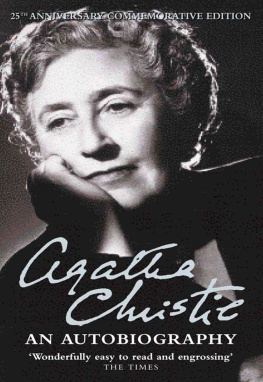

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY

AND OTHER WRITINGS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Editorial Material and Selection Nicholas Shrimpton 2014

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First published 2014

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931016

ISBN 9780191662782 (ebook)

Printed in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

CROSSING the Atlantic on the SS Bothnia in October 1875, Henry James watched his fellow passenger Anthony Trollope at work:

The season was unpropitious, the vessel overcrowded, the voyage detestable; but Trollope shut himself up in his cabin every morning for a purpose which, on the part of a distinguished writer who was also an invulnerable sailor, could only be communion with the muse. He drove his pen as steadily on the tumbling ocean as in Montague Square[.]

Though James was right about Trollopes disciplined working methods, he did not realize what was being written on this particular occasion. For once, Trollope was not busy with a novel. Instead, he was writing An Autobiography.

The result was the only autobiography by a major Victorian novelist. It was also a book that has sharply divided opinion ever since. For some it is one of the truest, most honest autobiographies ever written: an engrossing account of a young man who unexpectedly rescues himself from drift, doubt, and professional failure in his late twenties, and goes on to achieve a happy marriage and successful career. For others it is a dismayingly philistine picture of the life of a professional writer. Preoccupied with contracts, deadlines, and earnings, unblushingly explicit about the methods used to achieve success, emotionally reticent, and factually unreliable, it can be seen as a mere memoir, or self-help manual, rather than as a genuine exploration of the self.

When the book was published, posthumously, in 1883, it certainly encouraged the view of Trollope as an incessantly productive literary journeyman. As early as 1858, the Saturday Review had attacked his fecundity, or the rapidity with which he wrote and published fiction: Trollopes gift was a mechanical skill and the rapid multiplication of his output led to carelessness.

In the early twentieth century this view that the publication of An Autobiography had been a form of reputational suicide took firm hold. Frederic Harrison loved Trollopes fiction but argued, in an introduction to a collected edition of The Chronicles of Barsetshire, that, in his honest Autobiography he artlessly exposed the meagre equipment of his literary workshop. Michael Sadleir, in his influential study Trollope: A Commentary (1927), linked the decline in Trollopes reputation to the appearance of the book:

A few months after his death his Autobiography appeared, and from beyond the grave he flung in the face of fashionable criticism the aggressive horse-sense of his views on life and book-making. Then it was that affectionate depreciation became malevolent hostility; then did the tempest of reaction against his work and against all the principles and opinions that it represented break angrily and overwhelm him.

It is true that An Autobiography fell, in Sadleirs phrase, with a splash into the elegant waters of aestheticism, or, more literally, appeared at a time when the new assumptions of the Jamesian art novel were beginning to make Trollopes mode of High Victorian realism look old-fashioned. But several of the original reviewers praised the book, and it is not the case that it had a decisive effect on his reputation. Those who had previously disliked his novels (such as the critics in the Saturday Review) continued to do so, while other people went on reading and enjoying them. His novels stayed in print throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the period when Victorian art and literature were routinely dismissed, retaining a popular readership despite the academic disapproval or neglect to which they were subjected. Although An Autobiography may not have helped Trollopes reputation, it cannot be said to have destroyed it.

One reason for this is the fact that the account it gives of the creative process is actually more complex than the references to cobblers wax and early morning cups of coffee might suggest. In Trollope gives a remarkable description of the imaginative process by which the writer of realist fiction comes to know and understand his characters:

the novelist has other aims than the elucidation of his plot. He desires to make his readers so intimately acquainted with his characters that the creations of his brain should be to them speaking, moving, living, human creatures. This he can never do unless he know those fictitious personages himself, and he can never know them well unless he can live with them in the full reality of established intimacy. They must be with him as he lies down to sleep, and as he wakes from his dreams. He must learn to hate them and to love them. He must argue with them, quarrel with them, forgive them, and even submit to them.

Thus far, this is an impersonal, third-person account of the matter. But in the next paragraph Trollope acknowledges that he is talking here about his own creative method:

It is so that I have lived with my characters, and thence has come whatever success I have obtained. There is a gallery of them, and of all in that gallery I may say that I know the tone of the voice, and the colour of the hair, every flame of the eye, and the very clothes they wear. Of each man I could assert whether he would have said these or the other words; of every woman, whether she would then have smiled or so have frowned.

This process of living-with could sometimes take on an almost frightening intensity, as Trollope reveals in :

When my work has been quicker done the rapidity has been achieved by hot pressure, not in the conception, but in the telling of the story in circumstances which have enabled me to give up all my thoughts for the time to the book I have been writing. This has generally been done at some quiet spot among the mountains At such times I have been able to imbue myself thoroughly with the characters I have had in hand. I have wandered alone among the rocks and woods, crying at their grief, laughing at their absurdities, and thoroughly enjoying their joy. I have been impregnated with my own creations till it has been my only excitement to sit with the pen in my hand, and drive my team before me at as quick a pace as I could make them travel.

Next page