Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

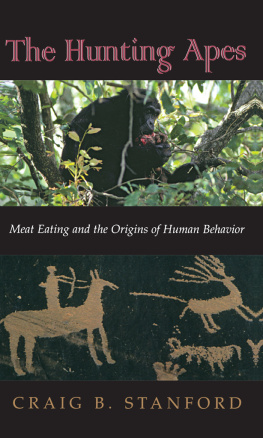

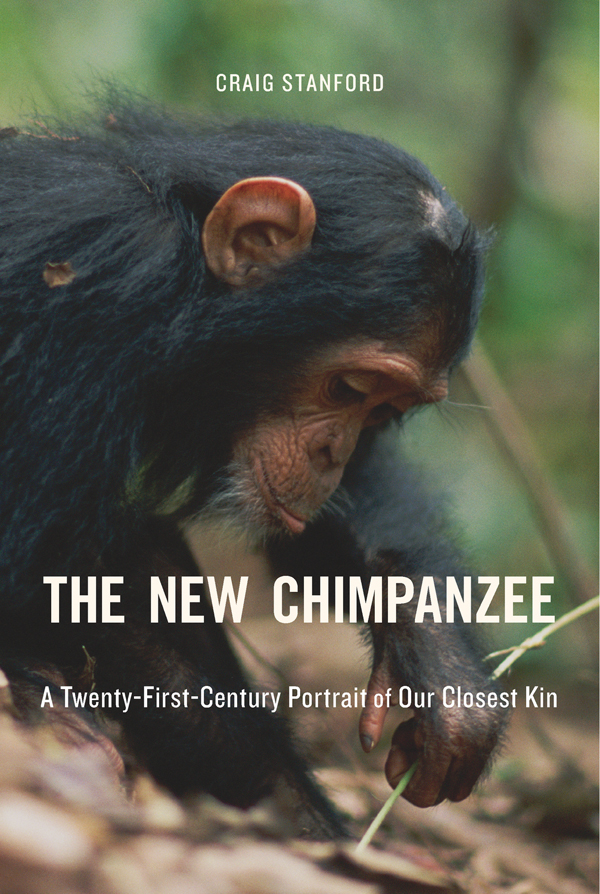

CRAIG STANFORD

The New Chimpanzee

A Twenty-First-Century Portrait of Our Closest Kin

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England 2018

Copyright 2018 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket design: Marcus Ferolito

Jacket photo: Minden Pictures

978-0-674-97711-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

978-0-674-91975-4 (EPUB)

978-0-674-91976-1 (MOBI)

978-0-674-91977-8 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Stanford, Craig B. (Craig Britton), 1956 author.

Title: The new chimpanzee : a twenty-first-century portrait of our closest kin / Craig Stanford.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017040032

Subjects: LCSH: ChimpanzeesBehavior. | Primatology.

Classification: LCC QL737.P94 S727 2018 | DDC 599.885dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017040032

Dedicated to the generations of chimpanzee researchers from Jane Goodall to the present day

Contents

Over the past two decades, scientists have made dramatic discoveries about chimpanzees that will change the way we understand both human nature and the apes themselves. Although there is a rich history of chimpanzee field research going back nearly sixty years, almost all the findings discussed in this book have been made just since the turn of the millennium. From genomics to cultural traditions, well consider our close kin in a new light and ask what this information may mean for a new and improved understanding of human nature.

Studying wild chimpanzees is the profession of a very small number of people in the world. At any one time there are probably fewer than a hundred scientists and their students actively engaged in chimpanzee field observation and study. The number of full-time professors in American universities whose careers are focused mainly on wild chimpanzee research is perhaps a dozen. Add in the scholars and conservationists doing work in related areas, and the global army of chimpanzee watchers is a few hundred strong. The available funding for the work they do is a fraction of that given to scientists in other endeavors. Yet the results of new studies are front-page news and are rightly touted in the international media for the clues they provide about human nature.

