Contents

Guide

First published in 2021 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Phillip Hills 2021

The moral right of Phillip Hills to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 668 7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

For Maggie

Contents

List of Illustrations

DIAGRAMS

Prologue

In February 1990, when Voyager 1 finally left the heliosphere and was nearly four billion miles from home, it sent back photos of the Earth as seen from the edge of the Solar System: it appeared as a pale blue dot in an immensity of darkness. Never before had humankind been given such a perspective on the planet which we call home. In the far future we may look back on this moment with something of the emotion that Europeans felt in the century after they discovered the Americas. For we can be fairly confident that, if we survive, this will be seen as the beginning of our species liberation from our planetary origins.

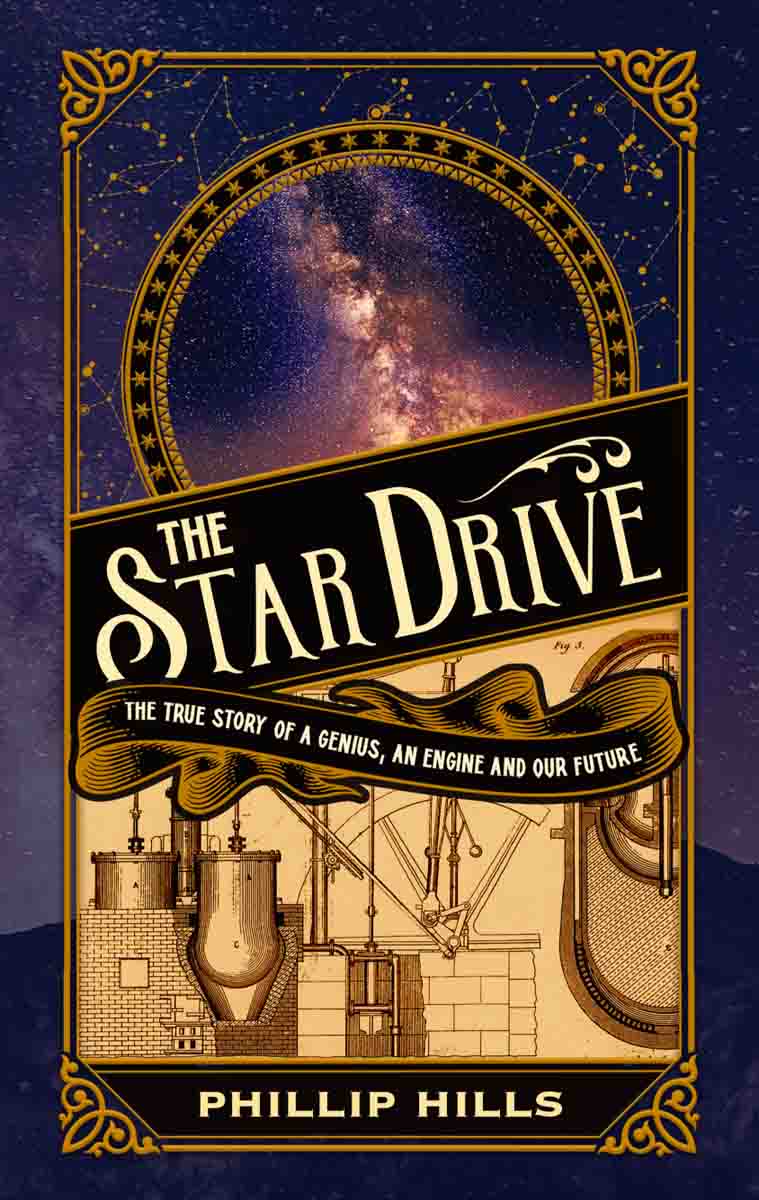

The exploration of the Solar System has been made possible by the greatest concentration of technological innovation our planet has seen, and the leader of that effort for the last thirty years or so has been NASA, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration of the United States. Most people who have any interest in space exploration are aware of this; what few people know is that at the core of the project, and essential to its future success, is an engine which will power all the functions of the spacecraft. It does this by converting the heat of a nuclear fission reactor directly into electricity. The engine was invented more than two centuries ago by a Scottish minister of the Kirk called Robert Stirling and the Stirling engines which spacecraft will now carry are not so different from the drawings which young Robert made when he applied to patent it in 1816.

