SHRABANI BASU is a journalist and author. Her books include Victoria & Abdul: The Extraordinary True Story of the Queens Closest Confidant , now a major motion picture, Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan and For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front, 191418 . In 2010, she set up the Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust and campaigned for a memorial for the Second World War heroine, which was unveiled by Princess Anne in London in November 2012. In August 2020 she was invited by English Heritage to unveil the Blue Plaque for Noor Inayat Khan in London.

shrabanibasu.co.uk

@shrabanibasu_

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Curry: The Story of the Nations Favourite Dish

Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan

Victoria & Abdul: The Extraordinary True Story of

the Queens Closest Confidant

For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the

Western Front, 191418

BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING and the Diana logo are

trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2021

This edition published 2022

Copyright Shrabani Basu, 2021

Shrabani Basu has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988,

to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the on pp. 2957 constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system,

without prior permission in writing from the publishers

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: HB: 978-1-5266-1528-2; TPB: 978-1-5266-1530-5; eBook: 978-1-5266-1529-9;

PB: 978-1-5266-1531-2

Typeset by Newgen KnowledgeWorks Pvt. Ltd., Chennai, India

To find out more about our authors and books visit

www.bloomsbury.com and sign up for our newsletters

For my late father,

Chitta Ranjan Basu

Contents

But look at these lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.

Sherlock Holmes in The Adventure of

the Copper Beeches (1892)

The police should get rid of the notion that anyone whose name they were unable to spell or pronounce is a foreigner, or that foreigners are most likely to commit such ferocious crimes.

George Edalji, September 1912,

in the Daily Mail

I am an English woman, and I feel that there is among many people a prejudice against those who are not English, and I cannot help feeling that it is owing to that prejudice that my son has been falsely accused.

Charlotte Edalji to Sir George Lewis,

25 January 1904

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle author, creator of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries

Jean Leckie Sir Arthurs second wife

The Edalji household

Shapurji Edalji Vicar of Great Wyrley

Charlotte Edalji the vicars wife

George Edalji eldest son of the vicar

Horace Edalji second son of the vicar

Maud Edalji daughter of the vicar

Elizabeth Foster maid

Dora Earp maid

The Staffordshire police

Captain Hon. G. A. Anson chief constable

Sergeant Upton

Inspector Campbell

Sergeant Robinson

Village locals

Royden Sharp

Fred Brookes

Fred Wynne

Wilfred Greatorex

Harry Green

Frank Arrowsmith

R. Beaumont

Campaigners

Justice Roger Dawson Yelverton, retired Chief Justice of the Bahamas

Sir George Lewis, leading criminal lawyer

Henry Labouchre, MP

In keeping with the period of the book, I have used the old spellings for city names (Bombay instead of Mumbai, Cawnpore instead of Kanpur etc.).

Parsee can also be spelt as Parsi. I have chosen to use the old spelling.

Hindoo was used generically by the British to describe all Indians, and not necessarily those persons who practised the Hindu religion.

Warning: animals are hurt in this story

The train pulling out of Birmingham New Street at 12.12 p.m. was not very crowded: a middle-aged couple, a young Japanese girl anxious to know if it would stop at Walsall, a group of young boys in their teens. The train was going to Rugeley, a small town in Staffordshire, an hour away. To the other passengers, busy on their phones, there was nothing remarkable about the train which would go past eight small stations in the Midlands. I was trying to trace the journey that would have been made by George Edalji, first as a schoolboy, then as an adult, on the same branch line over a hundred years ago.

George lived with his Indian father and English mother in the small village of Great Wyrley. His father, Shapurji Edalji, was the Vicar of Great Wyrley. Georges mother, Charlotte Stoneham, had taken the daring step of marrying an Indian man at a time when interracial marriages were frowned upon. Shapurji, a Parsee from India who had converted to Christianity, had become the first South Asian to be appointed a vicar in Britain in 1876. George was born the same year. I was heading to St Marks Church and the Old Vicarage, once the home of the Edalji family.

