constituent Assembly appear trite.

The invention of republican citizenship in India was indeed a historic event, and a rupture with the past. While many had hoped that the new constitution would simply be encased within the supposed historical identity of India, its diverse and complex cultural sympathies, few imagined that the opportunities it afforded would intensely politicize all areas of organized collective existence in India. The resources of history and culture, rather than providing comfort and continuity, would themselves be the first categories to be subject to intense political scrutiny. The nationalist movement had attempted the delicate task of making India transcend its own traditions without making tradition itself despicable; to repose a faith in an Indian identity that could survive the contested character of its political expressions. But in the end, democratic politics was the space where the place of tradition and the question of identity alike would be reopened.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Burden of Democracy»

Look at similar books to The Burden of Democracy. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Burden of Democracy and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.