Table of Contents

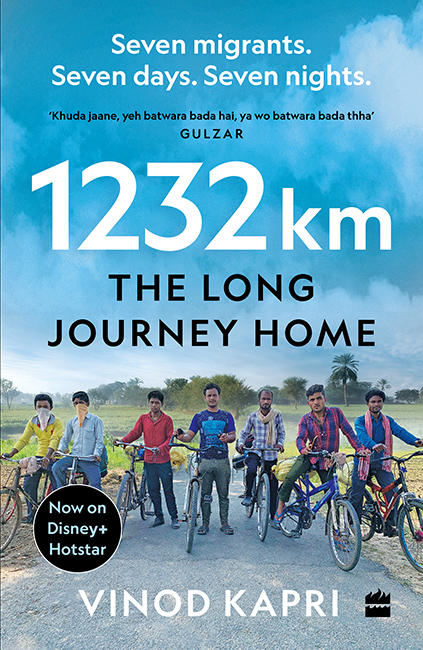

Dedicated to my heroesRitesh, Ram Babu, Ashish, Krishna, Mukesh, Sandeep and Sonu.

Contents

I NDIAS COVID-19 LOCKDOWN was announced on television around 8 p.m. on 24 March 2020 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to break its chain of infection, and took effect barely four hours later. It was subsequently extended in three phases up to 31 May, and is widely regarded as one of the worlds most draconian responses to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Ordering a total lockdown of twenty-one days on a vast country with a population of 1.38 billion meant that nobody outside the exempted categories could step out of their homes. The prime minister explained that the idea was to protect the country and each of its citizens.

But were the governments and the system able to deliver on this promise? And was there any real chance that they would be able togiven the deadly combination of mass deprivation, policy insensitivity and social indifference that had accumulated over decades of unequal, distorted development?

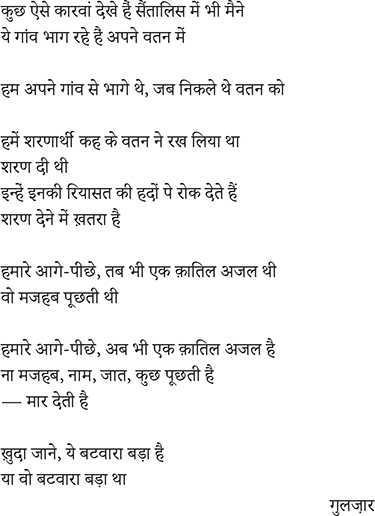

What unfolded on the ground over the next ten weeks is best captured in these lines of the poet:

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

(T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men)

The Pandemic-Lockdown, its socio-economic impact, and the difference it made to the spread of Covid-19, have spawned a large literature of uneven quality, authenticity, relevance and interest. This literature comprises newspaper and television reports and analyses; field surveys by non-government organizations (NGOs) and other organizations (domestic as well as international); scholarly studies; citizen journalism on social media; and, of course, material put out by the central and state governments. It includes information and data relating to Covid-19; the medical, administrative, and other measures taken to halt its spread; the relief packages for the key economic sectors and for vulnerable sections of the population.

While it seems true that India, along with a number of other developing countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America, has so far suffered significantly less morbidity and mortality directly traceable to Covid-19 than have most developed countries, there is nevertheless a very dark side to this story. The darkness of mass distress, destitution, brutality and death that calls for democratic accountability from governments and other political actors, as well as lessons to be learnt on all sides.

The failure of the central government and most state governments to come to the aid of tens of millions of working people stranded far from home, with no money or food, confronting a lethal combination of crises: health, hunger, sanitation, and trauma, both physical and psychological, and desperately wanting to be extricated from the continued trauma and helplessness and be able to go home; the most basic of human needs, took a devastating social and human toll.

The phenomenon of the Covid-19 migrant on the move, reflects jurist and scholar on constitutional law Upendra Baxi, was all about the senseless social suffering that thingified human beings and converted their suffering into commodities in markets of governance, justice, development, and human rights. methods deployed, proved to be no match for the desperation, the tenacity and the spirit of those who defied the Pandemic-Lockdown to walk or bicycle the long distance home.

