PRAISE FOR MARY ROACH

I sometimes wonder what animals have done wrong to deserve humans and what we do to them. But I know that humanity has done something right to deserve Mary Roach, the best guide possible to the fascinating but sometimes fraught interactions between human, animal and nature. She prowls through this intersection of worlds with the sleek grace of a leopard, diving into garbage cans, Indian elephant politics and mass murders of murders of crows, with her usual wit and wisdom.Theres only one downside to this delightful and brilliant book, and thats that the animals cant read it too.

Rose George, journalist and author of Nine Pints

As hilarious as it is thoughtprovoking, Animal Vegetable Criminal is a brilliant read. Only Mary Roach can make such an obscure subject so intriguing. From battles with birds to marauding macaques, Roach reveals what happens when nature breaks human laws, with fascinating results.

Monty Lyman, author of The Remarkable Life of the Skin

Mary Roach has been writing brilliant, funny and illuminating popular science books for years. Unfortunately at least for those of us with ambitions to step into her shoes she has gone and done it again! Animal Vegetable Criminal is as good as anything this wonderful author has ever written, and that is saying something.

Graham Lawton, author of Mustnt Grumble

Roach [is] a gentle, highly original and exceptionally funny science writer Grunt is an extraordinary piece of reporting alive with stories and gobbets of trivia, many of them told for the first time.

The Times on Grunt

[A] quickfire exploration of the extraordinary world of military science.

Sunday Express on Grunt

Sometimes you simply have to marvel at her ability to get behind the press release and into the laboratory Completely fascinating.

Daily Mail on Grunt

[A] splendid study of all things alimentary

Bill Bryson on Gulp

The funniest book [of the year] by far almost every page made me laugh out loud.

Sunday Times on Gulp

Insightful, sharp science writing that will have you snorting with laughter is Mary Roachs speciality.

New Scientist on Gulp

Dont miss thisouting into space where no one can hear you scream with laughter As a science writer Roach is seriously funny. She asks the right questions and provides answers like the best deadpan stand-up comic.

The Times on Packing for Mars

Even readers with a long-term interest in manned exploration should find some new information withinif you like your space science served with emotion, anecdotes, and excreta, this is for you.

BBC Sky at Night on Packing for Mars

This is definitely the kind of book thatll have you reading out the juicy bits to friends and familylike a sassier i.e. ruder Bill Bryson Fascinating.

