Sean Egan has contributed to, among others, Billboard, Book Collector, Classic Rock, Readers Digest, Record Collector, Tennis World, Total Film, Uncut, and RollingStone.com. He has written or edited several books, including works on the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Clash, Manchester United, Coronation Street, Tarzan, William Goldman, and James Bond. His critically acclaimed novel Sick of Being Me was published in 2003, while his 2008 collection of short stories Dont Mess with the Best carried cover endorsements from Booker Prize winners Stanley Middleton and David Storey. His 2002 book Jimi Hendrix and the Making of Are You Experienced was nominated for an Award for Excellence in Historical Recorded Sound Research.

I wish to express my grateful thanks to Corinna Bechko, Tom Burman, Christopher Gordon, Rich Handley, Linda Harrison, Doug Moench, Don Murray, Christopher Sausville, Austin Stoker, and Rupert Wyatt for granting interviews for this book. In addition to these interviews, I drew upon interviews I had conducted previously with Ron Harper, Rob Kirby, James Naughton, and Roy Thomas, some of which material is hitherto unpublished. I am also privileged to be publishing for the first time selections from interviews conducted by Dean Preston with makeup staff who worked on Tim Burtons 2001 Planet of the Apes. I wish to extend my grateful thanks to Dean for granting the relevant permission to use quotes from the following individuals: Mark Alfrey, Cristina Ceret, Jamie Kelman, Kazuhiro Tsuji, and Eddie Yang. I would additionally like to thank Mark Arnold, Hunter Goatley, Edward Gross, and Dean Preston for answering queries and providing introductions.

Becker, Lucille Frackman. Pierre Boulle. Woodbridge, CT: Twayne, 1996.

Berenato, Joseph F., and Rich Handley, eds. Bright Eyes, Ape City: Examining the Planet of the Apes Mythos. Edwardsville, IL: Sequart, 2017.

Bond, Jeff, and Joe Fordham. Planet of the Apes: The Evolution of the Legend. London: Titan, 2014.

Cinefantastique (Summer 1972). Multiple articles.

Conlin, William, dir. Making Apes: The Artists Who Changed Film. Cleveland, OH: Gravitas Ventures, 2019. DVD.

Dunne, John Gregory. The Studio. New York: Vintage, 1998.

Egan, Sean. Tarzan: The Biography. London: Askill, 2017.

Five Questions with Ape-a-Holics Anonymous. Toys from the Attic, catalog 3, September 1995.

Handley, Rich, comp. The Complete Planet of the Apes Comics Index. Last updated January 22, 2021. http://hassleinbooks.com/pdfs/POTAComics.pdf.

Heston, Charlton. The Actors Life: Journals 19561976. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1978.

Pendreigh, Brian. The Legend of the Planet of the Apes, or How HollywoodTurned Darwin Upside Down. New York: Macmillan, 2001.

Planet of the Apes (Curtis Magazines/Marvel Comics; August 1974February 1977). Multiple articles.

Russo, Joe, Larry Landsman, and Edward Gross. Planet of the Apes Revisited: The Behind-the-Scenes Story of the Classic Science Fiction Saga. New York: Griffin, 2001.

Salisbury, Mark, ed. Burton on Burton. Rev. ed. London: Faber and Faber, 2006.

Sausville, Christopher. Planet of the Apes Collectibles: An Unauthorized Guide with Trivia & Values. Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 1997.

Woods, Paul A. The Planet of the Apes Chronicles. London: Plexus, 2001.

WEBSITES

Hunters Planet of the Apes. https://pota.goatley.com/.

Planet of the Apes: The Sacred Scrolls. https://planetoftheapes.fandom.com.

Planet of the Apes: The Television Series. http://potatv.kassidyrae.com/articles.html.

Roddy McDowall Readers Nook. http://www.xmoppet.org/nfReader.html.

