Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism

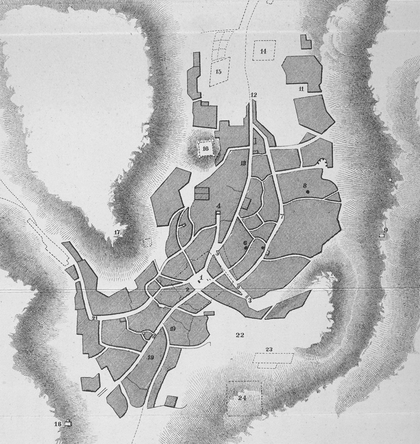

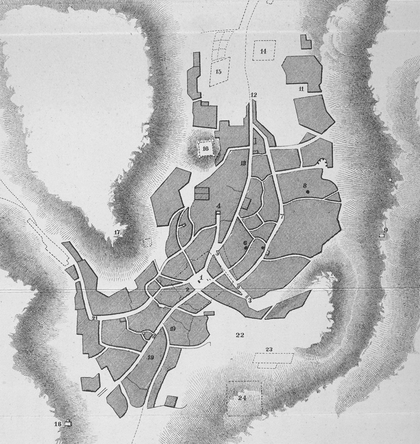

Map of Mecca based on the Chronicles of Mecca.

Places of interest include the Kaaba (No. 1), Muhammads marital home (No. 6), and his birthplace (No. 8).

Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism

Benedikt Koehler

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Front cover, Audience of Venetian Ambassadors in Damascus, painting by Circle of Giovanni Mansueti (14601526), Paris, Louvre Museum.

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom

Copyright 2014 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Koehler, Benedikt.

Early Islam and the birth of capitalism / Benedikt Koehler.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7391-8882-8 (cloth : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-0-7391-8883-5 (electronic)

1. Islam--Economic aspects. 2. Capitalism--Religious aspects--Islam. 3. Economics--Religious aspects--Islam. I. Title.

BP173.75.K645 2014

330.12'2091767--dc23

2014016716

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Chapter 1

The Richest Man in Arabia

First Arabs made a name for themselves in business; their reputation for religious zeal came later. The Bible has Arabs trading in luxury goods; the Roman Pliny thought Arabs are the richest nations in the world, seeing that such vast wealth flows in upon them from both the Roman and the Parthian Empires. The origins of Arab culture in commerce then came into focus.

Muhammad ibn Abdullah, Islams founder, was proud of his descent from Arabias most respected tribe, the Quraysh, who owed their standing to success in business rather than in battle. Muhammad even at the peak of his career was pleased when he heard praise for his own financial accomplishments; he smiled when his deputy Abu Sufyan ibn Harb complimented him, you have become the most wealthy of the Quraysh! Abu Sufyans fawning accolade was not empty flattery, far from it, because Muhammad by then earned annual rents exceeding ten thousand ounces of gold (in todays terms, commensurate with several million dollars). Muhammad was the richest Arab of his time.

Long before Muhammad was born in Mecca (in 570), Arabs had been trading between Europe, India, and China, manning trade expeditions that were big (up to 2,500 camels) and went far (caravans mostly went to Gaza, ships sailed as far as Korea). Such ventures involved considerable logistical challenges: readying goods, selecting staff, equipping camels and ships. But they also required complex financial arrangements: trade expeditions had to be funded, and caravan managers and investors wished to know in advance how to share profits. Meccan traders operated firms with terms that let investors spread their risks and gave managers pre-agreed bonus shares. These companies were structured like venture capital companies and Muhammad had intimate knowledge of how they were set up and workedhis wife Khadija bint Khuwaylid was Meccas most prominent venture capitalist. In fact, Khadija first met Muhammad when she invested in a caravan he managed, and Khadija after they married continued managing her investment portfolio while Muhammad set up in the leather trade; the couple owned a home in Meccas most desirable neighborhood. Muhammad for twenty-five years of married life had daily insight into the practical challenges of running a business.

Khadija was the first convert to Islam. The majority of merchants in Mecca, on the other hand, were hostile to the new creed. The city each year hosted pilgrims of some two hundred denominations and if, as Muhammad wished, worship were reserved for Allah they were liable to stay away. Islam constituted a threat to Meccas business model. The business community first tried to bribe Muhammad to moderate his demands (they offered to make him the richest man in town) but when that failed, boycotted him and drove him out of the city. Muhammad emigrated to Medina and Mecca was left in control by his adversary Abu Sufyan ibn Harb.

In Medina Muhammad shaped two institutions that became in every Islamic city the hubs of civic life: the mosque and the market. Muhammad put several decades of commercial experience into effect by issuing a range of fiscal and commercial provisions; he declared trade on the Medina market exempt from tax and introduced taxes to fund social security payments. He also set a host of commercial incentives: he improved consumer protection; gave guidelines on how commercial contracts were to be drafted; and banned insider trading. The list could go on. But Muhammads flair for commerce in early Islam was not unique; his first three successors all were former professional merchants who adapted commercial conventions as the realm of Islam scaled up from a small-scale civic community to an empire.

The Islamic Empire was successively ruled from three capitals: Medina, Damascus, and Baghdadand evolved into a trade zone bounded by China and the Atlantic where senior officials were appointed without regard to their religious affiliation. In Medina, formerly Byzantine officials introduced a government budget that entitled each Muslim to a fixed annual stipend: this was the worlds first government pension plan. In Damascus, Christian tax officials were instrumental in launching the Islamic gold dinar: a single currency for a single market. In Baghdad, by the early tenth century a fully fledged banking sector had come into being: exchanging gold and silver coins and lending money to government and to merchants who were able to pay money into accounts in one city and draw money in another. These drafts had several namesone of them was the Persian word ak that has come down to us as check.

The money being made in Baghdad was staggering; the caliph Muqtadirs favorite bauble was a silver bird made of 50,000 ounces of silver. But wealth percolating into Baghdad society bred a taste for spending money intelligently. The caliph al Mamun founded a House of Wisdom that gathered and translated works written by Greek philosophers (but for this initiative these works would have been lost to posterity). Muslims also looked East; they explored the religions of India and advanced the study of medicine, mathematics, and geography. To a society that grew rich from trading with distant lands, geography was plainly useful, as was mathematics because counting was very important to run a business. The worlds first accounts that show how to work out compound interest appear in tenth-century Baghdad.

Beginnings

Islamic elites very early achieved enormous wealth and knew what to do with it. Washington Irving, the nineteenth-century novelist whose biography of Muhammad even today does not read dated, noted

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.