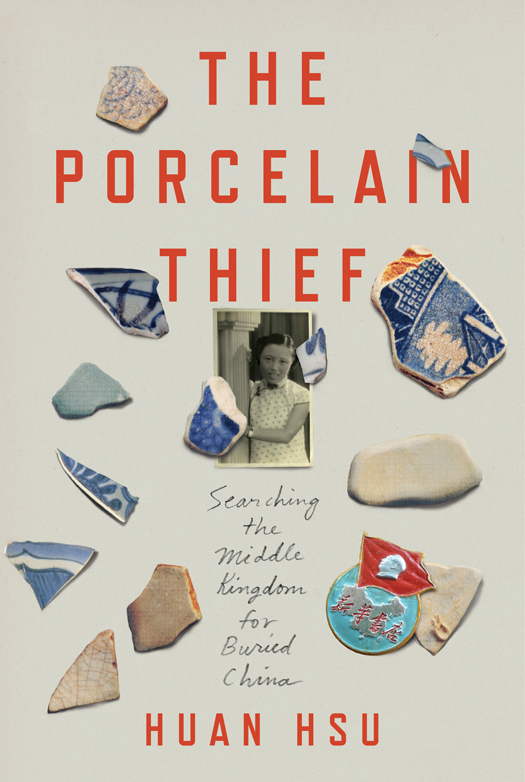

Copyright 2015 by Huan Hsu

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hsu, Huan.

The porcelain thief : searching the Middle Kingdom for buried China /

Huan Hsu. First edition.

1. Hsu, HuanFamily. 2. Hsu, HuanTravelChina. 3. Chinese AmericansEthnic identity. 4. Chinese AmericansTravelChina. 5. Jiujiang Region (Jiangxi Sheng, China)Biography. 6. Treasure trovesChinaJiujiang Region (Jiangxi Sheng) 7. Porcelain, ChineseHistory. 8. ChinaDescription and travel. 9. ChinaHistory19th century. 10. ChinaHistory20th century.

I. Title.

E184.C5H83 2015

305.8951073dc23 2014037872

ISBN 978-0-307-98630-6

eBook ISBN 978-0-307-98631-3

Maps by Jeffrey L. Ward

Cover design by Na Kim

Cover photographs (porcelain shards): Jonathan Blair / National Geographic Creative; Lyn Randle / Getty Images

v3.1_r1

To my family,

the treasure I always had,

and to Jennifer,

the treasure I never expected to find

Contents

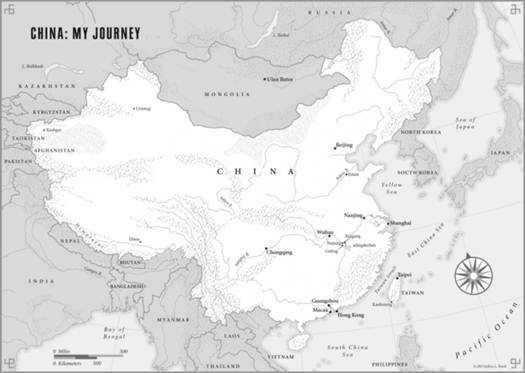

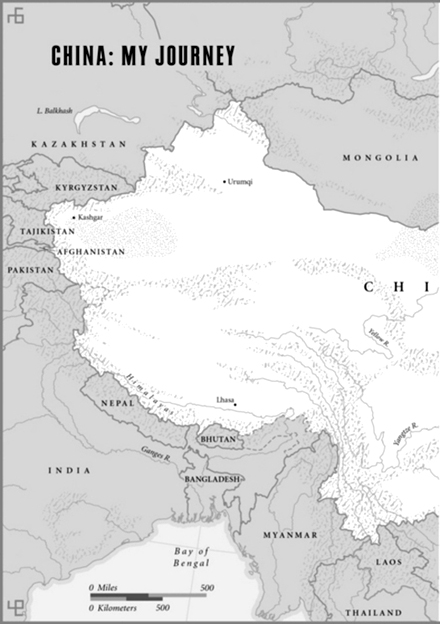

T HIS BOOK RECOUNTS MY TIME IN C HINA FROM 2007 TO 2010 , and then the summer and fall of 2011. Although this is a work of non-fiction, any attempt to reconstruct recent history is inherently subjective, and my guiding principle was to tell a coherent story about China, my family, and my search for my great-great-grandfathers buried porcelain. Many of the people and places in this book were visited a number of times over many years. For the sake of narrative logic, I have in some instances compressed the time between these encounters, omitted extraneous details, or explained information out of time with its revelation to me. However, descriptions of people, places, or encounters themselves have not been altered, and the dialogue was recorded either as it happened or soon thereafter.