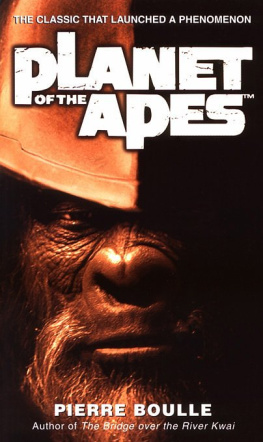

Frenchman Pierre Boulle was the most improbable progenitor of a mass-media science fiction franchise. For a start, Boulle even disputed the SF categorization of his novel La plante des singes, published in France in 1963 by ditions Julliard. It is a story, and science fiction is only the pretext, he told Jean Claude Morlot of Cinefantastique magazine. A World War II hero and intellectual, Boulle would have probably even detested the word franchise. He was delighted with the 1968 motion picture adaptation of his novel, but the resultant relentless commercial exploitation of his original idea by media and merchandise manufacturers was a world removed from his stern-browed hinterland.

Boulle was born in Avignon, France, in 1912. He graduated from college in 1932 with a degree in engineering, but, as with so many people in that era, his professional plans were disrupted by Herr Hitler. His army stint was followed by a post-invasion sign-up to the Free French, for whom he worked as a spy, helping to repel Japanese invasion forces in China, Burma, and Indochina.

Boulle began writing at the dawn of the 1950s. His first novel was spy tale William Conrad, which gained enough attention to be adapted for an episode of Playhouse 90 on American TV network CBS. He came to true prominence in 1952 with his third book, Le pont de la rivire Kwa, a powerful and harrowing novel set during World War II in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. It was translated into English two years later as The Bridge over the River Kwai. The book sold six million copies in the United States, but English was one of only twenty-two languages in which it was ultimately issued.

In 1957, director David Lean turned the book into a classic piece of cinema under the slightly different title The Bridge on the River Kwai. The film depicts the rollercoaster mental ride of British Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson (Alec Guinness) as he first attempts to sabotage the bridge built by POW Allied manpower on the Burma-Siam railway, then begins to take pride in his work, before finally being jolted back to reality as he realizes he is aiding the enemy. It picked up seven Oscars, including Best Picture.

La plante des singes was Boulles eleventh book. He later explained to Cinefantastique that its origins lay in a visit to a zoo. I watched the gorillas. I was impressed by their human-like expressions. It led me to dwell upon and imagine relationships between humans and apes.

For its English-language publication, La plante des singes was tackled by Pierre Boulles usual translator, Briton Xan Fielding. The latters adaptation is generally smooth, although occasionally stilted (They are now accustomed to this unusual manifestation on my part). In fact, the biggest problem with it stems from nomenclature. In French, the only way of distinguishing between monkey (a small simian with a tail) and ape (a large simian sans tail) is by placing the word grand in front of the word singe. There are no monkeys in the narrative, but Fielding chooses to use monkey throughout, with just ten uses of ape or one of its variants in the entire text. (One of them, in fact, occurs when the protagonist tells a simian that on Earth the verb to ape means to imitate.) The British edition even extended this linguistic and zoological error to the cover: whereas the 1963 American publication of the book from Vanguard Press was wisely titled Planet of the Apes, in 1964 Britains Secker & Warburg gave the book the name Monkey Planet, which, in addition to being wrong, lacks flow.

Boulles novel uses a framing device, the narrative bookended by the third-person portrayal of Jinn and Phyllis, a wealthy couple who are spending a blissful holiday in the vacuum of space, far away from inhabited stars. Pseudo-science gives way to an unexpectedlyand probably consciouslyantediluvian note when the pair discovers floating in the cosmos a classic message in a bottle. Its contents transpire to be a large number of very thin sheets covered in tiny handwriting in the language of Earth, with which Jinn is familiar after having been partly educated on that planet. (This notion of a universal Terran language will be contradicted several times in the text.) When the two begin to read the manuscript, the narrative switches to the first-person account of Ulysse Mrou, the French author of the discovered manuscript.