The Great Apes

The Great Apes

A Short History

Chris Herzfeld

Translated by Kevin Frey

FOREWORD BY JANE GOODALL

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

English translation copyright 2017 by Kevin Frey.

Originally published as Petite histoire des grands singes. Editions du Seuil, 2012.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Bulmer type by Newgen North America, Austin, Texas.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-22137-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017940993

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

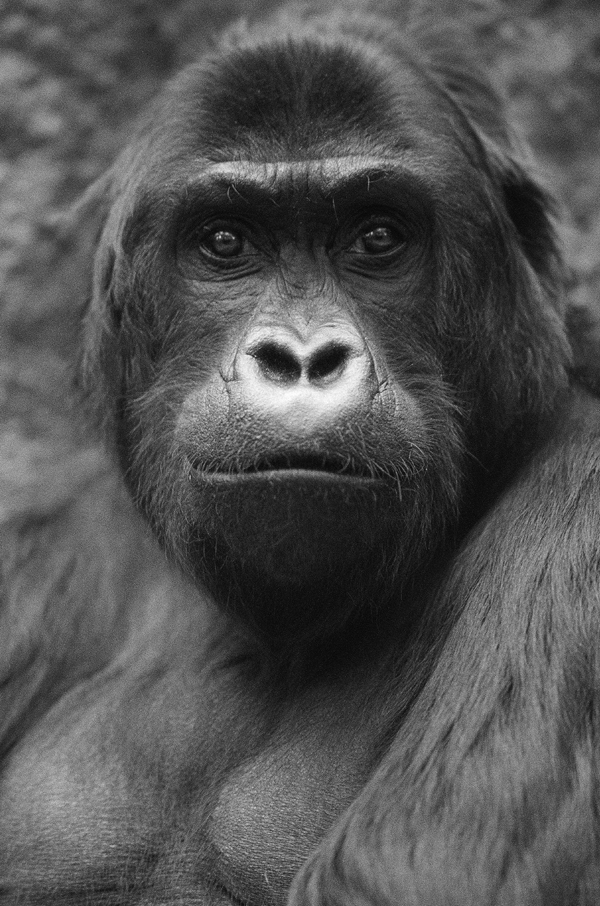

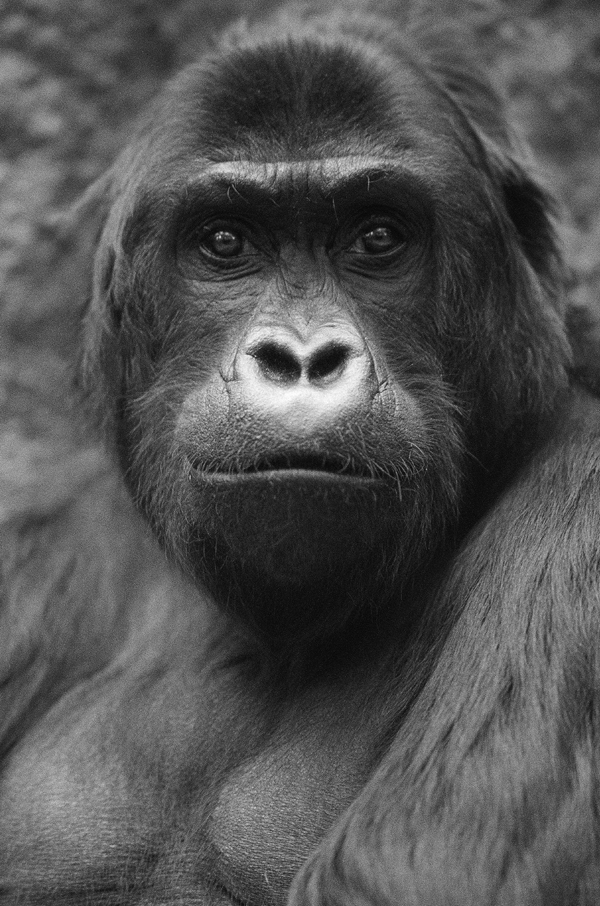

: Victoria (June 9, 1968May 21, 2016), Antwerp Zoo, 1996. (This portrait appears in the book Les grands singes: Lhumanit au fond des yeux, by Pascal Picq, Dominique Lestel, Vinciane Despret, and Chris Herzfeld [Editions Odile Jacob, 2005], Editions Odile Jacob/Chris Herzfeld, MNHN, 2005)

Contents

BY JANE GOODALL

Foreword

WE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN FASCINATED BY the great apesorangutans, gorillas, bonobos, and chimpanzees. Hardly surprising since we are, in fact, the fifth great ape! Today we know quite a lot about these amazing beingsbut when I first went to Tanzania to try to observe chimpanzees in the wild, almost nothing was known about any of the apes in their natural habitat with the exception of the mountain gorilla, which had been studied by George Schaller. And not much was known about ape behavior in captivity, either. I read all that I could find on the subject, and I went to look at the two pathetic individuals in the London Zoo. I learned most from a book called The Mentality of Apes, by Wolfgang Kohler, who worked with a colony of chimpanzees that had been established at Tenerife in the Canary Islands. His observations were extremely revealing.