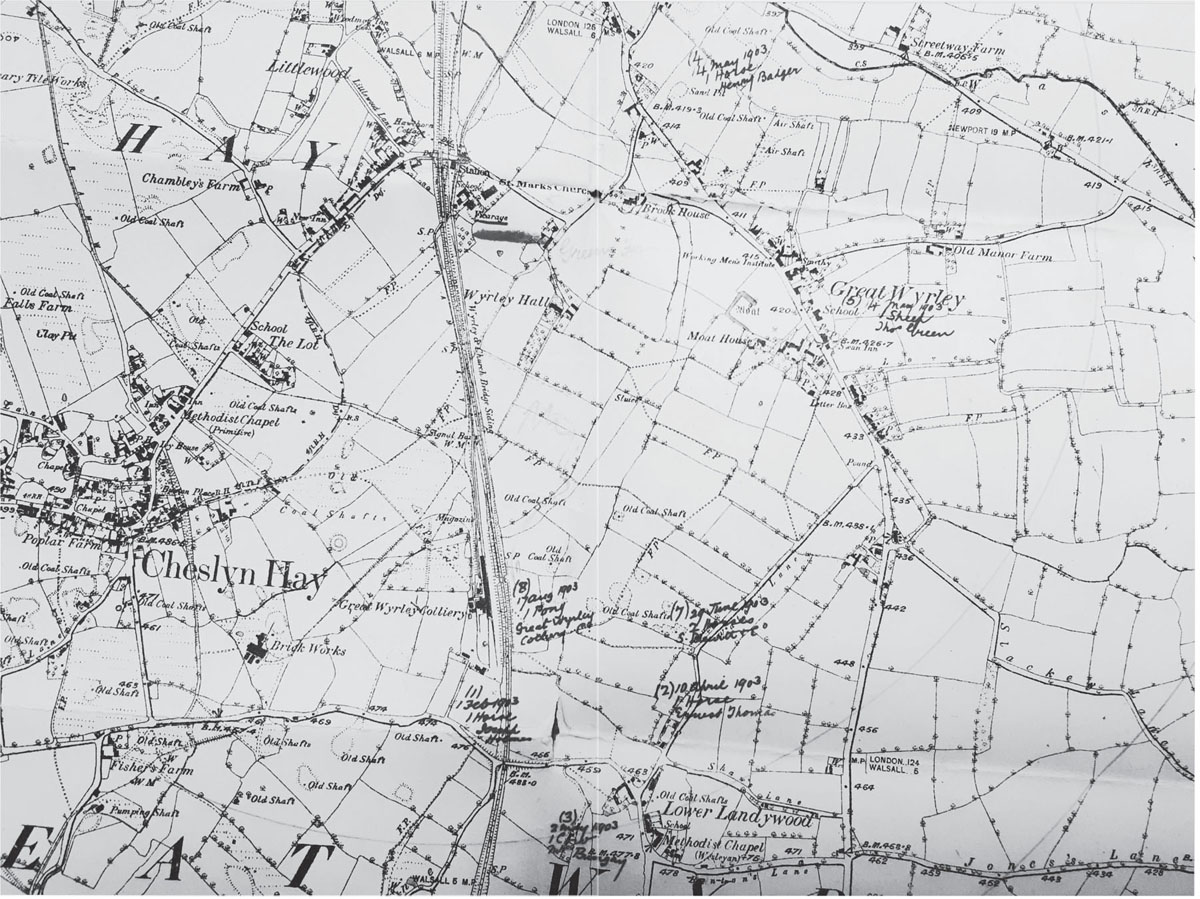

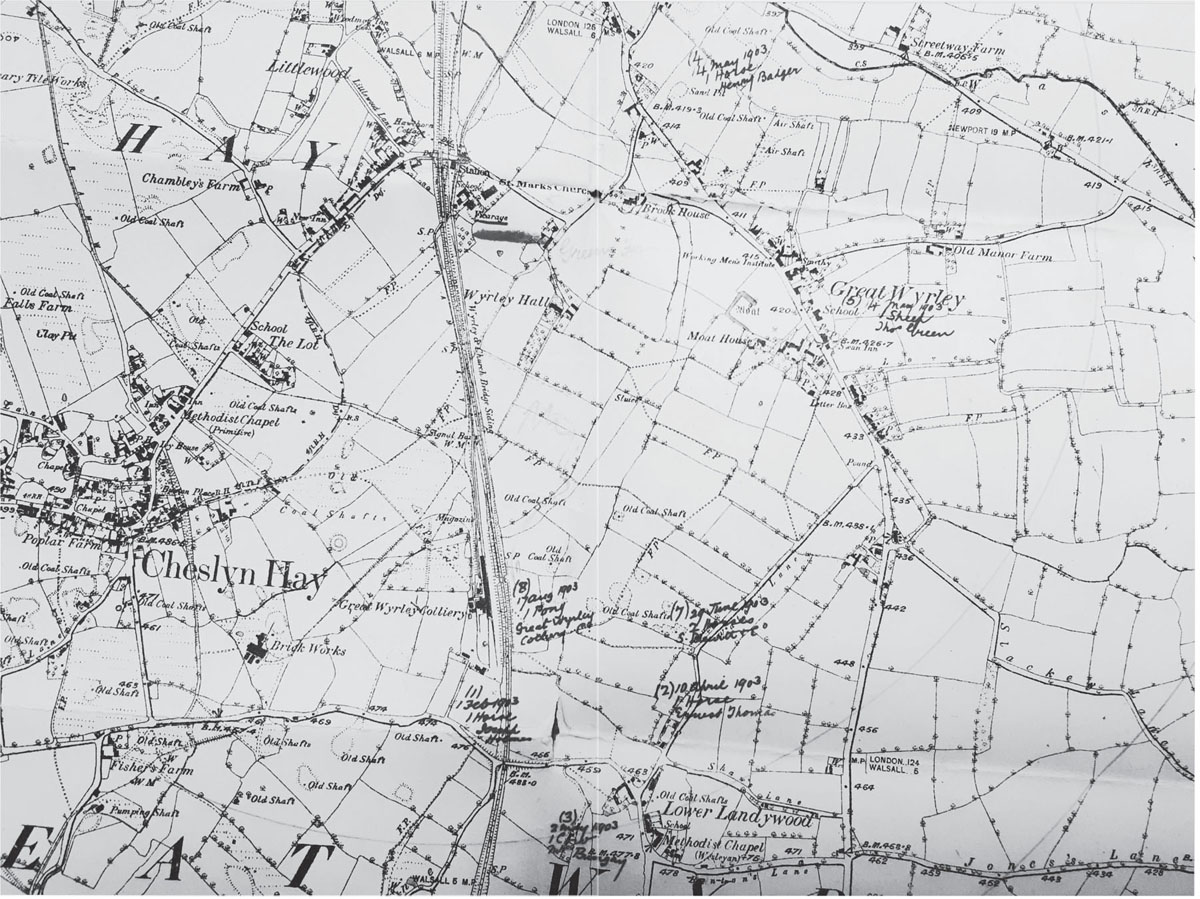

The rain slashed against my window as the train chugged through the semi-industrial town of Walsall, passing behind the backs of houses, car-repair workshops, garages, tyre shops and small industrial units. Soon we were out in open fields with sheep and horses standing patiently in the rain, as if watching the train go by. Once there were mines and collieries on this land. Shafts rumbled through the night bringing up coal from the depths. Boys as young as twelve would go down the pits following in the footsteps of their fathers and grandfathers. Horses and pit ponies were the mainstay of the area, pulling the cartloads of coal to the canals and railway wagons for transport to the industrial centres in the north. Sheep dotted the countryside, then, as they did now.

I was passing through a region that had provided the most sensational crime and subsequent trial in Edwardian Britain. The branch line running between Walsall, Bloxwich, Landywood, Cannock, Hednesford and Rugeley was the link to a series of brutal animal mutilations committed over a century ago. Every village had a connection with the story. Beneath the normality of my present commute, I felt I was entering what would have been the heart of darkness.

Looking out of the train window in June 1903, George would have seen two horses lying savagely attacked in the fields, their entrails hanging out. It would be on the platform at Wyrley and Cheslyn Hay station on that fateful day in August 1903 that he would be told that the inspector wanted to see him.

The arrest and trial of George Edalji for the alleged mutilation of a horse and the threat to kill a policeman attracted huge media attention. The dark-skinned prisoner, son of a Hindoo vicar provided fodder for scribes to focus on the mysterious Orient. George was sentenced to seven years penal servitude. He was released three years later on parole.

Next page