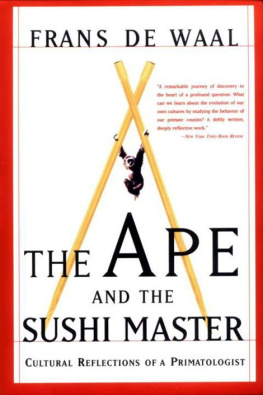

Man is innately programmed in such a way that he needs a culture to complete him. Culture is not an alternative or replacement for instinct, but its outgrowth and supplement.

J o Mendi, a cigar-smoking, brandy-drinking blue-collar worker with stocky legs and long arms, was used to having his name larger on the billboards than that of comedian Bob Hope, with whom he once co-starred. In the 1930s, he dominated Detroits entertainment industry. Every day, he would show up in overalls at the side of the zoo director, who carried a cane and kept a watchful eye on his companion, whobeing many times stronger than a grown manhad been known to molest unsuspecting bystanders. Such was Jo Mendis fame that the chimpanzee drew a crowd twice as large as the one that greeted the presidential candidate visiting the city, an issue Franklin Delano Roosevelts opponents didnt hesitate to bring to the nations attention.

Jo Mendi showing his table manners with zoo director, John Millen, in the 1930s (Photo courtesy of the Detroit Zoological Society).

Petermann, a performing chimpanzee at the Cologne Zoo in the 1980s, was less lucky. Like Jo Mendi, he had a huge following and was, behind the scenes, not to be trifled with. His relationship with the zoo director was less amicable, however. After attacking the director, Petermann was shot by the police. His fatal defiance of authority temporarily turned the ape into a martyr for the German anarchist movement.

Even today, Hollywood producers cannot resist throwing in a chimp or orangutan when their script asks for a laugh and they have failed to come up with anything better. An entire television show (The Chimp Channel) has been devoted to dressed-up apes trained to frantically move their mouths while an audio track with human speech gives the impression that they are talking.

The ape dinner parties that became standard at zoos and menageries in the nineteenth century, the chimpanzee entertainers of the twentieth century, and contemporary equivalents on the tube all project the image of animals doing their best to be like us, yet failing miserably. We get a kick out of such performances because our culture and dominant religion have tied human dignity and self-worth to our separation from nature and distinctness from other animals. Since we are the only ones who eat with cutlerya sure sign of civilizationwe are amused to see apes trying to do the same. Theyre not supposed to, and most certainly theyre not supposed to be good at it. Lest the scene threaten the human ego, they must falter. As explained by Ramona and Desmond Morris:

In the late 1920s the London Zoo started to organize these demonstrations on a regular basis. Each afternoon at a set time a group of young chimpanzees performed at a table

To have apes ridicule our species, especially the cultural refinements that we admire so greatly in ourselves, could be looked at as a form of self-deprecation. That would be the optimistic view. The alternative is that by allowing animals to mock us we let them make even greater fools of themselves, which permits us to laugh away any doubts we might harbor about ourselves. That we select apes for this job is logical because it is particularly in the face of animals similar to us that human uniqueness needs confirmation.

To put this in perspective, imagine a family of elephants watching a television show in which people have hoses strapped to their noses and try to use the appendage to pick up a coin or uproot a small tree. The poor people in the show constantly get tangled up in their trunks, trip over them, and in general demonstrate how ineptly unelephantine they are. I dont think we would find the show particularly funny, certainly not for longer than a couple of minutes, but an elephant family might never get enough of it.

Theyre getting restless. Okay boys, ham it up knock the teapot over or something. (Cartoon of ape tea party at the zoo by Paul White, in 1962, reproduced with permission of Punch Ltd.)

This is because the issue is not humor, but self-definition.

Culture Versus Nature?

We define ourselves as the only cultured species, and we generally believe that culture has permitted us to break away from nature. We are wont to say that culture is what makes us human. The sight of apes with wigs and sunglasses acting as if they have made the same step is therefore utterly incongruous. But what if apes have made this step to cultured behavior not only for the entertainment of the human masses, but also in real life without our assistance? What if they have their own culture rather than a superficially imposed human version? They might not be so amusing anymore. Indeed, even to contemplate such a possibility is bound to shake centuries-old convictions.

The possiblility that animals have culture is the topic I wish to explore in this book. Although such an exploration is worthwhile for a number of reasons, two stand out. First, there is growing evidence for animal culturemost of it hidden in field notes and technical reportsthat deserves to be more widely known. Before we can consider this material, however, we need to temporarily abandon a few cherished connotations of the term culture. This term evokes images of art and classical music, symbols and language, and a heritage that needs protection against the mass-consumption society. A so-called cultured person has achieved a refinement of tastes, a well-developed intellect, and a particular set of values and moral principles. This is not how scientists use culture in relation to animals. Culture simply means that knowledge and habits are