Ive been spending time in archives again. It is an early-spring morning and there is that barely suppressed immanence in the trees in the park. Few leaves yet but next week will be different. Too cold and wet to sit for long on one of the benches, but I do. Even the dogs arent hanging about. Its been raining. There is a word for the smell of the world after rain: petrichor. It sounds a little French.

Everyone seems to be off and away at this hour. All this forward energy, propulsive.

I get up and walk along the damp gravelled path, out of the great gilded gates into the avenue Ruysdal and turn left up the rue de Monceau. I ring the buzzer outside number 63 and wait for a response.

Im going back to archives. That strong pull up to those rooms high in the attics, the servants quarters, going back a hundred years.

Dear friend,

I am making an archive of your archive.

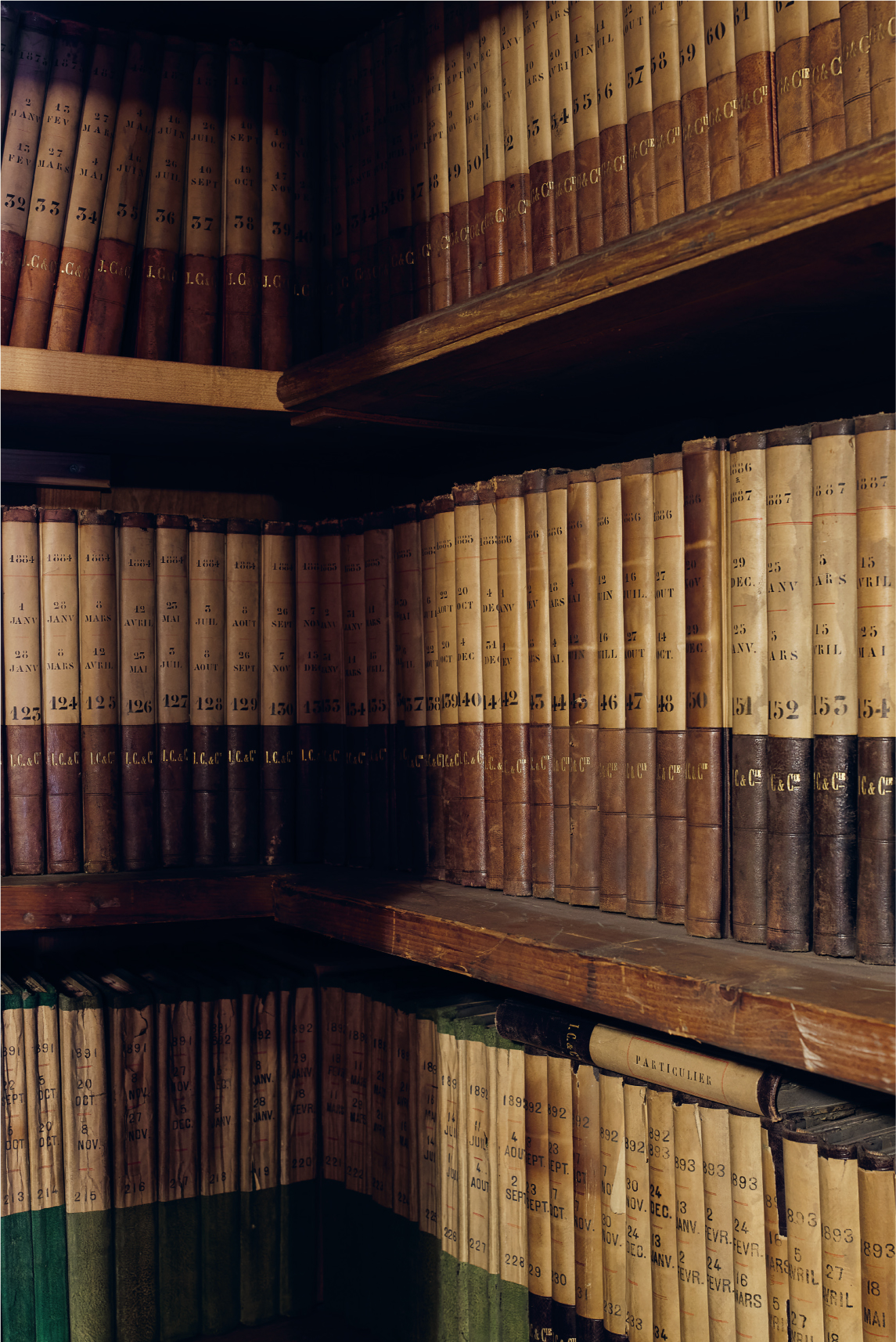

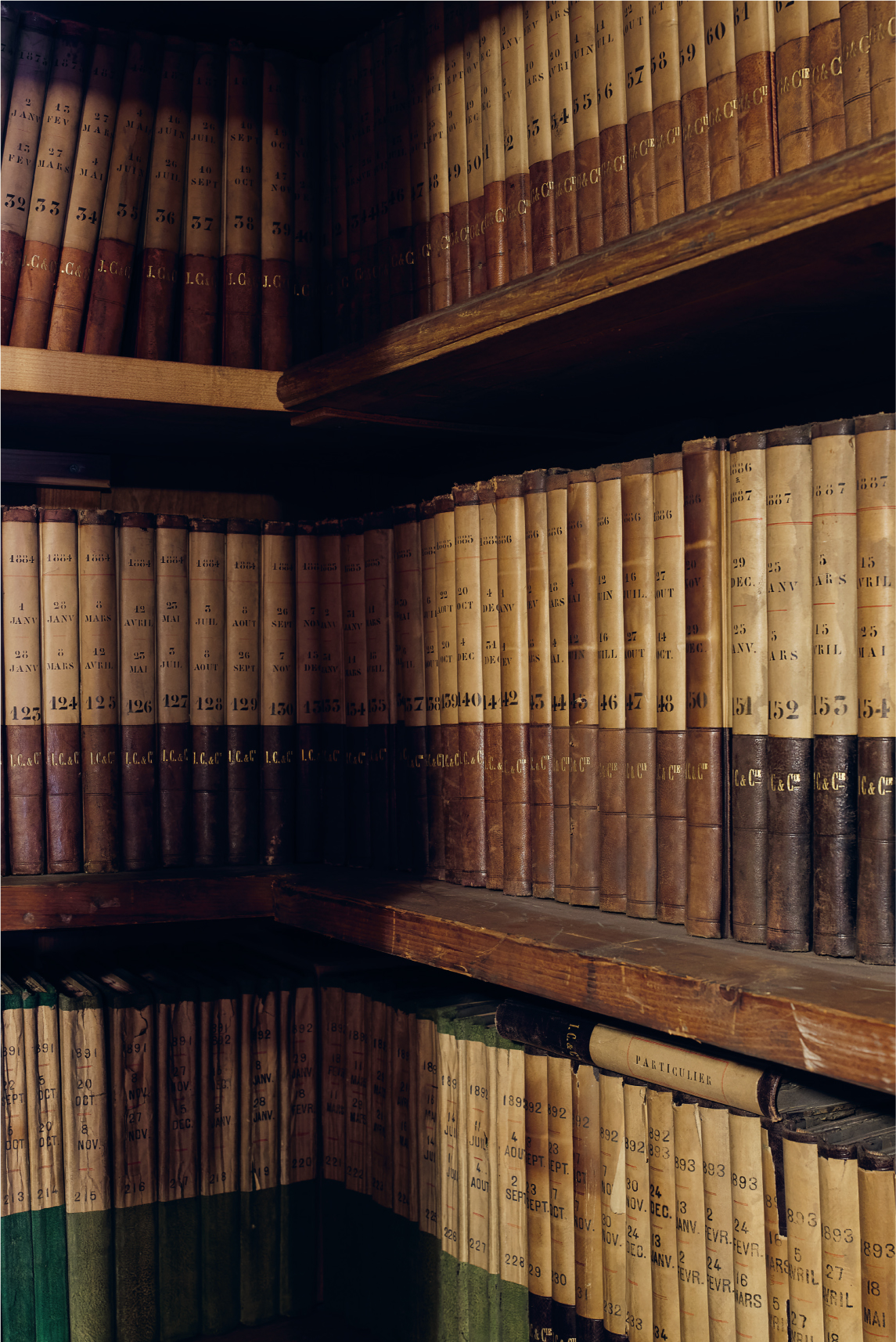

I find inventories, carbon copies, auction catalogues, receipts and invoices, memoranda, wills and testaments, telegrams, newspaper announcements, cards of condolence, seating plans and menus, scores, opera programmes, sketches, bank records, hunting notebooks, photographs of artworks, photographs of the family, photographs of gravestones, account books, notebooks of acquisitions.

Each document is on a different kind of paper. Each has a different weight and texture and scent. Some have been stamped to show when a letter has been received and when answered. Archives are a way of showing how conscientious you are and it is clear that this is a place of discreet and powerful concentration.

Why is so much copied? Why carbon copies, almost weightless?