A word on translations: Many of my conversations with Chinese speakers took place in Mandarin Chinese. When translating the conversations, I tried to be faithful to my partners intended meaning and re-create it as I understood it in everyday English while also preserving the unique qualities of their speech. The instances where Chinese speakers use English are noted as such. I have used pinyin transliterations except for names commonly spelled otherwise, such as Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen, and the members of my family who write their names according to Wade-Giles conventions.

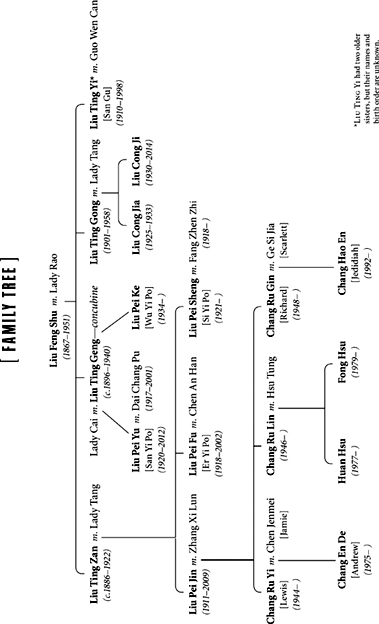

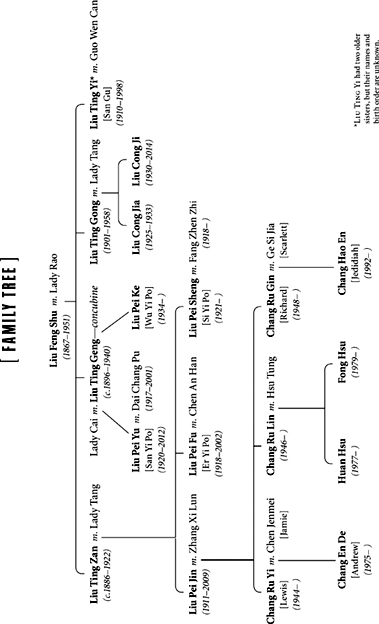

Chinese kinship terms are manifold and complicated; depending on the relationship, each family member has a unique term by which they are called. I have simplified this by referring to characters either by their given names or according to their relationship to me, except for San Gu, my grandmothers aunt. Full Chinese names are written with the surname first, followed by the given name.

Finally, all dates have been converted from the lunar calendar to the Gregorian calendar. And the conversion rate for Chinese RMB to U.S. dollars for this book is 7:1.

