Introduction

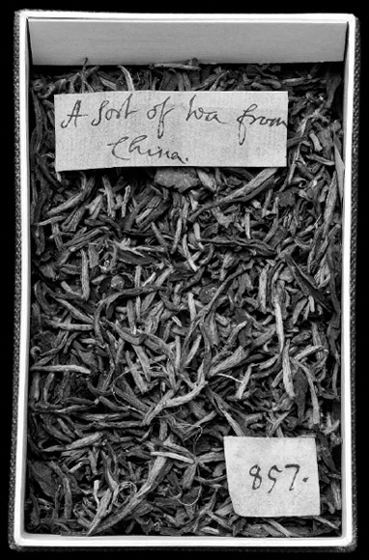

W e encounter Vegetable Substance 857 on a visit to the Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum in London. It occupies a boxboard container about six inches long, lined with white card, covered in black fabric. Through the glass lid, we can just make out an ounce or two of dried leaves: on opening the box their curled forms and brittle textures, mottled with hues of green and brown, emit the faint ghost of an odour. Half-buried in this tiny heap are two scraps of paper inscribed in dark-brown ink by an eighteenth-century hand. One explains that this vegetable substance is A sort of tea from China, the other provides its classifying number, 857. What we are viewing is instantly familiar yet it is a source of wonder. Here, within the temperature-controlled airlock of the Special Collections Room, is a sample of tea prepared for market in China around 1698. Intended for immediate consumption, it nonetheless survives into the twenty-first century, a passage of over 300 years. As such, Vegetable Substance 857 is a unique physical remnant of a commerce that has shaped the patterns and practices of global modernity.

The collection of Vegetable Substances to which this tea belongs were compiled over many decades by the Irish physician and natural historian Sir Hans Sloane (16601753). From a total of 12,523 boxes, around two-thirds are extant. Beginning with specimens he gathered on Jamaica in the 1680s, Sloane eventually collated plant life from across the known world. His method was to store items of botanical interest such as seeds and fruits, as well as vegetable products in which he perceived potential utility for trade or medicine. The Vegetable Substances, spectacular in their range, were nonetheless just one component of Sloanes trove of antiquities, books and natural rarities all bequeathed to the public as the inaugurating repository of the British Museum (and later the British Library and Natural History Museum). Today, the Vegetable Substances share a section of the Darwin Centres eighth floor with Sloanes vast herbarium, also known as a hortus siccus or dried garden. Its samplesof flowers and leaves were dispatched from Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas before being mounted and pressed in London into leather-bound folios (each of which now claims its own Perspex-enclosed shelf). Within these volumes, curator Charlie Jarvis locates cuttings from the tea shrub Camellia sinensis, taken variously in China and Japan around the turn of the eighteenth century. Reading the Vegetable Substances and Sloane Herbarium together, we begin to understand Sloanes intellectual desire to assemble, systematize and understand the whole of nature. The presence of centuries-old tea gradually becomes less surprising, more enlightening.

For many decades, Sloanes Vegetable Substances were scattered miscellaneously in drawers and cabinets across museum backrooms, but recent work by Jarvis and researcher Victoria Pickering means that the contents can now be readily searched and retrieved. This enables us to situate item 857 in historical context. The smaller, numeric label in our box cross-refers with an original manuscript catalogue, which advises that this sort of tea came from M.r Cunningham. Further investigation among Sloanes correspondence and scientific papers at the British Library confirms that this is James Cuninghame (d. 1709), a Scottish ships surgeon who twice travelled to China. It is not clear whether this tea is the produce of the hill country of Fujian, acquired when Cuninghame joined a private trading voyage to Amoy (Xiamen) in 1698, or the local manufacture of Chusan (Zhoushan), where Cuninghame accompanied an abortive East India Company settlement in 1700 and found wild tea trees growing amid other evergreens. But we do know that Cuninghame, the first Briton to examine Chinese plants in their native habitat, was a keen and attentive natural historian who was fascinated (like Sloane) by their characteristics and uses. Tea, he recognized, remained sufficiently unusual to appeal to his friends at home in London: it was both an object of curiosity for students of medicine and botany, and of immense interest to men of trade and lovers of exotic novelty. In this way, Cuninghame reminds us that Britains incipient relationship with China was not simply about the commercial transmission of commodities, but formed a conduit for intellectual and cultural exchange. Early importers of tea to Britain, among whom Cuninghame sailed, brought with them precious knowledge of the beverages origins and consumption in the orient.

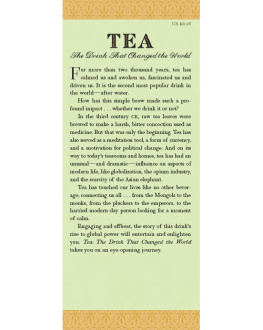

The hot infusion of the oxidized and prepared leaves of Camellia sinensis was an extraordinary innovation when discovered by British drinkers in the seventeenth century. There was no language to describe its flavour, and few directions about how to consume it. Encountering tea for the first time was a creative and experimental process of curiosity and habituation. Grasping for analogies, a physician described tea as being somewhat like Hay mixt with a little Aromatick smell, tis of a green Colour,

Tea became a defining symbol of British identity in a period when it all came from China and Japan: it was not until 1839 that the first Empire tea from Assam found its way to the London markets. So although the history of Britains obsession with tea is often associated in the popular imagination with the nineteenth-century plantations of colonial India and the dramatic races between tea clippers, these aspects of its story were the effect rather than the cause of the widespread demand for tea. Moreover it was Britains appetite for this Asian leaf that led to its international adoption among its former colonies, becoming by one measure the worlds most popular beverage after water. One crucial inference of the Empire of Tea that this book narrates is therefore the trajectory of the British Empire. Indeed, tea was peculiarly central within the complex international currents of cash, commodities, people and ideas that drove British imperialism in the eighteenth century: as the bedrock of a highly lucrative trade with China, as a symbol of the mother countrys arbitrary disposition in North America, as the mainstay of agricultural colonization across South Asia, and as a partner of Caribbean sugar (the other non-native foodstuff with which it transformed patterns of British consumption) in so many humble cups. Through tea, Britain announced and experienced the strangeness of global connectedness, and the gratification of an emerging imperial confidence that flowed reciprocally between the state and the wider populace.