Daily Mail on Packing for Mars

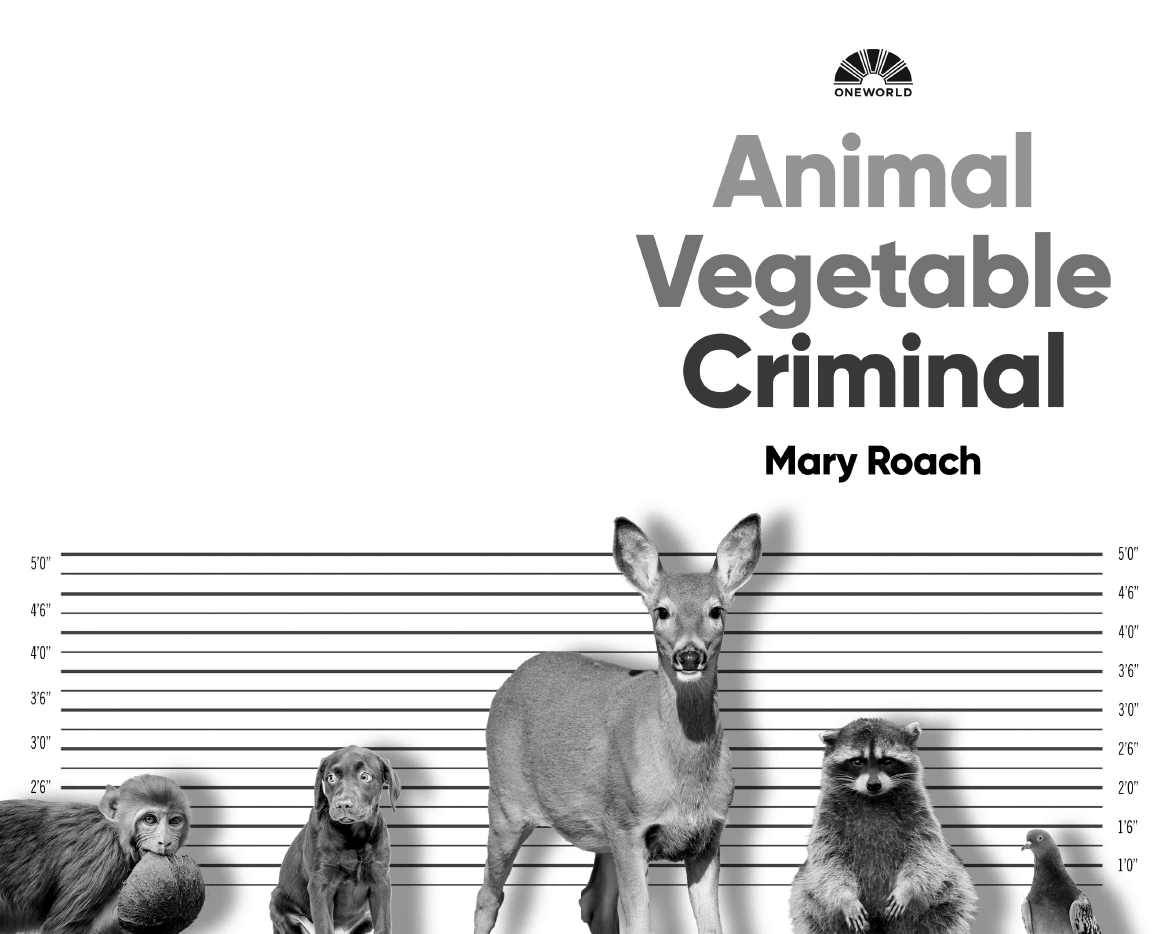

ALSO BY MARY ROACH

Grunt: The Curious Science of Humans at War

Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal

Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void

Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex

Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers

For Gus, Bean, and Winnie. To the farthest star.

Contents

A Quick Word of Introduction

On June 26, 1659, a representative from five towns in a province of northern Italy initiated legal proceedings against caterpillars. The local specimens, went the complaint, were trespassing and pilfering from peoples gardens and orchards. A summons was issued and five copies made and nailed to trees in forests adjacent to each town. The caterpillars were ordered to appear in court on the twenty-eighth of June, at a specified hour, where they would be assigned legal representation.

Of course no caterpillars appeared at the appointed time, but the case went forward anyway. In a surviving document, the court recognizes the rights of caterpillars to live freely and happily, pro- vided this does not impair the happiness of man... The judge decreed that the caterpillars be assigned a plot of alternate land for their sustenance and enjoyment. By the time the details were worked out, the defendants, having pupated, were surely through with their devastations, and all parties no doubt left the proceed- ings satisfied.

The case is detailed in an unusual 1906 book, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals. When I first paged through it, I wondered if it might be an ambitious hoax. Here were bears formally excommunicated from the Church. Slugs given three warnings to stop nettling farmers, under penalty of smiting. But the author, a respected historian and linguist, quickly wore me down with a depth of detail gleaned from origi- nal documents, nineteen of which are reproduced in their original languages in a series of appendices. We have the itemized expense report of a French bailiff, submitted in 1403 following the murder trial of a pig (cost of keeping her in jail, six sols parisis). We have writs of ejectment issued to rats and thrust into their burrows. From a 1545 complaint brought by vintners against a species of greenish weevil, we have not only the names of the lawyers but early examples of that time-honored legal tactic, the stall. As far as I could tell, the proceedings dragged on eight or nine monthsin any case, longer than the life span of a weevil.

I present all this not as evidence of the silliness of bygone legal systems but as evidence of the intractable nature of human- wildlife conflictas it is known today by those who grapple with it professionally. The question has defied satisfactory resolution for centuries: What is the proper course when nature breaks laws intended for people?

The actions of the magistrates and prelates made no rational sense, of course, for rats and weevils cannot understand property law or be expected to conform to the moral principles of human civilizations. The aim was to cow and impress the populace: look here, even nature must bend to our rule! And it was, in its way, impres- sive. The sixteenth-century judge who granted leniency to moles with young offspring made a show not only of his authority but of his temperance and compassion.

Wandering through the Middle Ages and the centuries just beyond, I began to wonder what the modern epoch had brought to bear on these matters. Having sampled the esoteric solutions of law and religion, I set out to see what science has been bring- ing to the table, and what answers it might offer for the future. So began more wandering. My guides were people with titles unfa- miliar to me: Human-Elephant Conflict Specialist, Bear Manager, Danger-Tree Faller-Blaster. I spent time with predator attack spe- cialists and attack forensics investigators, builders of laser scare- crows and testers of kinder poisons. I traveled to some of the hot spotsback alleys in Aspen, Colorado; leopard-terrorized ham- lets in the Indian Himalaya; St. Peters Square the night before the popes Easter Mass. I considered the contributions of bygone professionalsthe economic ornithologists and the rat searchers as well as the stewards of the future, the conservation geneticists. I taste-tested rat bait. I was mugged by a macaque.

The book is far from comprehensive. Two thousand species in two hundred countries regularly commit acts that put them at odds with humans. Each conflict needs a resolution unique to the setting, the species, the stakes, the stakeholders. What you have here is the highlights of a two-year exploration, a journey through a world I had not known existed.

Next page