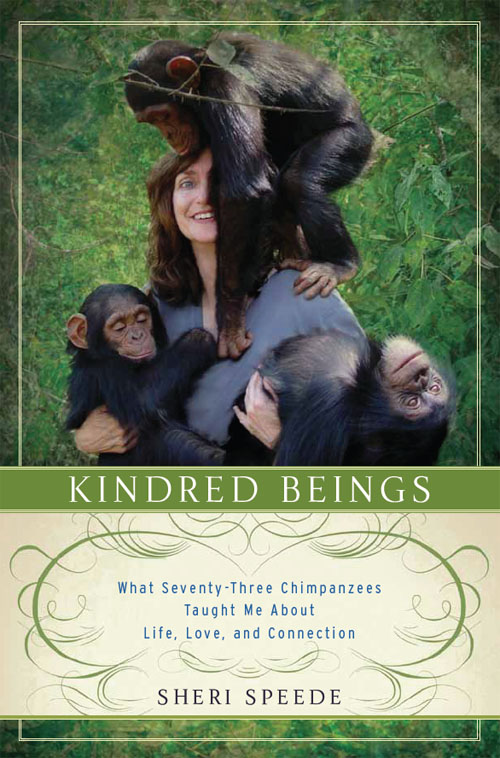

This book is written in loving memory of

Sara Katherine and Lena Pearl.

And it is dedicated to the volunteers: You brought your open hearts and enthusiasm from Australia, Brazil, Cameroon, Canada, England, Finland, France, Holland, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States. You survived pit latrines, cold baths, couscous, cockroaches, long exhausting workdays with far too little rest, and candlelit nights for months on end. Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue Center was built on your backs. Only a few of you are mentioned by name in the following pages, but with deep gratitude and respect, I dedicate this book to all of you.

Contents

O n September 24, 2008, beloved elder chimpanzee Dorothy lay down on the grass at the edge of the forest in a somewhat obscure African sanctuary and died. About five decades earlier, when Dorothy was an infant, poachers supplying the illegal ape meat trade killed her mother and took her captive. She spent most of her sad life chained by her neck as a hotel tourist attraction, but she died among friends who loved her at Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue Center in Cameroons Mbargue Forest.

The morning after Dorothys death we conducted a small funeral service for volunteers, our African staff, and people from the village community who came to pay their respects. Afterward, Dorothys longtime caregiver, Assou Francois, pushed her body in a creaky wheelbarrow toward her gravesite, which had been prepared beside the twenty-acre forested enclosure where she had lived. With a small procession of staff and volunteers, I followed behind. As we neared the enclosure, the twenty-five chimpanzees who had lived with Dorothy heard the wheelbarrow and came out of the forest. As they lined up at the fence line, straining to see her body, I instructed Assou to pull the wheelbarrow close to the fence and stop. As I caressed Dorothys head, and the chimpanzees she loved best gazed at her a final time in silent grief, volunteer Monica Szczupider snapped a photo.

After we buried Dorothy, I saw Monicas picture and hardly gave it a second thought, but this snapshot of emotion soon would be seen around the world. After Monica won a National Geographic photo contest and the magazine published the funeral photo in a glossy double-page spread, numerous other magazines and newspapers also published it. Several journalists interviewed me about it. Invariably, they asked me if I had been surprised by the chimpanzees reactions to Dorothys death.

No, I wasnt surprised in the slightest, I always answered honestly.

After working closely with chimpanzees for years, I took for granted their capacity for a broad range of deep emotions. I had always been deeply sympathetic to the suffering of animals; their particular vulnerability and innocence awakened the compassionate defender in me, enough so that I had dedicated my career to it even before coming to Africa. But my direct experience with captive adult chimpanzees was something different. They were so much more similar to me than either of us was to any other animal. In these chimpanzees I recognized another kind of people, like me in many ways, unlike me in others. They were also animals, they were also apes, and so was I an animal and an ape. In the face of the chimpanzees profoundly familiar ape consciousness and in the genuine friendships that grew between us, I became a more fully realized human animal. I knew chimpanzees to be charismatic and complicated. Not all were always nice. I had seen callous cruelty in their hierarchical societies, and I also had seen kindness and compassion. As the founder and director of this African sanctuary, I was equally committed to every single chimpanzee who lived here, but I cannot say I liked them all equally. Dorothy was kind. I admired her, I loved her, and I knew the chimpanzees loved her too.

Because I knew Dorothy and for years had observed her role in her chimpanzee society, I wasnt surprised by the chimpanzees grief over her death. The human reaction to Monicas photo was a different matter; it did surprise me. Although we share more than 98 percent of our DNA with chimpanzees, and this genetic similarity had become common knowledge, often cited by popular media, I knew that few human people could really comprehend the intelligence and emotional complexity of chimpanzees any more than I had understood it before I worked with them. That this photo showing a simple expression of grief drew such intense interest around the world told me that many of my kind might have opened their hearts to a real understanding that among us animals there is an evolutionary continuum. My initial inspiration to write this book sprang from the worlds reaction to the photo of Dorothys funeral procession. My memory of her life was a compelling inspiration throughout it.

Chimpanzees are still killed for meat, taken captive as pets, and cruelly exploited in biomedical and entertainment industries. The stories of Dorothy and her circle of friends and family need to be told and understood. I tell the stories as honestly as I can, not as an unbiased scientist, but more as a loving ambassador who has attempted to understand them. My personal story, while certainly not as important, is inextricably linked to theirs.

I was born to a blue-collar family in Jackson, Mississippi, the heart of social conservatism, racial segregation as a matter of right and wrong, and the Baptist Bible Belt. My mother was a very smart and loving woman who appreciated beauty in nature as much as anyone Ive ever known. She had a great sense of humor, but also an underlying sadness that affected her, and her family, throughout her life. Perhaps it was her suffering that also gave rise to her sweet sensitivity for the worlds vulnerable and downtrodden, which seemed out of place in the 1960s and 1970s South. My father was a firefighter who anticipated every hunting season with the excitement of a childs countdown to Christmas. Although he brought home the meat of the wild animals he killed many times, I remember him bringing home a whole deer to clean in our backyard only once, when I was quite young. Standing at our back door in my pajamas one winter evening, I watched Daddy, blue eyes twinkling, proud and triumphant, standing over the body of that beautiful buck as he lifted the head by a long antler to facilitate my full appreciation. I took one look at the pretty face and the glazed, lifeless brown eyes and ran to my room sobbing. I would never be a hunter, and as it turned out, my younger brother never took to it very enthusiastically either. I suppose we were a disappointment, but my father tried to make the best of it. He took my mother, my younger brother, and me camping every summer on the Pearl Rivers sandbars, where we swam, water-skied, built bonfires, and fished. For the sake of parental tolerance and my love of fried fish and hush puppies, I managed to mostly sublimate my tender feelings for fish. We went weeks without baths or telephones while my fathers beard seemed to grow longer with every Miller Lite. This was his element, where I thought he was the most competent person in the world. The older I got, the less I liked these escapes from modernity, but they taught me skills and a tolerance for uncomfortable living conditions that would one day be valuable in my travels through rural Africa. Nothing about the outdoors frightened me.

I went to college at Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge, three hours from my Mississippi home. During my freshman year on campus, I met an instructor of a Korean martial art called tae kwon do and soon became his student at the school he operated with a partner. Training at the school of these skilled and dedicated teachers awakened the athlete in me. I took my training seriously, and while I was still in college I earned my first-degree black belt; years later I earned my second-degree. Tae kwon do gave me something more than physical fitness and self-defense skills. It taught me to act in the face of fear, including my fear of failure.

Next page