It was in 1960 that I arrived in the Gombe National Park, site of what is now a field study of chimpanzees spanning nearly sixty years. Back then my biggest problem was that the shy apes ran off as soon as they saw me. But eventually, after several months, they began to lose their fear, and I was able to learn more and more about their fascinating social structure and way of life.

When I went to Gombe I had not been to college. But after I had been in the field for over a year my mentor, Louis Leakey, got me a place at Cambridge University to work for a PhD in ethologyhe said there was no time to get a BA first, but that I would need a PhD if I was ever to get my own funding. Imagine my shock to be told by some of the erudite professors that I had conducted my field research all wrong. I should have given the chimpanzees numbers, not names. And I could not talk about them having personalities, minds capable of rational thinking, and certainly not having emotions because all these characteristics, I was told, were unique to the human. The difference between us and other animals, it was maintained, was one of kind, not degree. Fortunately I had had a wonderful teacher during my childhood who had taught me that the professors were wrongmy dog, Rusty! And eventually science came to realize that we are not so unique after all. We are part of, not separated from, the rest of the animal kingdom.

Today many field studies of chimpanzees have been conducted in different parts of Africa, and also of gorillas, bonobos, and orangutans. All of these animals commonly show behavior that reminds us of some of our own. There is their nonverbal communicationall of them kiss, embrace, hold hands, bow, and beg for food (or reassurance) with their palms up. They show emotions that may be similar toor even the same asthose we call joy and sadness, fear and despair, anger and frustration. Chimpanzees are territorial. The adult males of a community patrol the boundaries of their territory and, if they encounter individuals from a neighboring social group, they may chase and attack, leaving the unfortunate victims to die of wounds inflicted. However, again like us, all the apes show compassion and even true altruismas when an unrelated individual adopts an infant whose mother has died and who has no older brother or sister to care for it.

All the apes can make and use tools. Moreover, different communities of apes use different objects for different purposes, indicating the behavior is learned: infants and juveniles watch closely and imitate the actions of adults. Since one definition of culture in humans is behavior that is passed from one generation to the next through observational learning, we can say that the apes have their own primitive cultures. We continue to learn more and more about the intellectual abilities of the great apesthey can tackle complex tasks on computers and learn several hundred signs of American Sign Language (ASL). They can recognize themselves in mirrors. They can understand the wants and needs of others and respond appropriately. They have a theory of mind. Some captive individuals love to paint, and those knowing ASL may spontaneously inform you of what their paintings represent.

It is because of these humanlike qualities that the great apes, particularly chimpanzees and orangutans, have been sold as pets, taken into homes, dressed up, and treated as children. They are charming and entertaininguntil, around age six or seven, they grow out of infancy and no longer want to behave like human children. At this point, stronger than the humans who own them and potentially dangerous, these unfortunate pets may be confined to a cage, tied up on a chain, sold to a bad zoo or circus or, until very recently, used in medical research.

It is well known today that the training of young apes for entertainment typically involves harsh punishment. They will learn through reward systems, but in show biz the trainer wants instant obedience, and this is most speedily obtained through fear. The lives of ex-performers are similar to those of ex-pets.

In the composition of our DNA, we, chimpanzees, and bonobos differ by only just over 1 percent. In fact, the geneticists tell us that the main difference is in the expression of genes that can be influenced by the environment. There are also remarkable similarities in the composition of our blood, immune system, and anatomy of the brain. Gorillas and orangutans are only slightly less different in their biology.

Because of these striking similarities in biology and physiology, many chimpanzees and some bonobos have been extensively used in psychological and medical research. Physical contact with the mother is very important for infant apes. Some infant chimpanzees were taken from their mothers and kept in isolation to produce models that resembled depression in human infants. Others, confined in metal cages only five by five feet, were infected with diseases such as polio, hepatitis, and HIV-AIDS that other animals, less like us, cannot be infected with. The hope, of course, was to find cures and vaccines that would benefit humans. These experiments typically inflicted a great deal of suffering, both physically and psychologically. Nor did they result in medical breakthroughs. In some cases treatments that benefited the apes proved harmful to human patients. And in other cases human trials for certain treatments that did eventually prove to be beneficial for humans were delayed because the medications were harmful to the ape subjects. Moreover, a number of chimpanzees took part in some of the first flights into space. The rigorous training undergone by these youngsters was brutally rigorousone of the first human astronauts told me that he could not have endured training of that sort.

Next page