contents

home weather

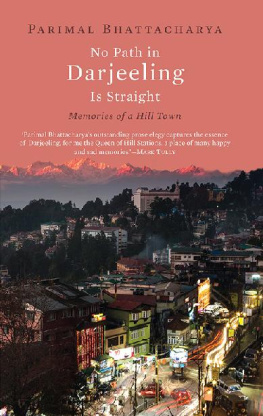

W hen the summer holidays come to an end, and the tourists make a beeline for the plains, that is when Darjeeling beckons me. July is the cruellest month here, July and August. The loneliest too. Weeks before the rains begin, as the heat begins to rise in the valleys, puffs of fog climb up the ravines and gorges to blot out the picturesque views until they are stretched out over the hill station like a grey dust cover. A dust cover for a toy town, packed and put away on the mountain shelf after the visitors have left, to be unwrapped again during the festival holidays in autumn. Until then, Darjeeling remains shrouded in fog, the tourist taxis with Sight Seen painted on them are put under covers at Singmari, the canary-yellow cable cars are sent away to their hangars at North Point, the Tibetan stalls below the Mall fold up, the lodges and holiday homes are closed for the season, the Bengalis who work there return to their homes in southern Bengal, the porters at the bus-stand return to their villages in Nepal, the Bihari shopkeepers return to their mulq. In the Gangetic plains of North India, it is the season of paddy-planting in rain-soaked fields. Not a sign of life is to be seen in the tea gardens after the second flush is plucked; even the livestock are herded away to higher altitudes to protect them from leeches. Rain falls endlessly through the day, the face of the sun cannot be seen for weeks and months. July is the loneliest month in Darjeeling, July and August.

The cruellest too. Endless rains seep into the cracks of brittle metamorphic rocks, seek out fissures, the ducts of dead roots, wash away the soil, and then, one fell moment in the dead of night, trigger a landslip that sucks in its wake buildings, roadways, trees, electric poles and sleeping humans. Darjeelingeys wake up on a grey, silent morning to discover that the scattering of huts on a hill slope that had stood there for so long is no more. Pieces of tin and wood are strewn a few hundred feet below amid a rubble of wet earth and stones. Limp, dirt-coated bodies are extracted out of it, bodies whose skins have turned blue and crinkled like paper. The survivors are given shelter in school buildings or in tents. In a few days, the remains of homes are picked up from the debris and the settlement rises again on another side of the hill. Old dovecotes and gate posts still stand upon the brown gash in the hillside, and perhaps a tin signboard that proclaims:

gurung nivas

be were of dog

Wild creepers cover the muddy scar faster than the tears can dry up. Nature is fecund in the season of rains here; she takes life with one hand and gives back with the other in various forms.

Water is the other name of that life. Since the end of winter, Darjeeling pines after water like a frantic swallow circling the parched sky for a drop of rain. In March the mountains turn a resplendent green, rhododendrons and magnolias bloom against blue skies, scented breezes ruffle the pine leaves, even the Kanchenjunga glows in the horizon all day long. Amid such a profusion of beauty, the townspeople are assailed by that most basic want: water. The municipal supply dribbles from the taps for a few hours every two or three days, unending queues of jerry-cans are seen day and night in front of the few trickling natural springs in town, pushcarts loaded with jerry-cans rush to far-flung neighbourhoods.

Fogs appear with the onset of summer, coils of vapour rise from the hot plains, the springs around Senchal Lake soak them up and slowly come back to life. But then, during this time of the year, tourists arrive in droves, Darjeelings population shoots up many-fold and the scarcity of water doesnt abate. This vital want at the centre of daily life rankles, suspicion lurks in the corner of the mind, ears remain pricked up for the faintest murmur of water. Incidents of theft occur from municipal-supply lines, from private tanks; brawls erupt at public springs.

This continues for weeks until the rains return, until water flows again in parched springs, from artesian wells, from household taps. The gurgle of water swelling in the empty pot rises from a low bass to a rich treble and then brims over with a flourish. For the people of Darjeeling, this is the most enchanting music in the world.

~

However, these are outward features. The inner truth is, it is in the season of rains that Darjeeling returns to itself. Day in, day out, it continues to drizzle through murky fog, turning everything wet and dripping, and casting a film of moisture over every object inside shuttered rooms. The Englishmen lovingly called this home weather. Viceroy Lord Lytton wrote to his wife in a letter: the afternoon was rainy and the road muddy, but such beautiful English rain, such delicious English mud!

But for the people from the dry sunny plains of India, it calls up a strange melancholy. A dull grey light from morning till afternoon disarranges the different hours of the day, strange mushrooms of memory and desire grow in the dishevelled depths of the mind, depression sets in. To these are sometimes added arthritic pains in the joints from old, forgotten injuries.

To battle the depression and pains is often more difficult than even facing the privations of daily life. Some give up midway. On 10 July 2008, a news item appeared in The Telegraph published from Kolkata:

Darjeeling, July 9: A merchant navy officer from Amritsar was found dead in a hotel room in Darjeeling this morning with police claiming to have found a bottle of aluminium sulphide and a suicide note written in Hindi from his bedside.

Nardev Singh Mehra, 44, had been staying at the hotel on Robertson Road since June 29, paying Rs 250 a day.

He used to bring food from outside and visited Mahakal Mandir, Japanese temple and Eden Dham in town. He used to say that he was writing about the history of Darjeeling, said Bipen Sharma, the manager of the hotel.

In the hotel register, Mehra had said he was from the merchant navy and had given his address as House No. 609/279, Royal Ludhiana, 1140001, Amritsar, Punjab.

The police also recovered a Continuous Discharge Certificate Cum-Seafarers Identity Document, issued in Mumbai in 1993, which says Mehra was the son of Mohinder Singh.

Last night, hotel employees saw Mehra laughing as he watched [a] cartoon on the TV set in his room. He usually woke up between 6 am and 7 am. But today, he did not wake up till 10 am, despite us banging on the door and sprinkling water through the ventilator. That is when we called the police, said the hotel manager.

The police broke open the door and found Mehra dead in his bed. We also found a bottle with aluminium sulphide written on it, along with packed food and a few banana skins, said a police officer. This looks like a suicide. We are trying to get in touch with the police in Punjab. No contact number is available as he had no mobile phone.

The police also claimed to have found a suicide note in Hindi. The note says he had been happy with his life and that no one was to be blamed for his death. It was pretty poetic, the officer said.

It is always difficult to get to the bottom of an act like this. But there have been similar incidents in Darjeeling, and perhaps it is no coincidence that many of them have occurred during the rainy months. Ten days after the suicide of the merchant navy officer, on 21 July, a thirty-three-year-old Swedish social worker named Isaac Homgren hanged himself in an apartment on Zakir Hussain Road. He had taken the two-room flat owned by a Sherpa on rent. He had come here for meditation, the landlady told the police. Three suicide notes were found in his room: one addressed to his parents, another to his landlord, and a third one to the government of India. It turned out that his travel visa had expired.