with photographs and drawings by the author

Frans de Waal

For Jan van Hooff I put for a generall inclination of all mankind, a perpetuall and restlesse desire of Power after power, that ceaseth onely in Death.

THOMAS HOBBES, 1651

xi

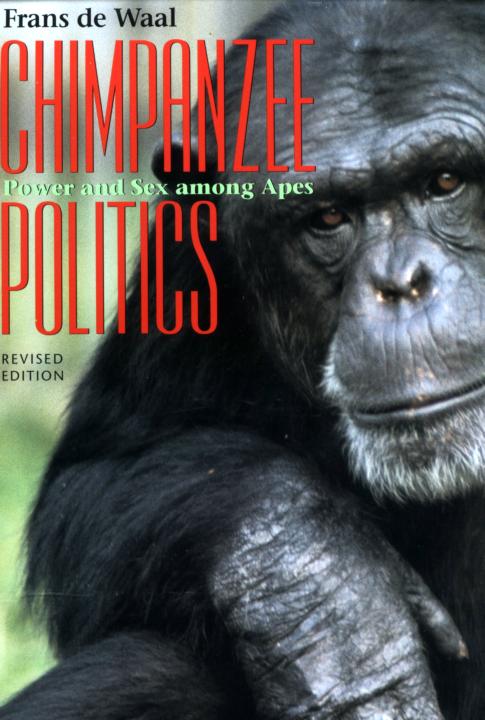

WHEN I WROTE CHIMPANZEE POLITICS, IN 1979 AND 1980, I WAS A beginning scientist, in my early thirties, without much to lose. At least, that's the way I looked at it at the time. I didn't mind following my intuitions and convictions, however controversial these might be. Keep in mind that this was a time at which the words animal and cognition could barely be mentioned in the same sentence without raising eyebrows. Most of my colleagues shied away from the suggestion of intentions and emotions in animals for fear of being accused of anthropomorphism. Not that they necessarily denied animals an inner life, but they followed the behaviorist dogma that, since what animals think and feel is unknowable, there is no point in talking about it. I still remember standing for hours on the metal grid over the smelly night quarters of the chimpanzees, holding the only phone in the building to my ear, talking with my professor, Jan van Hooff, who, though always supportive, was also quite a bit more cautious than I, trying to convince him of yet another wild speculation. It is during these discussions that Jan and I, at first jokingly, began referring to developments in the colony as "politics."

The other major influence on this book was the general public. For years, I addressed organized groups of zoo visitors, including lawyers, housewives, university students, psychotherapists, police academies, bird-watchers, and so on. There is no better sounding-board for a wouldbe popularizer. The visitors would yawn at some of the hottest academic issues, but react with recognition and fascination to basic chimpanzee psychology that I had begun to take for granted.

I learned that the only way to tell my story was to bring the chimpanzee personalities to life and to pay attention to actual events rather than the abstractions that scientists are so fond of. I benefited greatly from a previous experience. Before I came to Arnhem, I had done a dissertation project at the University of Utrecht. In one of my monkey groups, the males had changed ranks, resulting in my very first scientific paper, published in 1975, entitled: The wounded leader: A spontaneous temporary change in the structure of agonistic relations among captive lava-monkeys. In putting this report together, I had noticed how utterly useless the cus tomary formalized records of ethologists are when it comes to social drama and intrigue. Our standard data collection aims at categorizations that serve the counting of events. Computer programs sort through the data, creating neat summaries of aggressive incidents, grooming bouts, or whatever behavior we are interested in.

