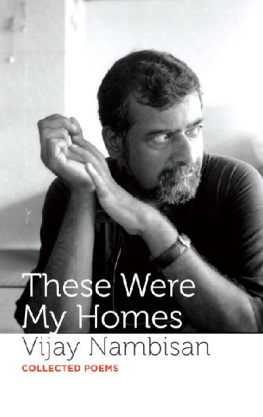

These Were My Homes

PRAISE FOR VIJAY NAMBISAN

Hell, or a state very much like it, does feature in Nambisans poetic underworld, which is deep, intricate and enticing. But its attendant horrors are never indulged in for their own sake and are kept well in check by a certain wit, a muscularity of mind, which remind me of a similar grace in poets as far distant in time from each other as Robert Graves and John Donne.

Adil Jussawalla

Nambisans view of humankind is bleak, his view of the possibilities of poetry even bleaker. The Gods are lonely and turned away by the mobs...at every border, and no amount of poetry can breathe life into a dying city. We have art so that we may not perish by the truth, Nietzsche says, and Nambisans art is of the highest order, a reminder of what English-language poetry in India can do when the language is handled with skill and passion by someone who is so clearly in love with it, in all its moods, from sombre to playful, from dark to light. This love is on display in every page of First Infinities , whose every line is worthy of his great precursorsArun and Dom and Nissimwhom Nambisan so lovingly invokes in the books opening poem.

Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

Vijay Nambisans sensuous, intelligent, and often unsettling poems are parables for the time we live in now, without in any way being portentous or just topical. Nambisan appears to achieve his mix of reporters sense of being present at an important event of moment with the artists refracted relationship with meaning through his preoccupation with formal design and mythic allusion. In poems such as Millenium, whose There was not much light in the world when we left reworks Nissim Ezekiels Enterprise (It started as a pilgrimage), Nambisan, half a century later, seems to extend and interrogate, while doggedly continuing with, the curious business of Indian poetry in English itself.

Amit Chaudhuri

Contents

Introduction

The very first poem in this volume is The Miracle of the Pomegranate. In the August rain, it says, the flowers are changing / The shape of the tree. Exactly twenty-five years after the publication of this poem in 1992, Vijay Nambisan passed away in August, raising once again that unanswerable but always haunting question about the relationship between poetry and prophesy.

What does a poet see that others cannot? In Vijays intelligent, self-aware meditations on mortality and human folly in this final and complete volume of his poems, readers will come to as close an apprehension of the nature of epiphany as is possibleto those sudden illuminations of the spirit that can, without warning, light up flares in our dull, corporeal bodies. In Vijays words, some stoves are born to make trouble / But this one clicks sweetly into flame. Poetry is that space where words click, sometimes miraculously, into flame. Vijay knew this space most intimately; he was as familiar with it as the process of making coffee.

I measure decoction into a cup,

Add milk and water, pour the whole into

A suitable cauldron, and place it

On the stove...

There is something in the making of coffee

That dulls the moral sense.

I spoon in sugar

And sip that first sip against which it is vain

To argue.

Not strong enough.

I must add

Some instant powder, which I loathe, or spoon in

Some more decoction, which will make it cold.

This is not how the masters advocate

The making of coffee, but I have succeeded

In taking seven thinking minutes off my life.

Is this not an almost perfect description, impressively deadpan, of the process of producing that verbal decoction we call poetry? Further, in its implicit rejection of any predictable mastery over the process, its meditation on the moral sense, its Zen-like suggestion that the purpose of life is to bypass the toils of thought, is it not also akin to something like the prophets vision?

The word prophesy came into English from the Greek in the usual complicated fashion via Latin and French. A prophet was one who had the gift of interpreting the will of the gods. True, it does appear improbable that Vijay would tamely agree on his elevation to prophetic status in the originary, old-fashioned sense of this 14th-century English word. Afterall, the 111 poems in this slender volume written over his brief lifetime lay no claim to a superior connection with any gods or demons. They display, instead, a keen understanding of science and its uncompromising rationality (radium decays a little bit at a time), of the temporary bonds of love and desire, of waddling ducks and arching cats, of the particular genealogies of speech that Vijay came to inherit through his father, his grandparents, his mother and aunts, and of the questing history of our bipedal species (Diary of the Expedition). This seems a set of concerns robustly tied to experiences of the then, here and now. Science, genealogy, observations of nature and animals, a record of passing moments of human contact, marked sometimes by playfulness but never by solemnity. Exactly where in these familiar themes lies the space for prophesy, that leaping desire to express the will of divinity? By what miracle does it happen?

Fine poetry, though, does not yield up its secrets easily. We find our first clue to Vijays gift of looking into the heart of things, his seers vision, in the recurrent themes of his poems (The Deserted Temple, Christ Stopped Here, Good Friday) and in his obsessive rendering of mythological themes (Aswatthama, Chyavana, The Lord of the Dance). In Holy, Holy, he speaks of rain that threatens this ordinary day / With magic.

Things that grow manifest,

Plainly, the unnatural: more sure

And permanent is the unwalked way,

Lifeless air, stone unencumbered

With feelings; not obsessed, therefore pure.

This talk of the unwalked way glimpsed in rain-washed purity, of a world unsullied by human feeling, is not unrelated to saintly yearnings. Like so many of us today, Vijay confesses to being Born without a language and in the frightened iconoclasm of my age...I have burdened words with a soul whose sins are my own. The prophets business is to attend keenly to the voices that will lead us out of the wilderness of human suffering. It is exactly such an awareness of the high stakes involved that Vijay evinces in a poem like Narcissus in the Drought.

The stream sounds in my ears,

with a voice both clear and hoarse.

There is flood in the air; in the mouth, great thirst,

A prayer to the shadow to move a little more

Towards a vision I know possessed me there before.

And then, at the end of this same poem, there is that clear-eyed, startling turn to personal extinction that seals the prophets own fate, as Vijay declares without sentiment:

I cannot hope to live now; but first

It must hurt somewhat, to perish, not knowing why.

Poets like Vijay see as distinctly as any prophet what he calls The Hole in the Earth, the bog beneath our feet into which anyone of us can sink. It is this unusual prophetic quality that makes his voice so valuable in our godless, techie times when each of us so easily has the chance to be a (false?) prophet on airy social media, to trade glibly in infinite futures. We must not forget, either, that the one book that Vijay ever translated was called Puntanam and Melpattur: Two Measures of Bhakti (2009), and there is little doubt that a kind of modernist bhakti permeates Vijays work when read in its entirety, even if it is not exactly a sanitized version of the emotion. There is a hole, he writes, through to the earths bowels.