Here on the fifth floor of 63 rue de Monceau amongst the servants rooms is a room lined with deep oak-panelled cupboards. It used to be lancien garde-meubles, the old storage room, according to the architects plans from 1910. Each cupboard is full of ledgers and volumes of letters and boxes of photographs. Some ledgers are double-stacked. It is a whole world. It is a family, a bank, a dynasty.

I want to ask if you ever threw anything away.

I find the letters about excursions to restaurants with gastronomic friends. I find instructions to the gardeners for the annual replanting of the parterre, instructions to your wine merchant, to the bookbinder to keep your copies of the Gazette des beaux-arts in perfect red morocco, instructions for the storage of furs, instructions for the vet, the cooper, the florist. I find your responses to the dealers who write, daily.

Here are your notebooks of purchases. The first inscribed Before 1907 22 Novembre 1926. Second one 3 Janvier 1927 2 Aot 1935. They are meticulous.

I find manifests for cargo, manifests for people as cargo.

I find the manifests for your daughter. For your son-in-law. For their children.

I find this difficult.

Dear friend,

As I am mostly English I want to ask you about the weather.

I want to enquire about the weather in Constantinople and out in the Halatte Forest where you hunt with the Lyons-Halatte in blue livery at the weekends and at Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat and out at sea. Gusty. I know that you had a rather splendid yacht but Im not sure if that was a plutocratic purchase of obligation or pleasure. In fact, I want to know more about your obsession with speed. All that bowling along in the newest motor car with the wind buffeting you, the Paris to Berlin race, everything flying