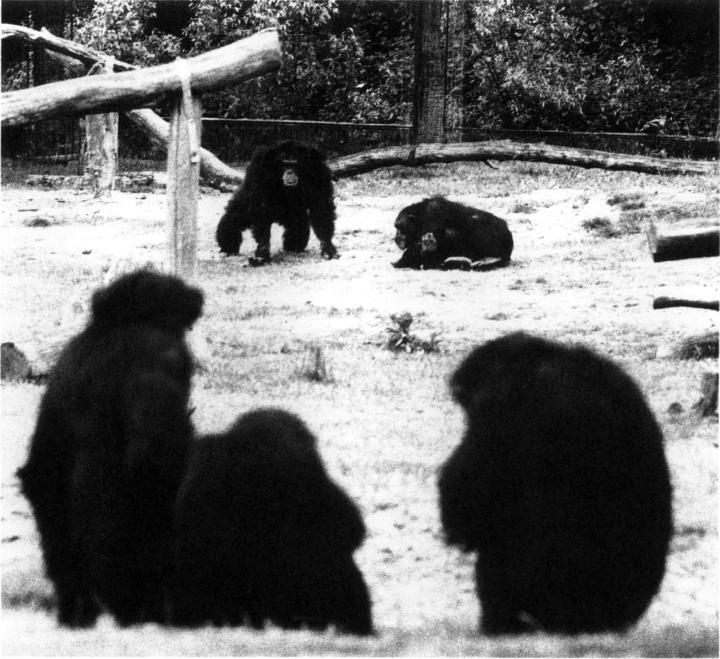

My eyes were not the only ones riveted on the drama in the colony: the apes, themselves, kept a close watch as well. A few of them look on while Nikkie (background, left) is waking up Yeroen with an intimidation display.

Items that cannot be quantified and graphed run the risk of being tossed aside as mere "anecdotes." Anecdotes are unique events from which it is hard to generalize. But does this justify the contempt in which some scientists hold them? Let's consider a human example: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein describe in The Final Days Richard Nixon's reaction to his loss of power: "Between sobs, Nixon was plaintive.... How had a simple burglary done all this? ... (He) got down on his knees ... leaned over and struck his fist on the carpet, crying aloud, `What have I done? What has happened?"'

Nixon was the first and only U.S. president to resign, so this really can't be much else than an anecdote. But does this diminish the observation's significance? I must admit to a great weakness for rare and peculiar events. As we shall see, one of my chimpanzees had tantrums similar to Nixon's (minus the words) under similar conditions. I learned from my earlier study that in order to analyze and understand such events one needs a diary that conveys how things unfolded, how each individual got involved, and what was special about a situation compared to previous ones. Instead of merely counting up and averaging chimpanzee behavior, I was intent on injecting historiography into my project.

Thus, upon arrival in Arnhem I opened a diary. Since little happened initially, I filled it with notes about personalities and behavior patterns that struck me as unusual. As a result, however, I was getting into a chronicling mode, sensitive to shifting social relationships, ready for the political drama that was to come. When at last it did explode, I filled page after page with impressions, predictions, corrections of earlier impressions, but most of all the bare facts. Fascinated and emotionally engaged, I spent day-in-day-out and thousands of hours on a wooden stool overlooking the island, intent on producing the most detailed record ever of a power struggle, human or nonhuman. It is only in sifting through my copious notes, years later, that the connections between various events fell into place, and Chimpanzee Politics began to take shape.

The book caused little controversy when it first appeared, in 1982, with the publishing house of Jonathan Cape, in London. In both popular and academic reviews it was welcomed rather than attacked. In hindsight, this is understandable as its underlying premise perfectly fit the Zeitgeist of the 198os in which attitudes toward animals were rapidly changing. Having worked largely in isolation from the emergence of cognitive psychology in America, I had not realized that I had not been alone in the exploration of this new intellectual territory. This circumstance illustrates how scientific developments in different corners of the world are often connected by thin threads of shared ideas. They are never totally independent. Thus, Donald Griffin's The Question of Animal Awareness did not surprise me when I first read it, just as Chimpanzee Politics evidently did not surprise most primatologists.

If we follow Harold Laswell's famous definition of politics as a social process determining "who gets what, when, and how," there can be little doubt that chimpanzees engage in it. Since in both humans and their closest relatives the process involves bluff, coalitions, and isolation tactics, a common terminology is warranted. The title of my book drove this point home. Whereas several political scientists had no objections, one among them felt a need to delineate humans as quite different.' As so often in the history of ape-human comparisons, ad hoc changes were made in the definition of a phenomenon so as to exclude the primate data. At a symposium on the application of political theory to animals, Glendon Schubert proposed that the term "politics" be reserved for processes within groups of at least one hundred individuals without kinship ties. This obviously excluded most social animals, as well as many situations in which humans play power games.