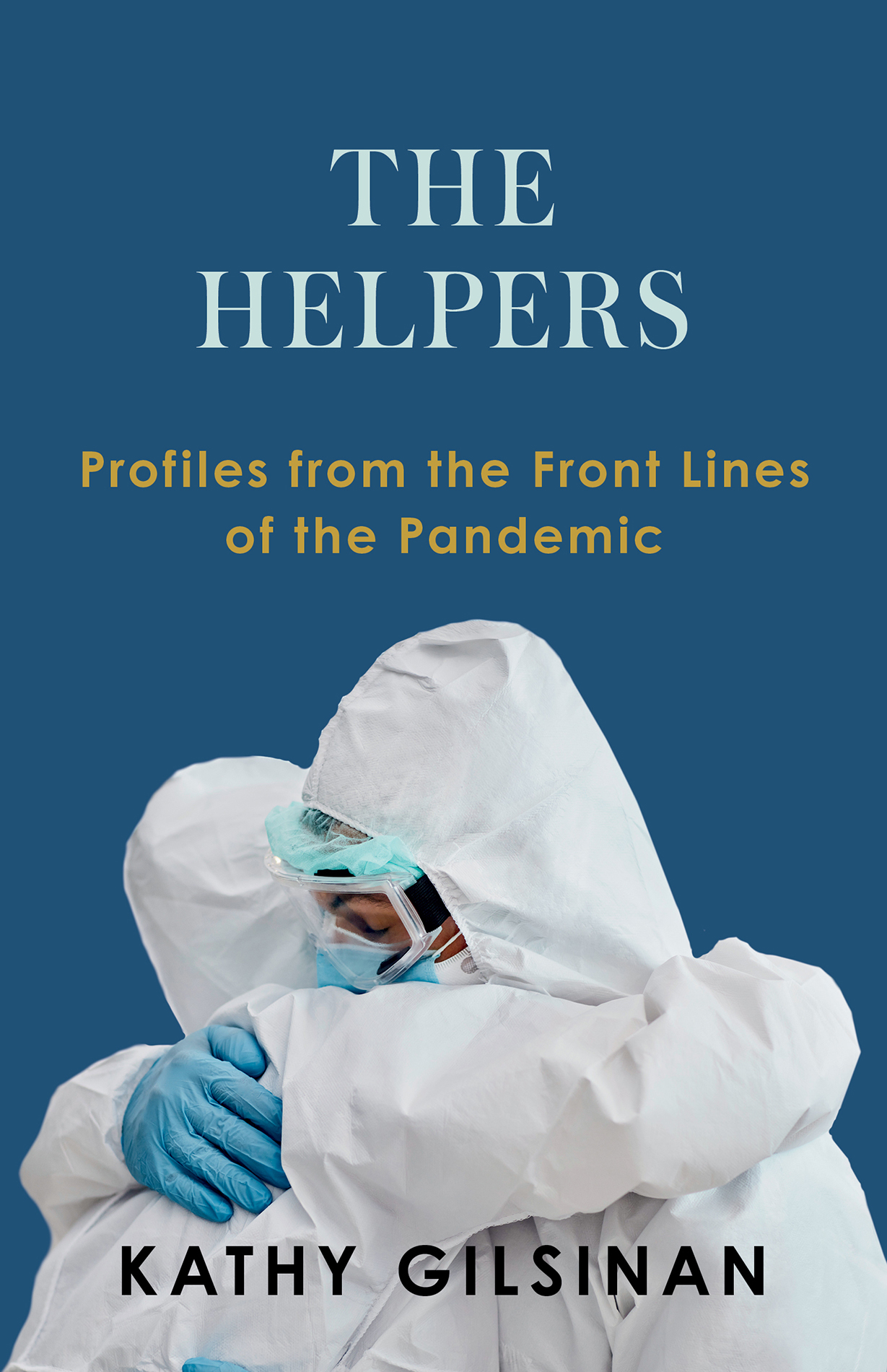

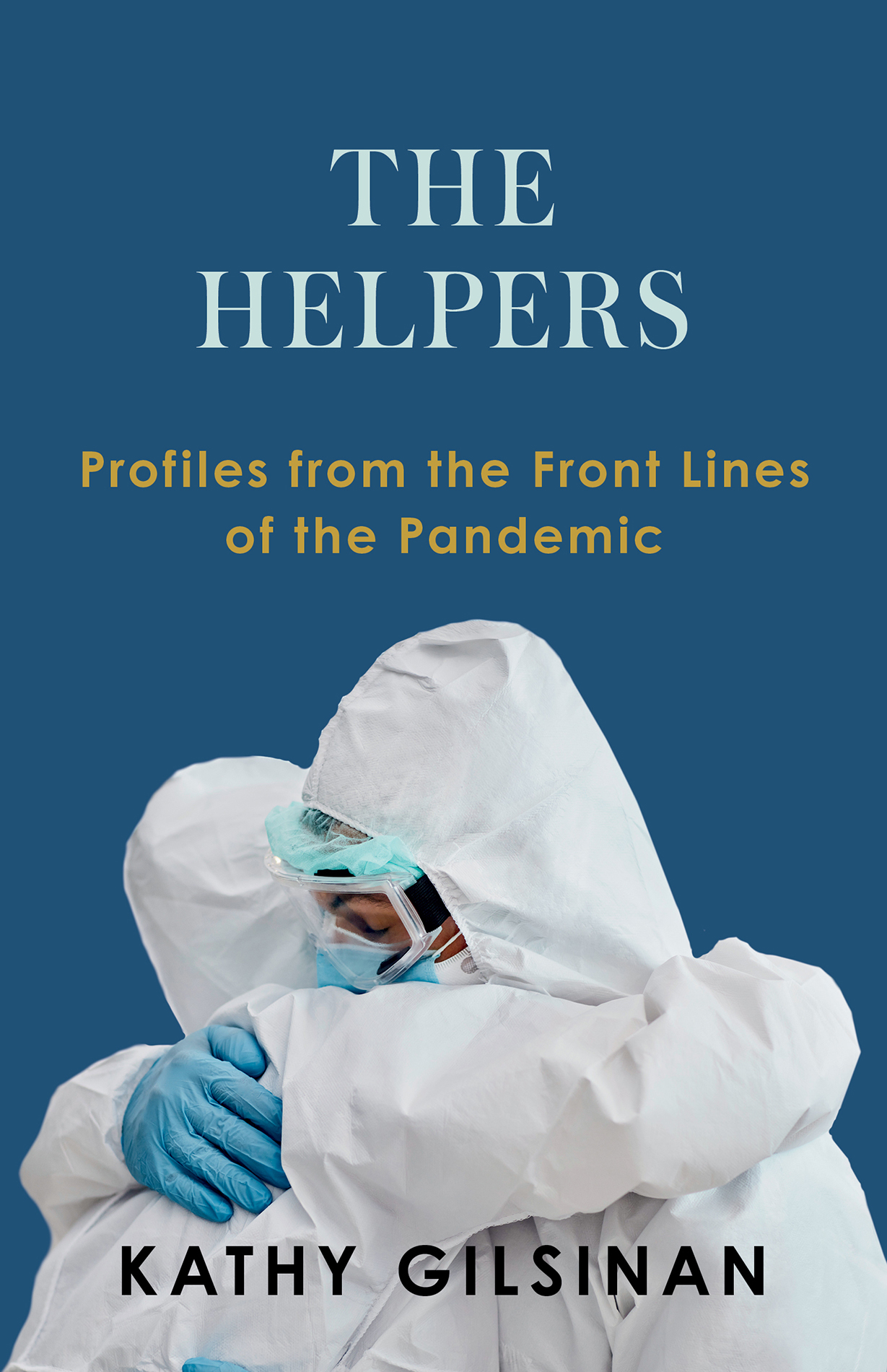

THE

HELPERS

Profiles from the Front Lines

of the Pandemic

KATHY GILSINAN

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

All the darkness in the world cannot extinguish the light of a single candle.

SAINT FRANCIS OF ASSISI

... To state plainly what we learn in times of pestilence: that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.

ALBERT CAMUS, THE PLAGUE

We can only do what we can: but that we must do, against difficulties.

ISAIAH BERLIN, THE PURSUIT OF THE IDEAL

For Mom and Dad Selfless helpers, dear friends, and north star(s) to your girl Thank you.

L IFE, FOR ME, came back like an old friend. Id lost touch with her for too long, but we resumed our old rhythms so easily I could almost feel like no time had passed. What Id missed and appreciated about herhugs and handshakes and casual chats with strangers, wide smiles unmaskedI quickly started taking for granted. And I soon rediscovered her forgotten flaws, the burdens of proximity to other people, the annoyances of social obligations Id recently sworn I would cherish if I could just have them again.

The recovery happened to us one by one, or not at all. We lurched into a post-vaccine summer in 2021, by which time 150 million were vaccinated and 600,000 had died in the United States, a toll that would surpass 700,000 by years end. We watched the virus ravage countries that lacked our vaccines, even as we, the American survivors, went on vacations or stayed hunkered down; we made up for lost time with friends or discovered we didnt want to; we went back to work or tried to avoid it or didnt have jobs to go back to or had never stopped going at all. Newspaper advice columns shifted attention, from coping with isolation to dealing with company. The mass layoffs of 2020 became the worker shortage of 2021; fears of another Great Depression became worries about inflation.

