Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Sue, always

What is this thing of whiteness?

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

i

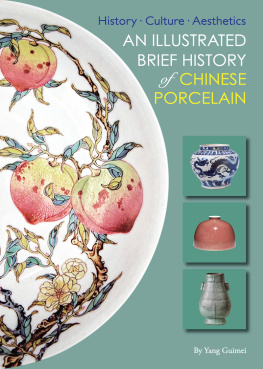

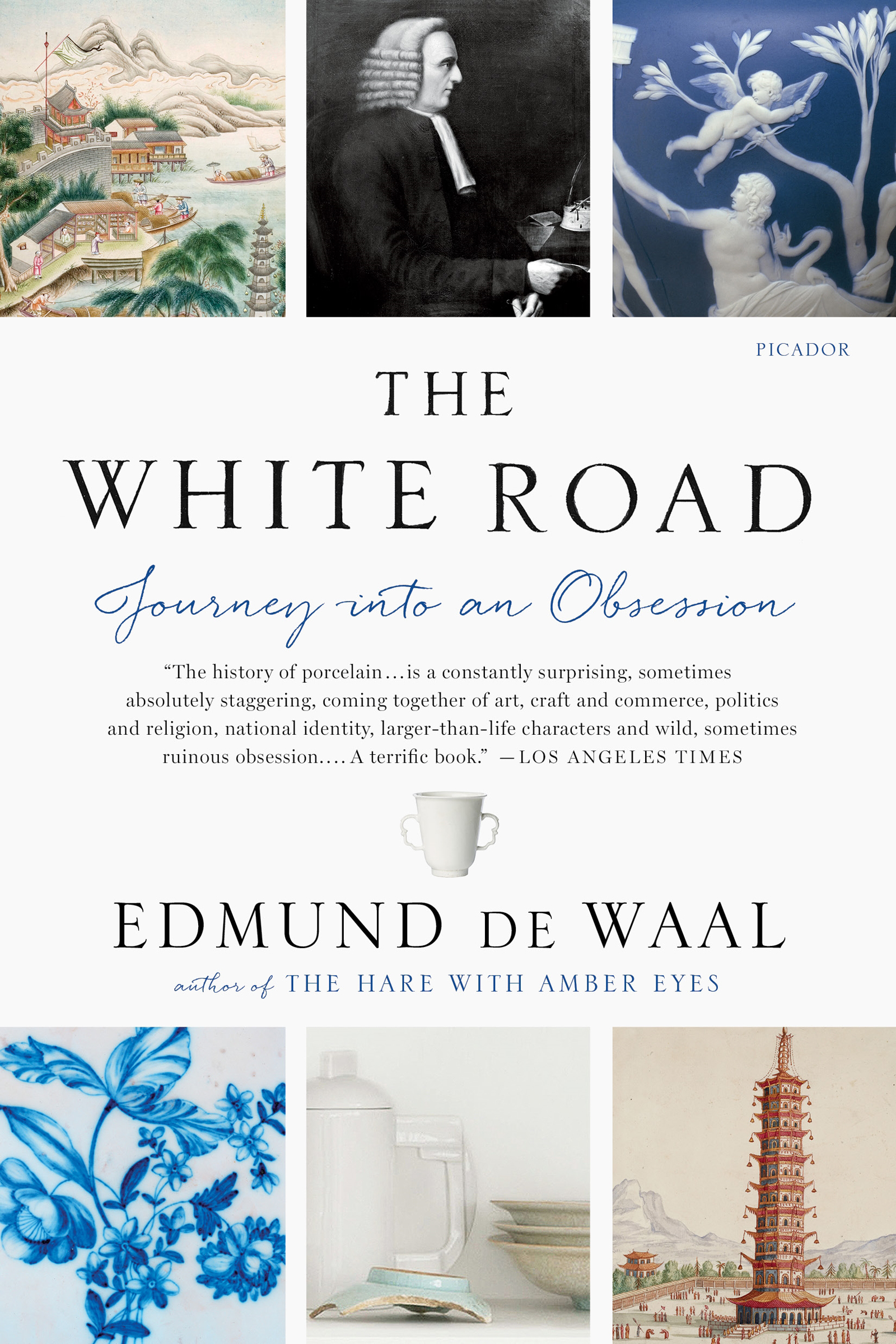

Im in China. Im trying to cross a road in Jingdezhen in Jiangxi Province, the city of porcelain, the fabled Ur where it all starts; kiln chimneys burning all night, the city like one furnace with many vent holes of flame, factories for the imperial household, the place in the fold of the mountains where my compass points. This is the place where emperors sent emissaries with orders for impossibly deep porcelain basins for carp for a palace, stem cups for rituals, tens of thousands of bowls for their households. It is the place of merchants with orders for platters for feasts for Timurind princes, for dishes for ablutions for sheikhs, for dinner services for queens. It is the city of secrets, a millennium of skills, fifty generations of digging and cleaning and mixing white earth, making and knowing porcelain, full of workshops, potters, glazers and decorators, merchants, hustlers and spies.

It is eleven at night and humid and the city is neon and traffic like Manhattan and a light summer rain is falling and Im not completely sure which way my lodgings are.

Ive written them down as Next to Porcelain Factory #2 and I thought I could pronounce this in Mandarin, but Im met with busy incomprehension, and a man is trying to sell me turtles, jaws bound in twine. I dont want his turtles, but he knows I do.

It feels absurd to be this far from home. There is televised mah-jong at high volume in the parlours with their glitter balls like a 1970s disco. The noodle shops are still full. A child is crying, holding her fathers finger as they walk along. Everyone has an umbrella but me. A barrow of porcelain models of cats is wheeled past under a plastic tarp, scooters weaving round it. Ridiculously someone is playing Tosca very loudly. I know one person in the whole city.

