To Tod Nelson, for years of friendship and reading early drafts

Contents

The rows of ceiling fans struggled to cool the raked Kolkata auction room. Their collective whir barely covered the cawing of large crows on the trees outside or the incessant honking horns from black-and-canary-yellow Ambassador taxis moving through the perpetually slow traffic. Nearly two inches of rain had fallen on Friday, and after a relatively dry weekend, drenching monsoon showers returned on Monday, July 14, 2003. It was approaching ninety degrees Fahrenheit, and the humidity stood at over 90 percent. Parts of the city remained submerged knee-deep in water. Dark, spongy clouds hung overhead. Only the lightest of breezes moved in the thick air.

Tea buyers, agents, exporters, blenders, and packeteers had gathered for Sale No. 28 of Darjeeling tea on the second floor of Nilhat House, a boxy and bright midcentury midrise shoehorned into the old city center. The building houses J. Thomas & Co., Indias oldest and largest firm of tea brokers and auctioneers.

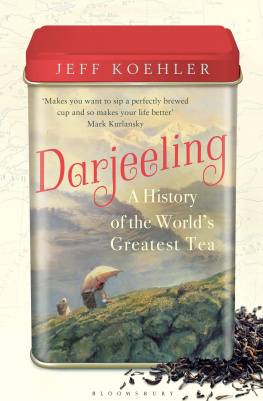

Darjeeling is known for its single-estate teas, unblended and unflavored. With characteristic brightness frequently likened to newly minted coins, fragrant aromas, and sophisticated, complex flavorsdelicate, even flowery (more stem than petal, as one expert blender put it), with hints of apricots and peaches, muscat grapes, and toasty nutsits the worlds premium tea, the champagne of tea.

That day at the weekly event, the auctioneer Kavi Seth thought they might see unusually high prices with the exceptional quality of some of the tea on offerspecifically a lot from Makaibari, one of Darjeelings oldest gardens. Since the early 1980s, Makaibari had been under control of Rajah

Seth started with J. Thomas in 1985, had been intimately involved with Darjeeling tea for a decade, and had been in charge of the catalog and auction of Darjeeling teas for the previous two years. While he had tasted tens of thousands of Darjeeling teas, Seth recognized something extraordinary in the Makaibari lot. A decade later he still vividly recalls its special flavor and quality. Seth did two things to build excitement. First, he spread the word among buyers. Second, quite extraordinarily, he listed it last in the catalog. Normally the standout teas are toward the beginning and then mixed around. But this would be the days final lot and force buyers to stick around until the very end.

In the crowded auction room, Seth worked through hundreds of lots of teas, coming, at last, in late afternoon, to the anticipated Makaibari offering.

That midsummer, Darjeeling tea was fetching on average 150.25 rupees per kilo, then worth about $3.25, at the weekly auction, with leaf gradesthe highest levelaveraging Rs 295.

Yet Seth opened the bidding at Rs 3,000.

Buyers, perhaps drained from the anticipation and tension, the warm room, and humidity outside, and keenly aware of the significant amount of money they were committing to laying out, slowly countered one another with slightly higher offers under the auctioneers nudging.

Then a new buyer jumped into the bidding. Representing a European firm, he was keen to secure the lot of five small chests of tea. A current surged through the room, and bidding rallied.

Sitting at a dais in the front of the room, the auctioneer took offers and counteroffers as the amount spiraled aggressively upward by the hundreds of rupees, speeding past Rs 8,000, Rs 10,000, and Rs 12,000. Soon it approachedand quickly shot bythe standing world record of Rs 13,001 for tea sold at wholesale auction that had been set in 1992 by a tea from another Darjeeling estate, Castleton, which abuts Makaibari. A murmur charged through the audienceand then a hush. Everyone was aware of being part of something special. Seth thought he would see a good price that afternoon for the lot, but he hadnt imagined it would go this high.

Darjeeling tea is often sold not just by single estate like wines, but also by flush, or harvesting season, a term nearly exclusive to tea from the far northeast of India. The fresh shoots from each bush are pickedor, more properly, pluckedevery week or so from mid-March to mid-November, as they gradually progress through a quartet of distinct seasons, beginning with first flush in spring and ending with autumn flush. While Darjeeling teas unique brightness and aromatic flavors set it apart from other similar types of tea, each of the four periods produces a tea with distinctive characteristics.

Makaibaris stock selling that day had been picked during the prime early-summer second flush, when Darjeeling tea is at its most vibrant. Tea from this flush has a sublime body and pronounced muscatel tones, with a mellowed, intense fruitiness and bright coppery color. At its best, Second Flush Darjeeling is unquestionably the most complex black tea the world produces, wrote James Norwood Pratt, one of North Americas foremost tea authorities, with an everlasting aftertaste it shares with no other. Upward the price climbed, past Rs 14,000, Rs 15,000, and Rs 16,000, demolishing the auction world record. Past Rs 17,000.

An agent for Godfrey Phillips India, bidding on behalf of a couple of international clients, agreed to Rs 18,000 per kilo ($390.70). The amount was 120 times more than Darjeeling teas average and almost 250 times the countrys average for tea at auction. A million rupeesten lakhs, as they say in Indiafor the small lot containing fifty-five kilograms (about 120 pounds) of tea. Thats the equivalent of two tea-stuffed suitcases going for more than $10,000 each wholesale.

The European representative desperately wanted the invoice but had reached his authorized limit. He frantically tried to call on his cell phone for the go-ahead to bid higher.

Seth asked for takers for a higher bid.

The European buyer couldnt pick up a signal. No one else said a word. The crowded room smelled of sweat and tension and humidity. Fans whirled overhead.

Seth asked a last time.

In the silent room the agent struggled to get a signal and make his urgent call.

Knocking to Godfrey Phillips at eighteen thousand, Seth finally said, smacking the table with the side of the wooden head of his Raj-era gavel cupped flat in his palm.

Cheers erupted in the auction room and a ringing round of applause. Seth thanked the buyers and participantsand their appreciation of the teas quality. Two of the five chests were destined for Upton Tea Imports in Holliston, Massachusetts, one for Japan, and two to an associate of Makaibaris. The garden had just set a new record for tea sold at wholesale auction.

It was a landmark event, Seth said by telephone from Kolkata. The record still stands. We are unlikely to see it broken for many, many years.

Today tea is grown in forty-five countries around the world and is the second most commonly drunk beverage after water. Its a $90 billion global market. Until just a few years ago, India was the worlds largest producer of tea. Although overtaken by China, it still produces about a billion kilogramsmore than two billion poundsa year.

Tea can generally be classified in six distinct types: black, oolong, green, yellow, white, and pu-erh. All come from the same plant. The difference lies in processing. Nearly all of Indias is black tea, which means that the leaves have been withered and fermented and certain characteristic flavors allowed to develop. (Green tea is neither withered nor fermented, and oolong is only semifermented.) Yet the wide geographic and climatic range of Indias tea-growing areas, from lowland jungle to Himalayan foothills, means that it produces a variety of distinctive black teas.

Next page