In May of 2018, NASA called a press conference to announce the successful test-run of their KRUSTY machine. They explained that KRUSTY was an acronym for an electricity generator to be used for manned bases on the Moon and the nearer planets, and for distant space missions all of which require a compact, reliable and small source of electrical power. The output of solar photovoltaic cells falls off beyond Jupiter and radioisotope generators dont produce enough power to run a dishwasher. (All starships will need a dishwasher.) KRUSTY will provide support for life on satellites and planets and, eventually, propulsion beyond the Solar System.

KRUSTY stands for Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling Technology. The first part of the acronym is largely self-explanatory: a kilopower reactor is a very small nuclear reactor which produces heat sufficient to generate a few kilowatts of electricity. This doesnt sound much, given the scale of the ambition, and a million times less than you would expect from a normal nuclear power station, but its a lot more than astronauts have been used to until now. But what about using Stirling technology? Technology we know about, but what has it got to do with the name of a town in Central Scotland? The answer, of course, is that the thing uses the engine invented by Robert Stirling, and named after him, to convert the heat of the reactor into electricity.

So an engine on which humanitys greatest enterprise depends was invented by a Scotsman more than two hundred years ago: how astonishing. You could be forgiven for wondering why you have never heard of him or his engine. A few people have, of course, and the engine is well-known to enthusiasts around the world. But if you stop people on the street in Scotland and ask them, you will find they know nothing about it. (I can tell you this is the case: I have tried it.) The book which follows is about that engine and about the people many of them very remarkable who have brought it to the point at which it can be installed on a spaceship and expected to run nonstop, without repairs or maintenance of any sort, for tens, perhaps hundreds, of years.

Since the Stirling engine is the only known way of producing an appreciable quantity of long-term electrical power on a spacecraft, and all feasible ways of propelling a starship require electricity, it is reasonable to believe that when a spacecraft from this planet finally makes it to one of the nearer stars, its systems and its propulsion will be thanks to the power from the Stirling engine. Truly, a Star Drive.

INTRODUCTION

The Portobello Road

One fine Friday morning, many years ago, Dick and I walked over to the Portobello Road. It is an undistinguished thoroughfare in north London undistinguished save on Friday mornings, when there is a street market and it is transformed into something magical. In the market are sold fruit and fish, falafels and hot dogs, old clothes and miscellaneous junk. There is a distinction in the matter of junk, for at the south end it aspires to the status of antiques, while at the north there is no such pretension. Needless to say, the north end is the more interesting.

Having walked the length of the road that Friday, Dick and I stopped by a stall whose merchandise, unusually for the south end, appeared to be of a technical and mechanical nature. On the ground for the stall was heavily laden lay a curious little machine.

Whats that? I asked the stallholder.

Some kinda model steam engine, he replied.

May I lift it onto the stall? I asked.

Sure, he said.

I picked up the device and sat it on a space which the chap had obligingly cleared. It was surprisingly heavy, about 2 feet long and evidently made of cast iron. There were two parallel cylinders joined by a pipe and one of the cylinders had a frill of what appeared to be cooling fins. Rods emerging from the cylinders connected to a shaft, which carried a small flywheel. I gently turned the flywheel and one of the rods went in and the other out.

I dont think its a steam engine, I said.

Dick was looking closely at it. I dont recognise it at all, he ventured. What do you think it is?

I hesitated. Its never a good idea to be too forthcoming if a negotiation is in view and the guy you are to negotiate with is listening closely. Another customer came by and the stallholder transferred his attention.

I think maybe its a Stirling engine, I said.

Whats that? Dick asked.

I frowned. Im not sure. Ive never seen one in the flesh. Only read about them. They were common a century or more ago. I think if that bit I pointed to the end of one of the cylinders is heated, the thing will run.