Introduction

I am now in the land of corn, wine, oil, and sunshine. What more can man ask of heaven?

T HOMAS J EFFERSON

in Aix-en-Provence, March 27, 1787

ts an impossible business, trying to squeeze Provence into a single volume. Theres too much history, too much material. Thousands of years of human habitation; an encyclopedias worth of churches and chteaus, towns and villages; a small army of distinguished or notorious residents, including Petrarch, Nostradamus, Raymond de Turenne, and the Marquis de Sade; artists, poets, and writers galore: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Czanne, Frdric Mistral, Marcel Pagnol, Alphonse Daudet, and Jean Giono; legends and myths, mountains and vineyards, truffles and melons, saints and monsters. Where to start? What to include? What to leave out?

ts an impossible business, trying to squeeze Provence into a single volume. Theres too much history, too much material. Thousands of years of human habitation; an encyclopedias worth of churches and chteaus, towns and villages; a small army of distinguished or notorious residents, including Petrarch, Nostradamus, Raymond de Turenne, and the Marquis de Sade; artists, poets, and writers galore: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Czanne, Frdric Mistral, Marcel Pagnol, Alphonse Daudet, and Jean Giono; legends and myths, mountains and vineyards, truffles and melons, saints and monsters. Where to start? What to include? What to leave out?

Its a problem that many writers have faced, and their solution has often been to specialize. They have confined themselves to particular themesecclesiastical architecture, the influence of the Romans, the cultural significance of bouillabaisse, any one of a hundred facets of Provenceand they have produced comprehensive, often scholarly books. Admirable though these are, I havent attempted to add to that collection. Probably just as well, since Im no scholar.

Instead, I have compiled an autobiographical jigsaw of personal interests, personal discoveries, and personal foibles. That may sound like a cavalier way to approach a book, but I can at least say that I have observed certain rules and restrictions.

As much as possible, I have tried to avoid the more celebrated landmarks, buildings, and monuments. I have left to others the Pont du Gard, the Roman amphitheater at Arles, the Abbey of Snanque, the Palais des Papes in Avignon, and dozens more historic marvels that have already been so frequently admired and so well described. For the same reason, I have neglected great tracts of glorious countryside, like the Camargue, and one of the most beautiful stretches of the Provenal coastline, the Calanques east of Marseille.

My choice of subjects has been guided by a set of simple questions. Does the subject interest me? Does it amuse me? Is there an aspect of it that is not very well known? Its the technique of the magpie, hopping from one promising distraction to another, and it has the great advantage of being virtually all-inclusive. Anyone or anything can qualify, as long as it has piqued my curiosity. That, at any rate, is my justification for assembling a collection that includes such unrelated topics as a recipe for tapenade and a morning spent with a public executioner.

In the course of my research, I have often been reminded of the Provenal love of anecdote, conversational embroidery, and the barely credible story. I make no excuses for recording much of what Ive been told, however unlikely it may sound. We are, after all, living through a period in which the truth is routinely distorted, usually for political advantage. If I have sometimes overstepped the limits of verifiable accuracy, at least I have done so in a good cause, which is to make the reader smile.

In the same spirit, I have not questioned too closely some of the specialist information passed on to me by experts, and Provence is full of experts. Almost without exception, they are generous with their time, their advice, and their opinions. The problem comes when you ask two of these experts the same question. When is the correct time to pick olives? How can I keep scorpions out of the house? Is the Provenal climate changing for the warmer? Is pastis the cure for all ills? Invariably, you will receive totally conflicting answers, each delivered with enormous conviction. I admit that I always choose to believe the most improbable one.