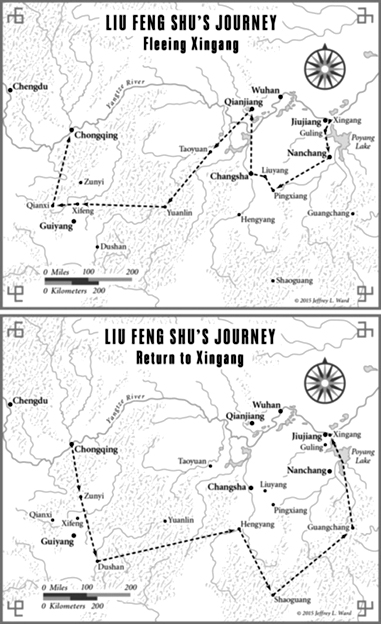

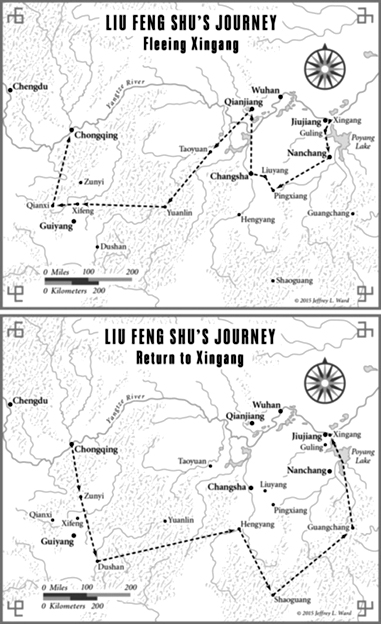

T HE FIRST SIGN OF TROUBLE CAME IN THE SPRING OF 1938. On the tails of the snow cranes leaving their wintering grounds in the Poyang Lake estuary, Japanese planes appeared in the sky, tracing confused circles as if they had lost their flock. It soon became clear that these reconnaissance planes were not stragglers but the vanguard for another kind of migration. After taking Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing, the Japanese army advanced through China not like a spreading pool of water but like a gloved hand, and in the summer of 1938 its middle finger traced up the Yangtze River toward my great-great-grandfather Liu Feng Shus village of Xingang.

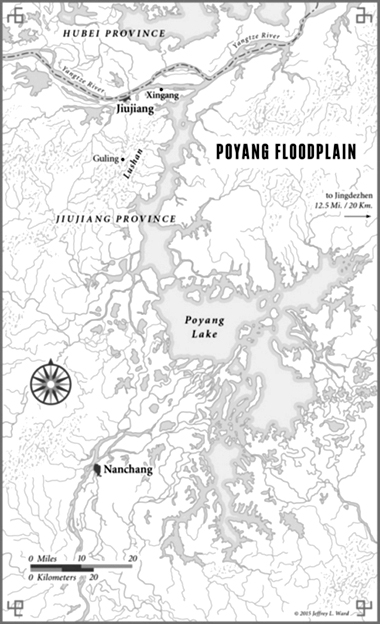

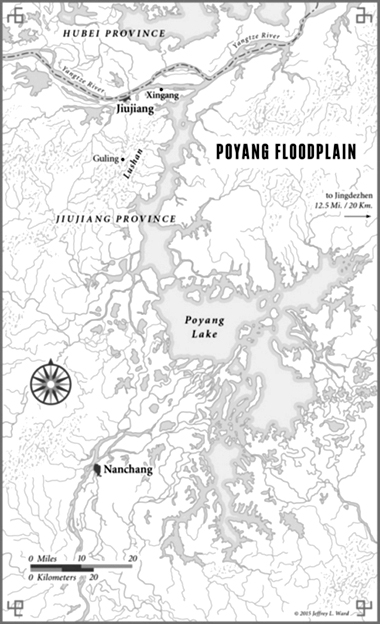

Liu presided over one of the most prominent families in Xingang, situated on a spit separating the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake, Chinas largest freshwater body, like a valve. His estate included most of the arable land along the river, worked by a small army of sharecroppers, and a number of residences at the western edge of the village, the largest being his own. Guarded by a trio of stately pine trees, the sprawling stone abode fronted the road heading into the nearby city of Jiujiang, a major trading and customs port. There lived a coterie of daughters-in-law, grandchildren, and servants; the eldest of Lius three sons, my great-grandfather, died of tuberculosis in his thirties, and his school-aged children, as well as those of Lius surviving sons, lived with him while their fathers worked elsewhere in the province, a common arrangement in Chinese families. My great-great-grandfather filled the rooms with objets dart befitting a scholar who had passed the imperial civil service exam, including his prized collection of antique porcelain. Accumulated by the crate, some of the items dated back hundreds of years to the Ming dynasty and had once belonged to emperors, and for all my great-great-grandfathers other forms of wealth, these heirlooms, as enduring as they were exquisite, best represented the apogee of both family and country. Across the road, beyond the communal fishpond, dug into a hill that gathered the setting sun, was the cemetery where eleven generations of his ancestors kept watch over his prosperity.

As the summer went on, phalanxes of Japanese bombers soared over Lius fields to drop ordnance on westerly cities, unencumbered by a Chinese army with pitiful air defenses. According to the newspapers that Liu picked up in the mornings from the general store down the road, Republic of China president Chiang Kai-shek was prepared to stage a vicious defense of Jiujiang and had nearly one million troops dug in along the Yangtze. The presence of Chinese soldiers became a regular sight in Xingang, if not a welcome one, given the Nationalist armys reputation for incompetence and venality.