past as France disappears into the dust made by your Renault Landaulet. In 1895 you sit high up in a cap and goggles and a leather motoring coat, a blanket over your knees, and you are ready to take on the world. It is a sunny day. The shadows of the car are long. The road is empty.

I wonder about the weather in the paintings by Guardi that you have bought for le petit bureau, the small study. The gondoliers are straining against the wind past the Piazza San Marco. The pennants are flying. The lagoon is an empyrean jade.

I want to know about the porcelain room where your Svres services, les services aux oiseaux Buffon, are displayed in cabinets, on six shelves, and where you eat your lunch alone do you look out of the window and see the branches of the trees swaying gently in your garden and beyond it in the Parc Monceau? In 1913, you planted acer, Chinese privet and deep-red-leaved Prunus cerasifera Pissardii, cherry plum trees. You were thinking ahead, of course.

This is how the English ask how you are. We talk about the weather. And trees.

Ill ask again.

Dear

I realise that Im not entirely sure about how to address you, Monsieur le Comte.

As I shuffle through the letters from the dealers and the tradesmen soliciting your attention, your patronage in the matter of the anniversary exposition, your kindness in allowing us to remit this bill, you are addressed in various orotund ways. I like the collegiate greeting I found this morning from a friend from the Club des Cent inviting you to join him on a gastronomic adventure in a private restaurant car: Mon cher Camarade.

In these things I am caught between not wanting to offend and not wanting to waste time. Monsieur is possible and dignified and might lead to Cher Monsieur.