Baxi calls our attention to an important truth that often eludes the understanding of those in authority. These migrant workersgambling with exhaustion, hunger, disease, fatigue and even death, in a new form of spontaneous mass civil disobedience that policymakers and political actors had completely failed to anticipatedemonstrated that they were acting as individual moral actors, rather than as an inert mass of moral patients.

As might be expected, given Indias historical tradition of socially purposeful, public-service journalism, there has been some sensitive and evocative reporting of this unprecedented crisis and the conspicuous failure of the central and state governments to provide an elementary safety net. However, what is undeniable is that Indias established or mainstream news media failed on the whole to comprehend and respond to the gravity and enormity of the crisis brought on by the unplanned and callously implemented Pandemic-Lockdown.

According to a World Bank study, the lockdown in India has impacted the livelihoods of a large proportion of the countrys nearly 40 million internal migrants. For its part, citizen journalism on social media platforms and messaging apps served up a mixture of useful, interesting and even life-saving information in real time, along with a great deal of toxic disinformation and communal and class hatred.

Unsurprisingly, the central and several state governments came out with wagonloads of propaganda based on demonstrably untrue claims on how well they were able to handle the socio-economic crisis brought on by the Pandemic-Lockdown.

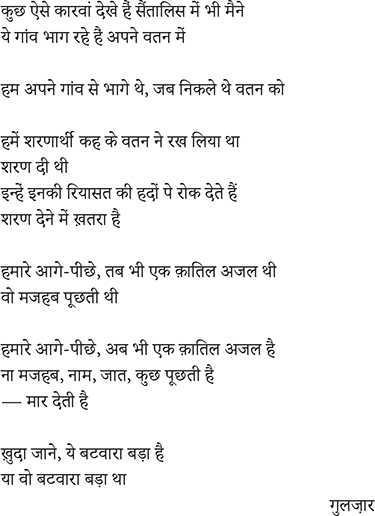

Against this background, 1232 km: The Long Journey Home by Vinod Kapri, award-winning filmmaker and experienced journalist, stands out as an extraordinary story. It is a real-life tale of seven young migrant workersRitesh, Ram Babu, Sonu, Mukesh, Krishna, Sandeep and Ashishbicycling their way back home in the face of all manner of obstacles, deprivations and threats to life and health. The rough ride of 1232 km, as calculated by Ritesh on the Google Maps app of his mobile phone, begins in a labour colony in Uttar Pradeshs Ghaziabad city, which is part of the National Capital Region of Delhi, and ends at their villages in the Saharsa and Samastipur districts of Bihar. What happens during this journey of seven days and seven nights is deeply distressing, affecting and inspiring in turn.

The author and his colleague, Manav Yadav, follow the seven young men in a WagonR, armed with a Sony FS-5 camera and iPhones, recording the events as they unfold from their car. They have set clear rules for themselvesnever be a hindrance on this journey; do not stage anything for the camera; shoot whatever the seven do from a respectable distance; and do not ask too much of them unless the road is clear, and they are ready to talk. Because the documentarists were completely unprepared for the decision of the migrant workers to make the long and perilous journey back home on bicycles, they miss the events of the first day and night. The particularly harrowing experience that the seven young men endure that first day is later narrated to them.

The storyteller is part of the story, his primary task is to bear witness. How the author and his colleague go about crafting, moderating and, where necessary, gearing up their role as documentarists and journalistsbut also, as the situation develops, acting as citizens and independent moral actorsis instructive. Can the reporter or storyteller maintain a studied professional distance when danger to human life and health lurks in the air?

Striking some kind of balance, between influencing, even mentoring, but not acting as a deus ex machina contriving a solution, proves to be a challenge. Several times during the journey, Kapri wrestles with the question of whether he is trying to turn their tragedy into an opportunity. But reasoning that if the toughest journey of their lives is not documented, the country and the world will not learn about their struggle, their pain and the threats they face, he sets about doing what he has to do.