For Nowera, your love and faith and strength have kept us as one, despite hard times.

For Lou and Debby, who opened the doors between Stany and David.

And thanks be to God for the miraculous outworking of His plans.

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has called on scientists, caregivers, and conservationists to stop publishing material that depicts humans in close contact with nonhuman primates. Stany and David wholeheartedly support these sentiments. Stany is a chimp specialist, and he only ever interacts with chimps in a manner that benefits them. Chimpanzees are dangerous, and Stanys behavior should not be copied or emulated in any way. Stany and David will never knowingly support any organization or individual that treats apes as pets or in a manner that is not in their best interests or true to their species.

FOREWORD

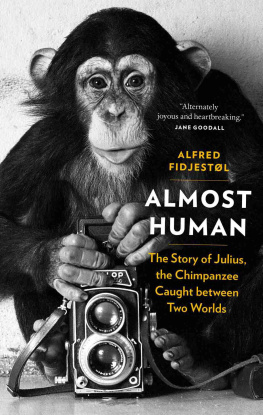

It was in 1960, more than a half century ago, that I began my study of chimpanzees in the forested mountains above the shores of Lake Tanganyika at the Gombe National Park. Even back then we knew a good deal about the similarities in behavior between humans and chimpanzees. But now, following long-term studies at Gombe and other field sites, we know a great deal more. We understand the strength of the enduring family bonds between mothers and offspring and between siblings that can last a life of more than sixty years. We know that chimpanzees, like ourselves, are capable of violence and brutality as well as love, compassion, and altruism. Through advances in science, we now know more about the biological similarities in the immune system, composition of blood, and the structure of the brain. We have learned that the DNA of humans and chimpanzees differs by just a little over 1 percent. The primates we call chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes, are the closest surviving relatives of the primates we call humans, Homo sapiens.

I loved working in the forests of Gombe, but I left to try to help efforts to conserve chimpanzees and their habitats. Their forests are being destroyed. They are hunted both for the live animal trade that captures the infants (by killing the mother) to sell to zoos or as pets, and for the bushmeat trade, the commercial shooting of wild animals, including chimpanzees, for food. When mother apes are killed for this trade, their traumatized infants are often sold in the markets as pets. Then they need our help.

When people think of the champions of African wildlife, the names that spring to mind are usually Dian Fossey, George Schaller, David Attenborough, Iain Douglas-Hamilton, and othersAmericans and Europeans. But there are an increasing number of true champions of wildlife among the African people as well. These include park wardens who resist rampant corruption and game rangers who risk and too often lose their lives in the fight against poaching.

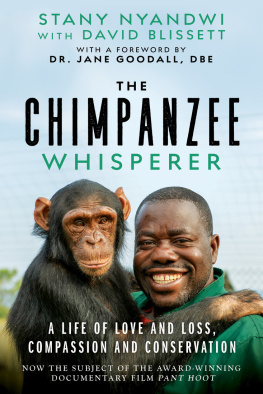

This book tells the story of one of these inspiring protectors of African animals, Stany Nyandwi. From the time he first joined the staff of the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), Stany has taken up the chimpanzees cause. He has helped look after the orphaned chimpanzees in our care, and it almost cost him his life. He has endured untold hardships and personal sacrifice to care for these animals threatened by human wars, habitat destruction, and illegal hunting.

It all began for Stany in Bujumbura, the capital of Burundi. This is where I, too, first came face-to-face with the awful reality of the chimpanzee pet trade. The then American ambassador to Burundi, Dan Phillips, and his wife, Lucie, begged me to visit Bujumbura, where they told me there were a number of chimpanzee infants being kept as pets, often in terrible conditions. Before we could persuade their owners to release them, it was necessary to find them accommodation. The first two, Poco and Socrates, were put in a big cage built especially for them in the backyard of the embassy residence. Next, we managed to raise money to build a halfway housea facility where we eventually kept twenty-two youngsters while searching for a location and the money for a proper sanctuary.

It was at this point that Stany came into the picture, when he joined JGI to help look after the growing chimpanzee family. Little did he know that this job would change the course of his life. It was clear from the start that he had a real gift for working with these creatures. He empathized with them and quickly came to understand the posture, gestures, and sounds that make up the chimpanzee language. He was able to communicate with them in a special way to the point that we called him a chimpanzee whisperer. Since that time, I have heard so many stories about his skill in resolving conflicts between individual chimpanzeesalso stories about how he could calm tense or nervous individuals and reassure the infants who arrived traumatized and often wounded, having been torn from their dead or dying mothers. He was frequently able to help fellow caregivers when they had difficulty coping with problem chimpanzees.

This relationship between human and chimpanzee is fascinating. It becomes even more extraordinary when set against the backdrop of a brutal civil war that tore Stanys country apart, claiming the lives of his parents and siblings and separating him for four long years from his wife and children. He had been with us for five years when fighting erupted in Burundi between the two main ethnic groups, the Hutu and the Tutsi. As is always the case, hundreds of innocent people suffered. Two of our staff were killed; others, including Stany, were beaten. That he survived was a miracle. It was clear we had to close the sanctuary, which meant that somehow, we had to relocate the chimpanzees to a safe place.

At this time Debby Cox arrived to take over the running of the halfway house. Little did she know when she agreed to join us that her first task would be to help JGI organize planes to transport twenty chimpanzees to Kenya. Debby of course chose their best human friend, Stany, to go with them. He could reassure them after the gunshots and a frightening plane journey, and he became solely responsible for their daily care.

The Kenya Wildlife Service had agreed to house them while a sanctuary was constructed for them. My friend Russell Clark, a manager with Lonrho, the large conglomerate specializing in mining, agriculture, and hotels, agreed to build the chimpanzees a sanctuary on land where they operated Sweetwaters Serena Camp just outside Nanyuki. It is part of the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, which is still home to many endangered species including elephant, rhino, lion, buffalo, and leopard, as well as chimpanzees.

When their new home was ready at Sweetwaters, Stany went with them to settle the chimpanzees in and help with the training of the new caregivers. He stayed for three months. By that time a new sanctuary manager had arrived, and Debby had been appointed to oversee the development of another sanctuary in Uganda. She needed Stany to help her, so he began a new life working with the orphaned chimpanzees of what would become the Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary.

I have been to that beautiful island on several occasions, renewing my friendships with the chimpanzees and the staff. Now there is accommodation for a few visitors in addition to the staff and spacious cages where the chimpanzees sleep at night in hammocks suspended high near the roof. On my last visit I got up early to watch Stany and his staff give the chimpanzees their breakfast of porridge and fruit before they were let out for their day of roaming the forest. Then there was time to sit with Stany to reminisce about the history of sanctuaries and some of the chimpanzees. I was able to share news of his old friends from Sweetwaters, Poco and Socrates and the rest.

Next page