Eagle Day

Dedication

To the unknown pilot

Chapter One

My God, Life Wouldnt Seem Right

August 67

At sunrise the house named Karinhall was silent. It sprawled, as still as a slumbering animal, a vast unwieldy pile of hewn stone, forty miles north-east of Berlin, amid the sandy plain called the Schorfheide. Yet the silence was deceptive: on this hazy August morning of 1940, eyes were watching everywhere at Karinhall. Through the dark forests beyond the terrace wound fences inset with photo-electric cells, set to sound instant alarm in guardrooms along the boundary. In these razor-edged days, the houses 120-strong security force, under General Karl Bodenschatz, could take no chances.

But this morning, there were few overt signs of trouble; the overlord of this feudal complex, forty-seven-year-old Reichsmarschall Hermann Goring, Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe, was in benevolent mood. As Goring towelled after an icy shower, before donning an ornate silk robe, his valet, Robert Kropp, knew just the gramophone music to choose for his masters serenade this morning lively excerpts from Aubers Fra Diavolo or even Arabella. For today, Tuesday, August 6,1940, all the omens were good.

It was just nine weeks since Dunkirk, six since the Fall of France yet still there was no indication that Great Britain would realise the true hopelessness of her position and sue for peace. Three weeks back, even before Winston Churchills outright rejections of a peace offer, made through the King of Sweden, Hitler, angered by the stalemate, had issued his famous Directive No. 16: since England seemed unwilling to compromise, he would prepare for, if need be carry out, a full-scale thirteen-division invasion of the island on a 225-mile front from Ramsgate on the Kentish coast to west of the Isle of Wight. The code-name for what Hitler styled this exceptionally daring undertaking was Sea-Lion.

But, the directive stressed, prior to any such landing, The British Air Force must be eliminated to such an extent that it will be incapable of putting up any substantial opposition to the invading troops.

To Goring, sipping breakfast coffee, this seemed no insuperable task. The French collapse had given his Luftwaffe fully fifty bases in northern France and Holland; even the short-range planes that accounted for half of the 2,550 machines immediately available Messerschmitt 109 fighters, Junkers 87 (Stuka) dive-bombers were now within twenty-five minutes striking distance of the English Channel coast. Since Julys end, no British convoy had dared to run this formidable gauntlet and as Goring had warned the world through a July 28 interview with a U.S. journalist, Karl von Weygand, to date the Luftwaffes strikes had been childs play, armed reconnaissance only.

And to the top commanders whom hed this day summoned to mull over final details, men such as Generalfeldmarschall Erhard Milch, the Luftwaffes Inspector-General, and Generaloberst Hans-Jurgen Stumpff, commanding Air Fleet Five in Norway, it seemed that Goring hadnt a care in the world. Both Air Fleet Twos Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, and Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle, chief of Air Fleet Three, whose 300-pound bulk earned him the nickname The Monocled Elephant, found him benign, even cocky. To Goring, following the whirlwind Polish and French campaigns, to step up aircraft production beyond the 1939 level of 460 planes a month now seemed pointless and bombers, the proven spearhead of these campaigns, still had priority above fighters.

So this morning, as some present later recalled, it was as much a social occasion as a rehearsal for battle. Resplendent in his sky-blue uniform, Goring seemed more eager to show off the Renoirs in his art-gallery than to discuss tactics and as aides in smartly cut uniforms hovered with brandy and cigars, Kesselring and Sperrle exchanged meaningful glances. Now, with each week that passed, Goring, like any new-rich millionaire, grew more steadfast in fantasy and today his whole strange world, lying at the end of a two-mile avenue flanked by marble lions, would surely be displayed to them anew the silk and silver hangings and the crystal chandeliers the gold-plated baths the private cinema and the bowling alley the model beer-cellar even canary cages shaped like dive-bombers.

Later, if time allowed, the party might pay a visit to what was virtually a private shrine: the tomb of Gorings beloved first wife Karin, on whom in life hed lavished a hundred red roses at a time. Six years earlier, with the full approval of Emmy, his second wife, Goring had not only built this mighty hunting-lodge, naming it after Karin, but had re-interred her here in a sunken vault deep beneath the Schorfheides sandy soil.

Pacing the tapestry-hung corridors in Gorings wake, neither Kesselring, Sperrle, nor the other members of the party were much taken aback by these diversions; by now the Reichsmarschalls way of running an air war was too well known. Though a stream of memoranda countersigned by Goring flooded almost daily from Karinhall, the brunt of planning aerial missions in detail rested as squarely as always on the Air Fleet chiefs and their staffs. As a thrusting Minister of Aviation whose drive, from 1934 on, had wrought the Luftwaffe into the worlds most powerful air-arm, Gorings disdain of technical detail had still been such that he met his inspector-general, Erhard Milch, just once every three months.