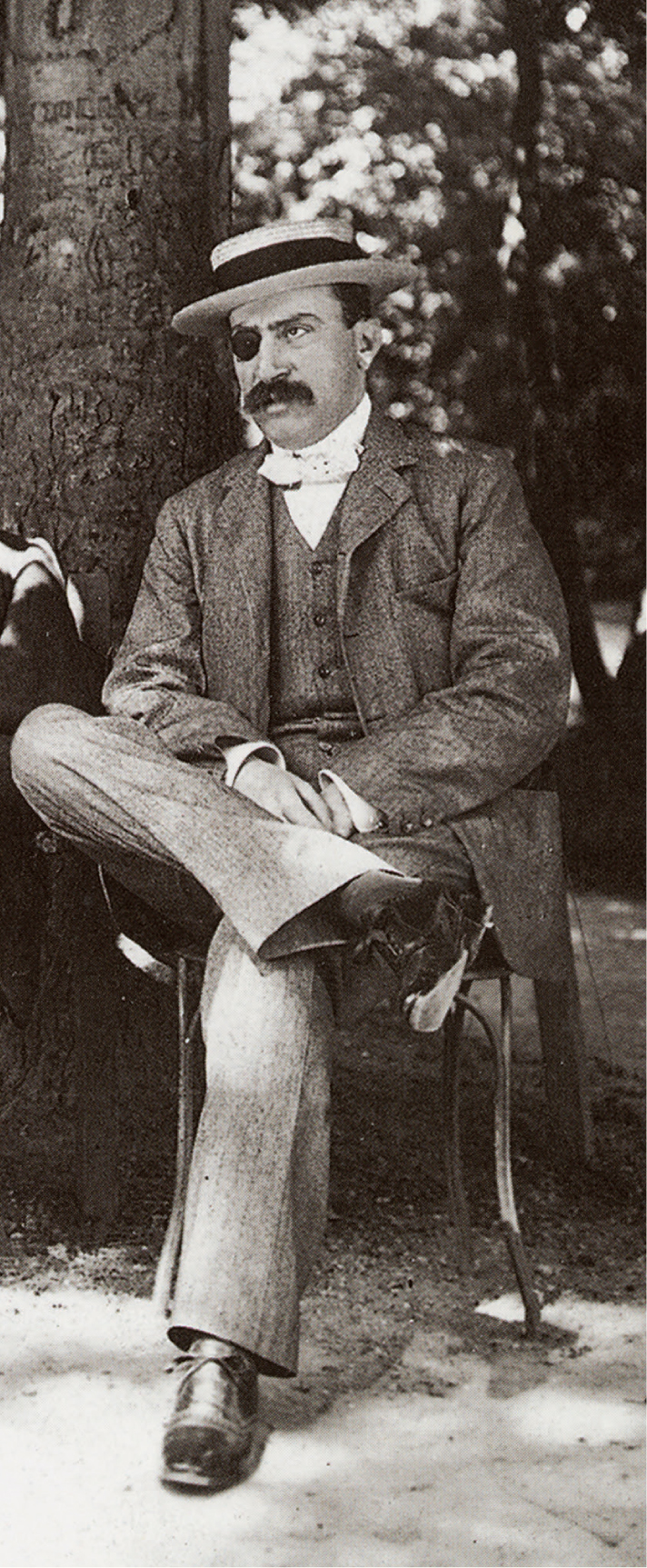

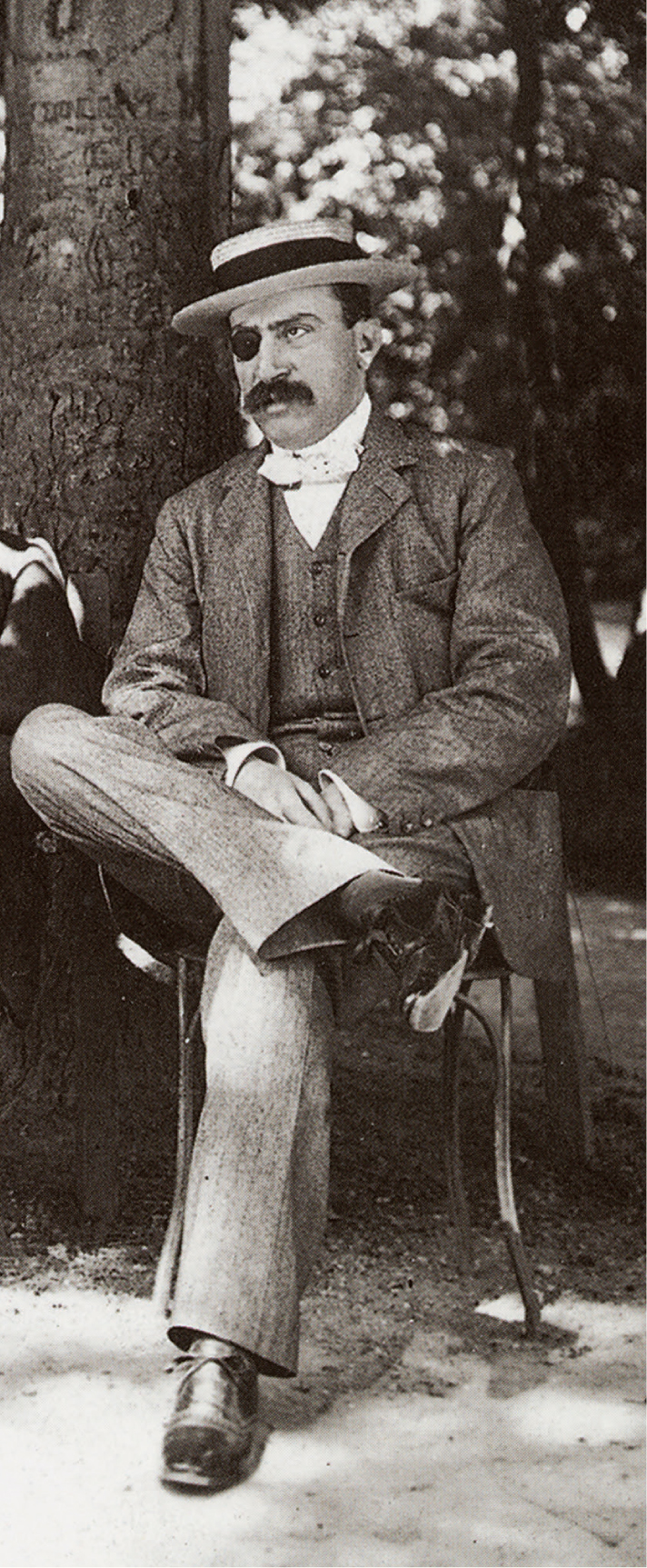

So I am not going to call you Mose. And to call you Camondo sounds stentorian, a barked greeting across a library or dinner table. I know we are related in complicated ways but that can wait. So I am writing to you as friend.

We shall see how we get on.

I feel strange about signing off too

Dear friend,

Id like to ask you about the carpet of the winds. It is in le grand salon, the large drawing room, overlooking the park.

It is one of ninety-three carpets woven at the Savonnerie manufactory between 1671 and 1688 for the Galerie du Bord de lEau in the Louvre. This is the fiftieth. The four winds puff their cheeks and blow their long horns and the air is knotted and ravelled with gusts of ribbons and Juno and Aeolus. There are crowns and more trumpets and cascades of flowers deliquescing and stiff acanthus framing it all and it is gold and blue; the colour of the wind along the wharfs of Galata, out at sea. This is early-morning stuff, bracing.

It used to be a longer carpet when you first walked on it in the house of the Heimendahls fellow financiers in the rue de Constantine, and when they were in some financial embarrassment you bought it from them. Im pleased to find that Charles Ephrussi helped you buy it as he knew you and them, knew everyone, could deal with this sort of thing, charmingly, and made things happen. Charles is important to me, the cousin who set me off on my adventures.