Among these experts, one in particular deserves to be mentioned here, even though he also appears several times in the pages that follow. He is the emeritus professor Monsieur Farigoule. Now retired from the mainstream of academic life, he has established a charitable course for the education of backward foreigners, and I am his favorite pupil. In fact, I think I may be his only pupil. Lessons are held in the local caf, and the curriculum is remarkably wide-ranging, since Monsieur Farigoule seems to be an expert on everything. Among other things, I have tried him on hornets nests, Napolons love life, the use of donkey dung as fertilizer, the poetry of Mistral, the essential character differences between the French and the Anglo-Saxons, and the Avignon Papacy. He has never been short of an answer, is usually contentious, and is always extremely opinionated. It is to this unconventional muse that I owe a considerable debt, which I now acknowledge with great pleasure.

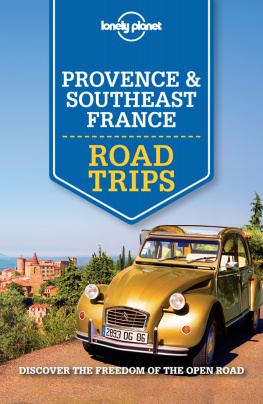

Some Unreliable Geography

It seems to me that almost everyone, from the first Roman mapmaker onward, has had very definite ideas of exactly where Provence is. But unfortunately for the seeker after geographical truth and precision, these ideas have varied, sometimes by hundreds of kilometers. I was told, for instance, that Provence commence Valence, way up north in the Rhne-Alpes dpartement. Recently, I made the mistake of passing this information on to my personal sage Monsieur Farigoule, who told me that I was talking nonsense. One might stretch a point, he said, and include Nyons in Provence, as a reward for its splendid olives, but not one centimeter further north. He was equally adamant about the eastern boundary (Nmes) and the western limit (Sisteron).

The fact is that, over the centuries, boundaries have expanded and contracted; a bulge here, a dent there, sprawling or shrinking. Names have changed, too, or have disappeared from popular use. Not long ago, the lowly Basses-Alpes were given a leg up in the world and promoted to the Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. And who nowadays could tell you with any conviction where the Comtat Venaissin begins and ends? It is not an exaggeration to say that the whole area, for many years, was an affront to the French sense of neatness, order, and logic.

Clearly, this haphazard, almost medieval state of affairs couldnt be allowed to continue in the modern world. Something had to be done. And so eventually, throwing up their hands in frustration, the officials in charge of such matters decided to consolidate several dpartements of southeastern France into one new, all-embracing region. Naturally, this needed a name, and who better to provide one than that shadowy but influential figure, the minister in charge of acronyms? (We can thank him for such triumphs as CICAS, CREFAK, CEPABA, CRICAand these come from just a brief glance at the Vaucluse telephone directory. There are literally thousands of others.)

The minister was called in. He rummaged through the alphabet and deliberated. And having deliberated, he brought forth. PACA was born: Provence-Alpes-Cte dAzur, stretching from Arles in the west to the Italian frontier in the easta single, tidy, administratively correct geographical unit. What a relief. At last we all knew where we were.

ts an impossible business, trying to squeeze Provence into a single volume. Theres too much history, too much material. Thousands of years of human habitation; an encyclopedias worth of churches and chteaus, towns and villages; a small army of distinguished or notorious residents, including Petrarch, Nostradamus, Raymond de Turenne, and the Marquis de Sade; artists, poets, and writers galore: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Czanne, Frdric Mistral, Marcel Pagnol, Alphonse Daudet, and Jean Giono; legends and myths, mountains and vineyards, truffles and melons, saints and monsters. Where to start? What to include? What to leave out?

ts an impossible business, trying to squeeze Provence into a single volume. Theres too much history, too much material. Thousands of years of human habitation; an encyclopedias worth of churches and chteaus, towns and villages; a small army of distinguished or notorious residents, including Petrarch, Nostradamus, Raymond de Turenne, and the Marquis de Sade; artists, poets, and writers galore: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Czanne, Frdric Mistral, Marcel Pagnol, Alphonse Daudet, and Jean Giono; legends and myths, mountains and vineyards, truffles and melons, saints and monsters. Where to start? What to include? What to leave out?