And still the virus wasnt fully vanquished, and still, just as in Camuss The Plague, the end of the story here cant be one of final victory. His plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good; it lurks for years in furniture and linen-chests... in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, and bookshelves, biding its time to rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city. Our coronavirus continues to spread, in America and around the world; it dwells in peoples lungs and in the air around them, and in monkeys, cats, deer, and mink; it morphs into new variants and finds new victims; it courses through undervaccinated parts of the United States where people either refuse or cant get shots.

What meets it still is the stubborn spirit that drove the people in this book to help others. In place of victory is ongoing struggle, never finished, never enough. You can never save enough people, you can never make or distribute a vaccine fast enough or convince enough people to take it, you can never feed all of the hungry. But there are people who look those odds in the eye and try anyway.

They do this even when their elected leadership and public institutions fail them; they chase down the resources to save lives while politicians bicker and buck-pass and evade responsibility, and fellow citizens turn on each other. As much as this book is a story about individual heroism, it is also by implication an indictment of the institutions that left them unsupported or unprotected, and whose failures made so much of their courage necessary in the first place.

At the same time, The Helpers isnt a partisan morality tale. The virus further polarized a deeply politically divided country, but it also didnt care which side of the divide its victims fell on. Nor did the helpers described here: They include Trump supporters and socialists, and no one is worried about anyone elses party affiliation in the ICU or at the food pantry. Even at our most divided, our country is so much bigger and better than our politics.

Around the new year in 2021, when wed all put our despised 2020 behind us but not yet our pandemic, I asked the helpers in this book what theyd learned in their separate fights with the virus and its effects. Everyone was ambivalent or modest in the lessons they drew. Hamilton Bennett reflected on how much the pandemic had taken from everyone, and on resilience in the face of loss. Chris Kiple, ever the CEO, had found new appreciation for a vital mission and teamwork; Huy Le wanted to find ways to live a more meaningful life. Michelle Gonzalez was happy to be alive and angry at institutions and leaders she thought had refused to care for the vulnerable or fix their obvious problems; Nikkia Rhodes stayed committed to gradual change in her community and to raising up the next generation of Black leaders. I never got to speak to Paul Cary, but I often think of what one of his colleagues told me about his attitude: That even facing the certainty of losing, you still show up to play. The helpers who are still with us told me about their hope for an eventually better future and the way love is heightened by the prospect of loss, the way gratitude intensifies when deprivation is all around.

I admit I wanted something bigger and more sense-making about human nature, and Americans nature in particular. Surely the ideas of gratitude and striving and teamwork couldnt be it. But as I kept thinking about it, I realized that really was it. We suffered on a grand scale and coped on a small one. Most of us tried and many of us failed. Some risked everything to save other people; we, the helped, owe our gratitude and in some cases our very lives to them.

In The Plague, Camus winds up modestly but stubbornly hopeful about human beings, a conclusion that strikes me as appropriate to the scale of human capabilities. His protagonist Dr. Rieux watches the fireworks of a city finally liberated from pestilence and reflects that, absent victory, his could be only the record of what had to be done, and what assuredly would have to be done again in the never-ending fight against terror and its relentless onslaughts, despite their personal afflictions, by all who, while unable to be saints but refusing to bow down to pestilences, strive their utmost to be healers.

March 16March 19, 2020

H UY LE WRENCHED HIMSELF out of bed at an awful predawn hour because thats what a good little brother does. His sister Uyns flight to Chicago for a teaching seminar was departing around 5:00 a.m. on March 16, and naturally it was his job to ferry her through the dark quiet to the San Jose airport from their parents house just north of the city. Huy took the responsibility; everyone else could sleep.

Uyn planned to leave her two-year-old son, Kai, with her parents while she traveled, then retrieve him on her way back home to her husband and her job as a family medicine doctor in Nevada. Creeping out of the house that spring morning, Huy found his mom dozing on the couch and asked her softly to go check on the little one and sleep in his room in case he woke up needing something. His mom muttered a foggy assent. Okay, go.

Huy had his own place, a condo in San Francisco, financed by long employment with Silicon Valley tech giants10 years at Apple and another 7 months at Facebook. But he still made a point to spend a night or two a week at his parents place in Milpitas, the South Bay town where he grew up. This was only partly because doing so shaved off a lot of the commute time to the Facebook offices in Menlo Park. Mostly, he was close to his family, just as serious about being a son as being a little brother.

Next page