Table of Contents

For Scott

The greatest service which can be rendered to any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.

Thomas Jefferson

[Tea] is an exceedingly useful plant; cultivate it, and the benefit will be widely spread; drink it, and the animal spirits will be lively and clear.

Robert Fortune, quoting a Chinese proverb

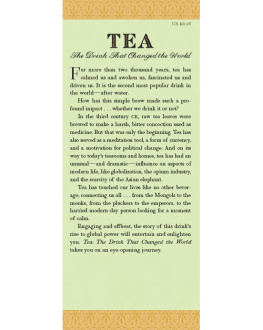

Prologue

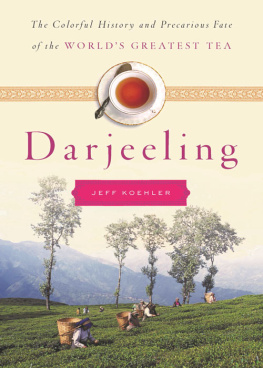

There was a time when maps of the world were redrawn in the name of plants, when two empires, Britain and China, went to war over two flowers: the poppy and the camellia.

The poppy, Papaver somniferum, was processed into opium, a narcotic used widely throughout the Orient in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The drug was grown and manufactured in India, a subcontinent of princely states united under the banner of Great Britain in 1757. Opium was marketed, solely and exclusively, under the aegis of Englands empire in India by the Honourable East India Company.

The camellia, Camellia sinensis, is also known as tea. The empire of China had a near complete monopoly on tea, as it was the only country to grow, pick, process, cook, and in all other ways manufacture, wholesale, and export the liquid jade.

For nearly two hundred years the East India Company sold opium to China and bought tea with the proceeds. China, in turn, bought opium from British traders out of India and paid for the drug with the silver profits from tea.

The opium-for-tea exchange was not merely profitable to England but had become an indispensable element of the economy. Nearly 1 in every 10 sterling collected by the government came from taxes on the import and sale of teaabout a pound per person per year. Tea taxes funded railways, roads, and civil service salaries, among the many other necessities of an emergent industrial nation. Opium was equally significant to the British economy, for it financed the management of Indiathe shining jewel in Queen Victorias imperial crown. While it had always been hoped that India would become economically self-sustaining, by the mid-nineteenth century England was waging a series of expansionist wars on Indias North-West Frontier that were swiftly draining whatever profits could be derived from the rich and vast subcontinent.

The triangular trade in botanical products was the engine that powered a world economy, and the wheels of empire turned on the growth, processing, and sale of plant life: poppies from India and camellias from China, with a cut from each for Great Britain.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the British-Chinese relationship was a tragically unhappy. The Exalted and Celestial Emperor in Peking had officially banned the sale of opium in China in 1729, but it continued to be smuggled in for generations afterward. (Notably, the sale of opium was also forbidden by Queen Victoria within the British Isles. She, however, was largely obeyed.) Opium sales increased quickly and steadily; there was a fivefold growth in volume in the years 1822-37 alone. Finally, in 1839, the leading Chinese court official in the trading port of Canton, rankled by the profligacy of the foreigners and the pestilence of opium addiction among his own people, held the entire foreign encampment hostage, ransoming the three hundred Britons for their opium, then worth $6 million (about $145 million in todays dollars). When the opium was surrendered and the hostages released, the mandarin ordered five hundred Chinese coolies to foul nearly three million pounds of the drug with salt and lime and then wash the mixture out into the Pearl River. In response, young Victoria sent Britains navy to war to keep the lucrative opium-for-tea arrangement alive.

In battle, Britain trounced China, whose rough wooden sailing junks were no match for Her Majestys steam-powered modern navy. As part of the peace treaty, England won concessions from the Chinese that after a century of diplomatic entreaty no one had thought possible: the island of Hong Kong plus the cession of five new treaty or trading ports on the mainland.

Few Westerners had penetrated the Chinese interior since the days of Marco Polo. For two hundred years prior to the First Opium War, British ships had been restricted to docking at the entrept of Canton, a southern trading city at the mouth of the Pearl River. Britons could not officially step foot outside their warehouses, and many had never even seen the city walls, 20 feet thick and 25 feet high and only 200 yards away from the foreigners district. Now, with their triumph in the war, the interior of China was opened to the Britishjust a crackfor business.

With five new cities in which to trade, British merchants began dreaming of the lush silks, delicate porcelains, and perfumed teas stockpiled in the Chinese interior, just waiting to be sold to the wider world. Merchants conceived of the possibility of dealing directly with Chinese manufacturers, rather than the cantankerous middlemen or Hongs who commanded the Canton warehouses. Bankers had visions of untold riches, of mineral wealth, and of crops, plants, and flowersa giant country filled with unmonetized commodities.

The new order established by the First Opium War was an unstable one, however. Forced by British gunboats to sign the intolerable treaties, China, the once proud and self-contained nation, had been thoroughly shamed. British politicians and traders worried that the humiliated Chinese emperor might upset the delicate balance established by the peace accords by legalizing opium production in China itself, thus breaking Indias (and, in turn, Britains) monopoly on the poppy.

An idea now took hold in the City of London: Tea could and must be secured for England. The Napoleonic Wars had long since ended by the time of the Opium Wars, but the brave men who had fought at Trafalgar and Waterloo still held enormous sway over foreign policy and opinion. Henry Hardinge, a great general who had helped defeat Napoleon beside Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington, warned of the risk posed by a defiant China when he was governor-general of India:

It is in my opinion by no means improbable that in a few years the Government of Pekin, by legalising the cultivation of Opium in China, where the soil has been already proved equally well adapted with India to the growth of the plant, may deprive this Government of one of its present chief sources of revenue. Under this view I deem it most desirable to afford every encouragement to the cultivation of Tea in India; in my opinion the latter is likely in course of time to prove an equally prolific and more safe source of revenue to the state than that now derived from the monopoly on Opium.

If China legalized the opium poppy, it would leave a crucial gap in the economic triangle: England would no longer have the money to pay for her tea, her wars in India, or her public works projects at home. Chinese-grown opium would put an end to the shameful economic codependence between the two empires, the unhappy marriage sealed by the exchange of two flowers. It was a divorce that Britain could ill afford.

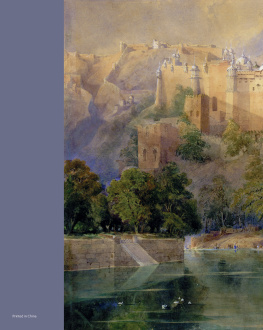

The Indian Himalaya mountain range resembled Chinas best tea-growing regions. The Himalayas were high in altitude, richly soiled, and clouded in mists that would both water tea plants and shade them from the scorching sun. Frequent frosts would help sweeten and flavor their liquor, making it more complicated, intense, delicious.