It wasnt that his Air Fleet commanders didnt raise objections over the forthcoming battle but Goring, in euphoric mood, brushed them cheerfully aside. To Sperrle, the target selection seemed faulty; if Britain was 100 per cent dependent on seaborne traffic, shouldnt ports be the main target? But Kesselring just couldnt see it. One swamping attack on a key target say London was almost always the answer.

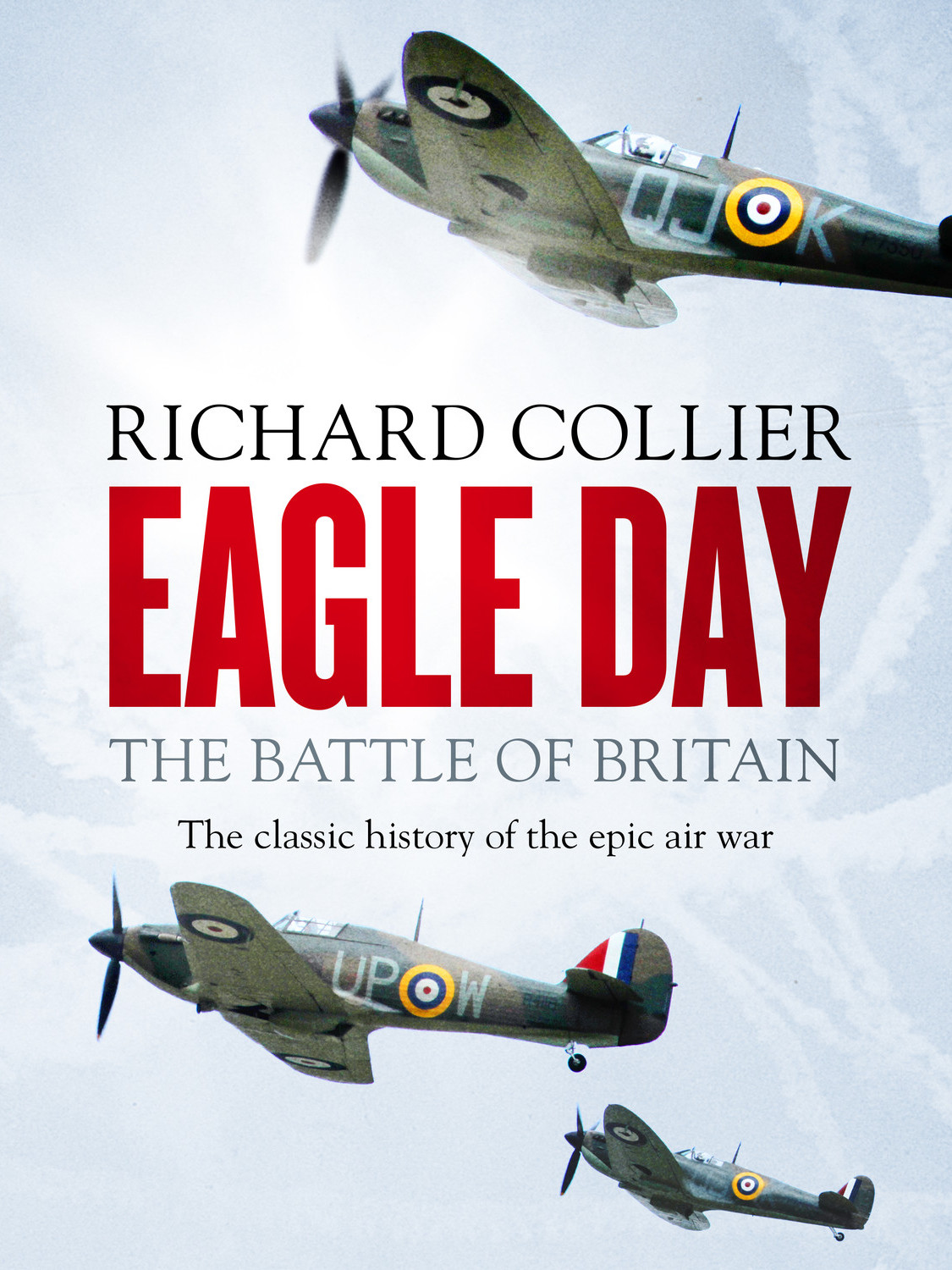

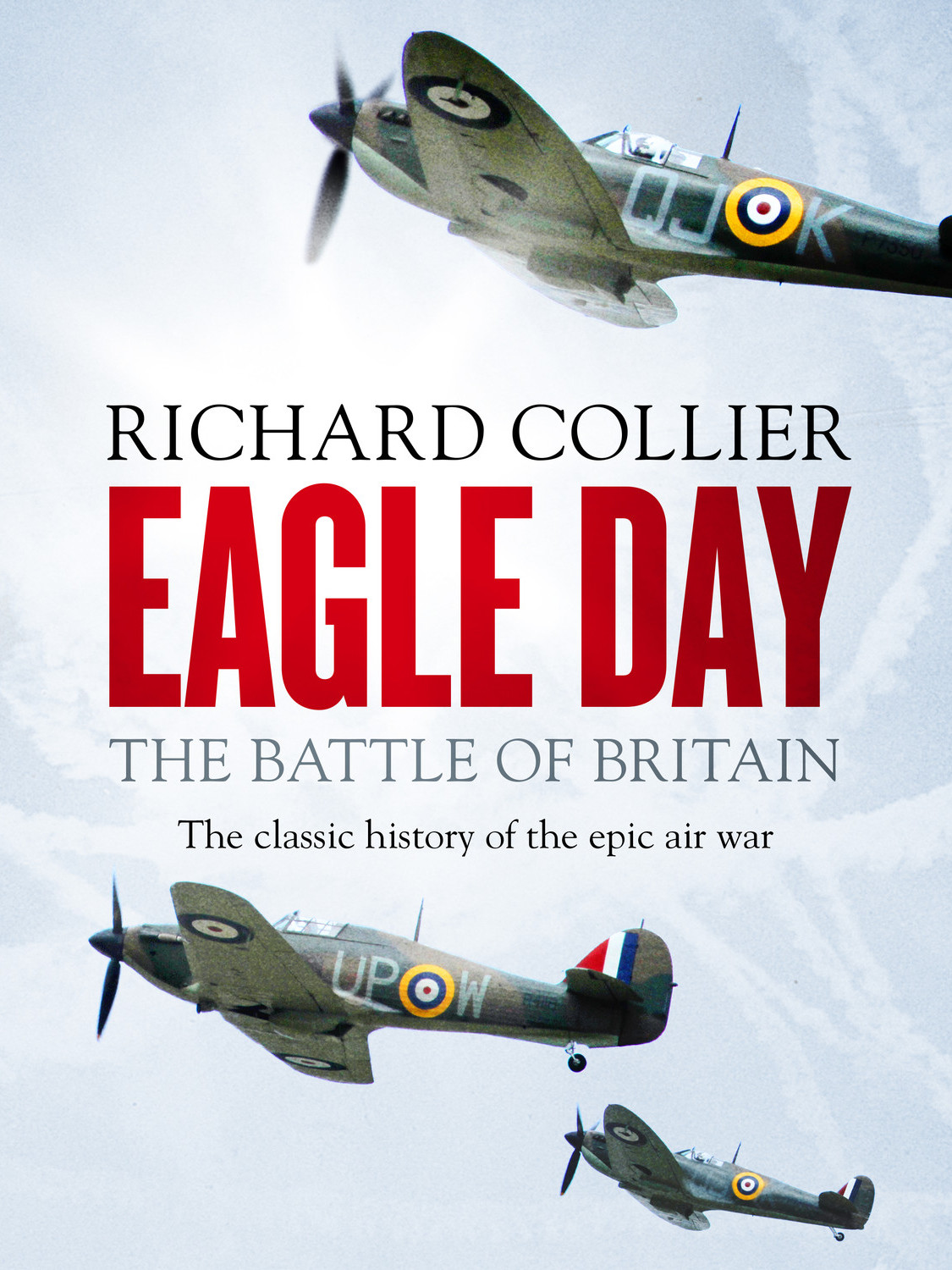

As things stood now, the main attack plan Adlerangriff, or attack of the Eagles, to come into force on receipt of the codeword Adler Tag (Eagle Day) was scattered along the whole invasion front: airfields, ports, even aircraft factories. Following hard on this, more mass-attacks code-named Lichtmeer (Sea of Light) were slated to wipe out all the R.A.Fs night operational bases between the Thames and the Wash.

Poring over a map, the three men did check over key targets the radio direction finding (later called radar) stations on Englands south coast, for a start, though their true function was still something of a mystery the coastal airfields, naturally, Manston, Hawkinge and Warmwell in Dorset the major airfields such as Biggin Hill, lying inland, eighteen miles south of London.

As yet no final date could be fixed from August 5 onwards, meteorologists predicted a high-pressure zone moving slowly towards the Channel from north-west England but on one score Goring was adamant. By the yardstick of the Polish and French campaigns, the Royal Air Force should be out of the picture in four days flat.

Hie decision made, Goring led his guests towards the showpiece hed all along had in store for them: the vast model railway that snaked beneath Karinhalls rafters, past miniature farms and forests, under papier-mache mountains six feet high. A shade bemused, the field-marshals watched as their host pressed a button and a glinting squadron of toy bombers glided on taut wires from the eaves to shower their bombs on a model of the French Blue Train. Toy signal lights changed from red to green, from green to red, and Goring relaxed, content.