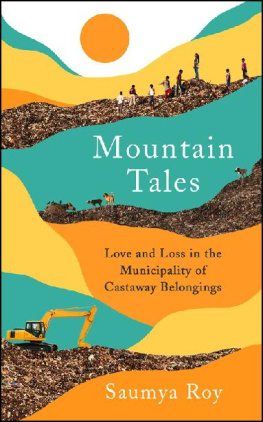

MOUNTAIN TALES

MOUNTAIN TALES

Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings

SAUMYA ROY

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

Profile Books Ltd

29 Cloth Fair

London

ECIA 7JQ

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Saumya Roy, 2021

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Berling Nova Text by MacGuru Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78816 536 5

eISBN 978 1 78283 710 7

My grandmother, professor and poet, who wrote

have you seen, my friend? on the peaks of inky, dark, rain cloud-topped mountains, snowy white illuminating clouds appear sometimes?

and Prashant Kant, my uncle, who could not see but showed me how to spot the illuminating clouds.

For illustrative purposes only

Cast of Principal Characters

At the Mountains

Hyder Ali Shaikh : Waste-picker at the Deonar garbage mountains; father of Farzana and her eight siblings

Shakimun Ali Shaikh : Hyder Alis wife; mother of Farzana and her siblings

Jehana Shaikh : The oldest of the nine children

Jehangir Shaikh : Hyder Alis oldest son and the second oldest of the children

Rakila Shaikh : Jehangirs wife, and mother of their three children

Alamgir Shaikh : Hyder Alis second oldest son, who drives garbage trucks

Yasmeen Shaikh : Alamgirs wife and mother of their two children

Sahani Shaikh : The second oldest of the Shaikh daughters

Ismail Shaikh : Sahanis husband, who does odd jobs around the mountains

Afsana Shaikh : The third-oldest sister, and the only one to have left the mountains. A seamstress and mother of two

Farzana Shaikh : Hyder Ali and Shakimuns fourth daughter, and the sixth of the nine children

Farha Shaikh : The sister who comes after Farzana; the two often pick together

Jannat Shaikh : The youngest of the daughters

Ramzan Shaikh : The youngest of the siblings, a son

Badre Alam : Hyder Alis cousin. He lives in the loft of the Alis home

Moharram Ali Siddique : A waste-picker known for working night shifts and finding treasures in mountain trash

Yasmin Siddique : Moharram Alis wife, and mother of their five children

Hera Siddique : Moharram Alis oldest child; one of the few girls from the lanes to have made it to high school

Sharib Siddique : The older of Moharram Alis two sons; he often misses school to pick on the mountains

Sameer Siddique : The younger of Moharram Alis sons

Mehrun Siddique : Moharram Ali and Yasmins middle daughter

Ashra Siddique : the youngest of the Siddique children

Salma Shaikh : A waste-picker; she arrived at the mountains with her two children more than three decades ago

Aslam Shaikh : Salmas older son, married to Shiva; the father of four sons and a daughter

Arif Shaikh : One of Aslams four sons

Vitabai Kamble : Said to be one of the oldest waste-pickers on the mountains; she came to live at the mountains rim in the mid-seventies with her husband and children

Nagesh Kamble : Vitabais oldest son; he came to pick at the mountains as a ten-year-old

Babita Kamble : Vitabais daughter

Rafique Khan : A garbage trader who also runs garbage trucks

Atique Khan : Rafiques younger brother, also a trader

In the Court

Dr Sandip Rane : A doctor who lives in a genteel neighbourhood near the mountains rim. In 2008 he had filed a contempt case against the municipality for failing to close the mountains down

Justice Dhananjaya Chandrachud : The judge who adjudicated on Dr Ranes case in the Bombay High Court

Raj Kumar Sharma : A local resident who grew up in a leafy area not far from the mountains; he filed a court case in December 2015 asking for the mountains to be mended

Justice Abhay Oka : The judge presiding for several years over the court cases regarding Deonar

Introduction

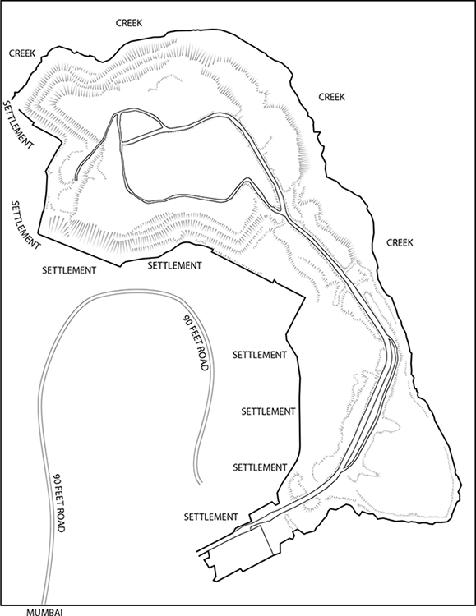

I first met the waste-pickers of Deonar in the summer of 2013, when they began coming to the office of the micro-finance non-profit I ran in Mumbai, looking for small, low-interest loans. They worked on the garbage mountains at the edge of the city, collecting trash to resell, they told me. I followed them back there, partly to find out what they did with their loans, but also to see this strange place, which I had heard of but, like most Mumbaikars, had never seen. I found a vast township of trash growing invisibly in plain sight mountains that were more than 120 feet high, surrounded on one side by the Arabian Sea and on the other by a sequence of settlements strung along it.

Thus began my more than eight years long entanglement with the Deonar mountains and their denizens. I watched the lives and businesses of four families unfold in their shadow. Most of all I watched a teenager, Farzana Ali Shaikh, grow into a life that seemed as unlikely as the mountains, rising precipitously with the desires that had flickered and died in the city. This book is Farzanas story, her familys and her neighbours story, and I am grateful for their permission to write about it.

I came to view the mountains as the pickers did: bringing the citys used luck, depositing its fading wealth in their hands. I attended hundreds of hours of court proceedings that aimed to control the citys waste, thinking every time that the mountains were about to move. I collected archival documents to unravel the rumours I heard. Kachra train ni yaycha , a picker had told me in one of my earlier walks on the mountains. Garbage once came here by train. It felt unreal, like many of the legends and lives around the slopes: a train service just for garbage? And yet it was true; years later I found myself at Oxford Universitys storied Bodleian Library, reading colonial records of how Bombays garbage had indeed come to Deonar by train.

Deonars mountainous township of trash created a world uniquely its own. And yet, wherever I went in the world, the pull of aspiration was just as unyielding, and as transient, throwing up waste mountains much like Deonar. A journalist friend had written of the waste Everest outside Moscow. The mountains in Delhi were said to be nearly as tall as the Taj Mahal and had tumbled down in avalanches, as had others in Colombo, Addis Ababa and Shenzhen, killing people while I researched Deonars more stable ones. One of the great urban legends of New York, I heard, was about the barge that floated off its coast, filled with the citys trash, with no state willing to accept it for burial. Then I met the former city official who had cut short a holiday to land the barge back in the city, the trash ending up at its own garbage mountains.

My years of walking the mountains showed me that, unlikely as the stories that emerged from Deonars township of trash felt, most of them were real. Parts of them unfolded in one way or another in most cities. Waste masses even float in the sea, making islands. I came to see these mountains as an outpouring of our modern lives of the endless chase for our desire to fill us with stuff. Our pursuit only lengthened these mountains, providing the raw material on which the waste-pickers built their lives, and left us unsated, searching for more, unseeing the world that our castaway possessions made.