My own involvement with chimpanzees came about fortuitously. In the late 1980s I was conducting my doctoral research in Bangladesh on a previously little-known monkey called the capped langur. I was living in a ramshackle cabin on stilts at the edge of a rice paddy, spending my days following a group of the monkeys on their daily rounds in the nearby forest. Capped langurs are handsome animals, their gray backs set off by a flame-orange coat underneath and a black mask of skin for a face. Unfortunately, their behavior is not as interesting; they traveled only a hundred meters per day and spent nearly all their waking hours calmly munching on foliage. The most interesting observation I made in thousands of hours with the langurs was the fatal attack on an old female by a pack of jackals. Jackals were not thought to prey on animals as large as eight-kilogram monkeys, but with the extirpation of leopards and tigers in the area, they may have taken on that role. As I strolled along behind the group one afternoon, observing the matriarch feeding on the ground right in front of me, a pair of jackals burst from a thicket, grabbed her, and dragged her off. It was a vivid demonstration for me of the potential for predators to make a powerful impact on the survival of an individual, and on the population of monkeys in this forest.

As I looked ahead to the completion of my PhD and considered postdoctoral options, I sent letters to a number of primate researchers in Africa and Asia proposing projects that involved the study of predations effects on wild primate populations. A colleague suggested I write to Jane Goodall. Goodalls field site in Tanzania had been attacked by a rebel militia in 1975. Four Western students were kidnapped and held for ransom in neighboring Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Although all were eventually released unharmed, the park had been generally off-limits to visiting researchers for more than a decade. I mailed a thin blue aerogramthis was pre-Internetexpecting no reply. When I returned to Berkeley months later, a letter from Goodall was waiting, inviting me to come to Gombe to study the predator-prey interactions between chimpanzees and the red colobus monkeys, whose flesh they so relish. A year later, with a permit from the Tanzanian government and a shoestring budget in hand, I arrived to begin several years of back-and-forth travel to Gombe to study the hunting behavior of chimpanzees and its impact on the behavior and population biology of the monkeys they hunt.

The worlds most famous study of animal behavior is located in a former British colonial hunting reserve, now a tiny but important jewel in Tanzanias national park system. Its an oblong strip of forest and hills, about ten miles long and two miles wide, hugging the shore of Lake Tanganyika, two hours by boat from the harbor town of Kigoma. Before Goodalls arrival, Kigoma was best known for its harbor and its proximity to Ujiji, where the newspaper reporter Henry Morton Stanley found the missionary doctor and explorer David Livingston in 1871. It was a sleepy port town with one main dirt road, a few cafs, and a lot of ramshackle market stalls. These days Kigoma is bustling; its the jumping-off point for ecotourists headed to either Gombe or Mahale National Parks to see wild chimpanzees. Beginning in the 1960s it was the home of Goodall and a team of Tanzanian assistants, soon joined by students from North America and Europe who documented the intimate details of the lives of wild apes. It is sacred ground for any student of animal behavior.

I had come to Gombe mainly to study red colobus monkeysthe favored prey animal when chimpanzees go huntingand their relationship with their predators. Unlike most researchers who arrive at Gombe to study chimpanzees, I was fairly ignorant about their celebrity status. I knew that each member of the same matriline bore a name starting with the same letter, but the names Fifi, Frodo, Gremlin, and Goblin bore no special meaning to me at the start of my study. This would soon change; spending long hours in close quarters with chimpanzees, you cannot help becoming immersed in their lives and personalities. The daily life of a researcher is organized around the daily lives of the animals; you go where they go, when they go, resting when they rest and sweating up steep hills right behind them.

This book is about the lives of chimpanzees living where they belong, in the tropical forests of Africa. Most of us who have spent time with wild chimpanzees have an uneasy relationship with captive research and the ethics of keeping and studying apes in zoos, laboratories, and the like. Psychologists working in laboratories and primate centers have made amazing discoveries about the workings of the chimpanzee mind. These discoveries hold great promise for a deeper understanding of our own intellect and the meaning of intelligence. On the other hand, these researchers work with chimpanzees that are locked up in enclosures that, however artfully designed, cannot mask the fact that the apes are prisoners. In the best-case scenario, large and well-funded primate centers maintain their chimpanzees in large social groups that occupy spacious outdoor enclosures. In such places, detailed observations of social behavior are possible that could never be accomplished in the rugged, dense forests in which chimpanzees naturally live. But spaciousness is relative. A very lucky captive chimpanzee might spend his life on a well-landscaped two-acre island. The same ape, if raised in Africa, would spend a lifetime traversing up to fifty square kilometers of forest. Captivity provides freedom from hunger, predators, and disease, but with the loss of environmental enrichment beyond measure. A cage is a cage, no matter how large or well designed. Moreover, research on behaviors that evolved in an African forest should obviously be done in an African forest. For this reason I have chosen to focus on what we have recently learned about chimpanzees in the wild, and only occasionally introduce captive findings, exciting though they may be in their own right.