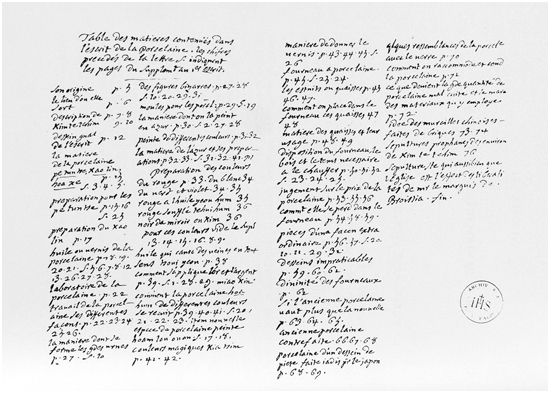

I havent got a map. I do have my stapled photocopy of the letters of Pre dEntrecolles, a French Jesuit priest who lived here 300 years ago and who wrote vivid descriptions of how porcelain was made. Ive brought them because I thought he could be my guide. At this moment this seems a slightly affected move, and not clever at all.

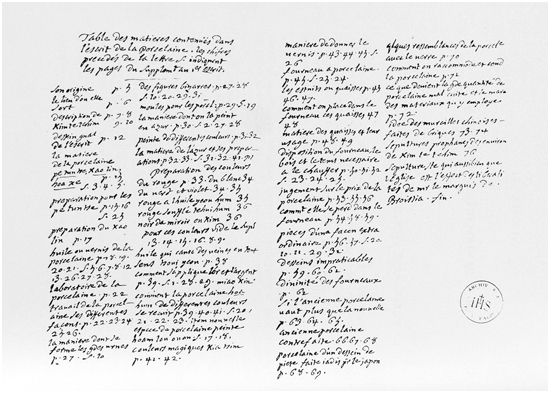

Pages from Pre dEntrecolles letters on Chinese porcelain, 1722

Im sure Im going to die crossing this road.

But I know why Im here, so that even if Im not sure which way to go, Ill go confidently. It is really quite simple, a pilgrimage of sorts a chance to walk up the mountain where the white earth comes from. In a few years I am turning fifty. Ive been making white pots for a good forty years, porcelain for twenty-five. I have a plan to get to three places where porcelain was invented, or reinvented, three white hills in China and Germany and England. Each of them matters to me. I have known of them for decades from pots and books and stories but I have never visited. I need to get to these places, need to see how porcelain looks under different skies, how white changes with the weather. Other things in the world are white but, for me, porcelain comes first.

This journey is a paying of dues to those that have gone before.

ii

A paying of dues sounds appallingly pious but it isnt.

It is a lived truth, a bit declamatory, but a truth none the less. If you make things out of porcelain clay, you exist in the present moment. My porcelain comes from Limoges in the Limousin region of France, halfway down on the West. It comes in twenty-kilo plastic bags, each bag with two ten-kilo sausages of perfectly blended porcelain clay, the colour of full-fat milk, with a bloom of green mould. I unwrap one and thump it down on to my wedging bench, pull the twisted wire through a third of the way along, pick up the lump and push it into the bench, raising it and pushing it down in a circular motion, like kneading dough. It gets softer as I do this. I slow down and the clay becomes a sphere.

My wheel is American and silent and low to the ground, jammed up against the wall in the middle of the slightly chaotic studio. I look at the white brick wall. There are too many people in this small space, two full-time and two part-time assistants to help with glazing and firing and logistics and the deluge of mail from my last book. There is too much noise from the neighbours. I need another studio. Things are going well. I have just been invited to show in New York and I have a dream of walking through an expansive gallery, full of light, walking far away from a piece of my work, turning around and seeing it with new eyes, alone, seeing it as if for the first time. Here I stretch my long arms and touch packing crates. I can get fifteen feet away. On a good day.

Everyone is being as quiet as they can but, damn it, the concrete floor is noisy. There is an argument outside. I need to make time to be nice to estate agents again as getting a studio is difficult in London. All those useful bits of space where people used to make things or mend them round the backs of house are being developed for apartments. I need to talk to the accountant.

I sit at my wheel.

And I throw the ball of clay into the centre, wet my hands and I am making a jar now and pulling the clay up with the knuckle of my right hand on the outside, three fingers of my left tensed inside to support, as the walls grow taller and the volume changes like an exhalation, something being said. Im in this moment while also being elsewhere. Altogether elsewhere. Because the clay is the present tense and a historical present. Im here in Tulse Hill, just off the South Circular road in South London, in my studio behind a row of chicken takeaways and a betting shop, sandwiched between some upholsterers and a kitchen-joinery workshop, and as I make this jar Im in China. Porcelain is China. Porcelain is the journey to China.

It is the same when picking up this Chinese porcelain bowl from the twelfth century. The bowl was made in Jingdezhen, thrown then moulded with a flower in a deep well, unglazed rim, green-grey with a slightly pooled glaze, some issues as the dealers would say, chips, marks, scuffs. It happens in the present tense and it is, itself, a continuous present of active, dynamic movements, judgements and decisions. It doesnt feel in the past, and it feels wrong to force it into one just to obey a critical orthodoxy. This bowl was made by someone I didnt know, in conditions that I can only imagine, for functions that I may have got wrong.

But the act of reimagining it by picking it up is an act of remaking.

This can happen because porcelain is so plastic. Pinch a walnut-sized piece between thumb and forefingers until it is as thin as paper, until the whorls of your fingers emerge. Keep pinching. It feels endless. You feel it will get thinner and thinner until it is as thin as gold leaf and lifts into the air. And it feels clean. Your hands feel cleaner after you have used it. It feels white. By which I mean it is full of anticipation, of possibility. It is a material that records every movement of thinking, every change of thought.