First Mariner Books edition 2009

Copyright 2008 by Jonathan Lopez

Originally published as The Man Who Made Vermeers

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Portions of this work were published in slightly different form, chapter two as Gross False Pretences in Apollo, December 2007; chapter three as The Early Vermeers of Han van Meegeren in Apollo, July/August 2008; and chapters four and seven in Dutch as De meestervervalser en de fascistische droom in De Groene Amsterdammer, September 29, 2006.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Lopez, Jonathan.

The man who made Vermeers: unvarnishing the legend of master forger Han van Meegeren/Jonathan Lopez.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Meegeren, Han van, 18891947. 2. Art forgersNetherlandsBiography. 3. PaintersNetherlandsBiography. 4. Vermeer, Johannes, 16321675Forgeries. I. Title.

ND1662.M43L67 2008

759.9492dc22 [B] 2008005727

ISBN 978-0-15-101341-8

ISBN 978-0-547-24784-7 (pbk.)

Cover 2020 Columbia TriStar Motion Picture Group, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

e ISBN 978-0-547-35062-2

v3.1020

For Laura

Introduction

A Liars Biography

A T THE END OF W ORLD W AR II, shortly after the liberation of Amsterdam, the Dutch government threw wealthy artist Han van Meegeren into jail as a Nazi collaborator, charging that he had sold a priceless Vermeer to Hermann Goering during the German occupation. In a spectacular turn of events, Van Meegeren soon broke down and confessed that he himself had painted Goerings Vermeer. The great masterpiece was a phony.

While he was at it, Van Meegeren also admitted to forging several other pictures, including Vermeers famed Supper at Emmaus, the pride of Rotterdams Boijmans Museum, a painting once hailed by the prominent art historian Abraham Bredius not merely as a masterpiece, but indeed the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft. When the news got out, it made headlines around the world, and the forger became an instant folk hero. In widely reported interviews at the time, Van Meegeren claimed to be a misunderstood genius who had turned to forgery only late in life, seeking revenge on the critics who had scorned him early in his artistic career.

An ancient grievance redeemed; a wrong put right. It was a wildly appealing tale back in 1945, and indeed it remains quite seductive today. In the Netherlands, where Van Meegeren is still a household name, the story of the wily Dutchman who swindled Hermann Goering continues to raise a smile.

But the forger had one more trick up his sleeve: his version of events turns out to have been extravagantly untrue.

L IKE MANY OTHERS, I was originally drawn to Han van Meegeren by the sheer cleverness of what the man had accomplished. Yet, in pondering his story over the years, I found that much of it simply didnt add up. How could anyones first attempt at art forgery have yielded so large, complex, and distinctive a composition as The Supper at Emmaus? As I delved deeper into the subject, I gradually came to understand that Van Meegeren had not been a meek and downtrodden artist on a quest for personal vindication, but rather a truly fascinating crook who had plied the forgers trade far longer than he ever admittedhis entire adult life, in factand with astonishing success. Through interviews with the descendants of Van Meegerens partners in crime and three years of archival research in the Netherlands, the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, I learned that Van Meegeren worked for decades with a ring of shady art dealers promoting fake old masters, some of which ended up in the possession of such prominent collectors as Andrew Mellon and Baron Heinrich Thyssen. All the while, Van Meegeren cultivated a fascination with Hitler and Nazism that, when the occupation came, would provide him entre to the highest level of Dutch collaborators.

Art fraud, like other fields of artistic endeavor, has its own traditions, masters, and lineages. When Van Meegeren entered the world of forgery, he joined a preexisting culture of illicit commerce that had thrived in Europe and America for years and would continue to thrive throughout the first half of the twentieth century, a time when the market for old masters was booming thanks to a growing number of buyers ready to dedicate their newly made industrial fortunes to the collecting of fine pictures. Not only was Van Meegeren an important player in an elaborate game of international deception in the 1920s and 1930s, but some of his disreputable associates later put their expertise to work laundering stolen Holocaust assets in the same way they had laundered fake picturesthrough the art trade. Although Van Meegeren himself stuck mostly to the sale and promotion of forgeries, he and his circle offer a case study in opportunism: for during the war, they operated at various points along the gray scale of collaborationfrom gray, to grayer, to truly darkas they cashed in on the Nazi takeover.

Just how big an operation was the early, unknown phase of Van Meegerens career? About as big as art fraud gets. The picture swindles with which Van Meegeren was involved during the 1920s were remarkable both for their financial scale and for the numbers and types of people involved. The following incident, never before disclosed, offers a glimpse of Van Meegerens unlikely team of accomplices.

In the spring of 1928, Van Meegeren, then thirty-nine years old and just coming into his own as a forger, paid a discreet two-week visit to London, where he stayed with a friend by the name of Theodore Ward. An industrial chemist who specialized in the technology of paint, Ward was also an avid collector of old masters, particularly still lifes by Dutch Golden Age artists like Willem Kalf and Abraham van Beyeren. He bought, sold, and traded such pictures; he haunted the salesrooms at Christies and Sothebys; and hardly a single item of quality ever came through the galleries of Bond Street without attracting his inquisitive eyes. Ward later donated his still lifes to the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford in memory of his wife, Daisy. Today, the Ward collection is generally recognized as one of the most comprehensive of its type in the world.

Inspired by his boundless zeal for Holland and its artistic achievements, Ward had even created an ersatz seventeenth-century Dutch interior in the parlor of his Finchley Road townhouse. With the distinctive black and white stone floors, rustic ceiling beams, and sturdy oak furniture typically found in pictures by De Hooch, Vermeer, and Metsu, the Ward residence looked almost like a stage set awaiting costumed performers to enact familiar scenes from the history of arta woman reading a letter, a sleeping servant, the mistress and her maid. Such an artificial atmosphere can only have delighted the visiting Van Meegeren, whose line of work entailed a very similar type of historical fakery.

The interior of Wards Finchley Road residence

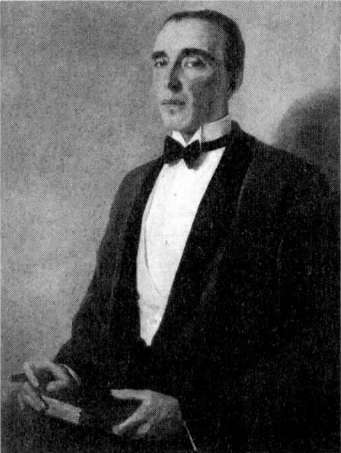

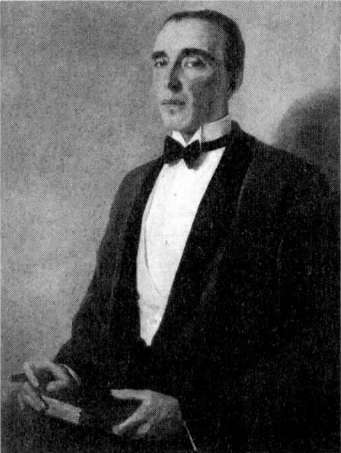

Portrait of Theodore W.H. Ward, 1928

While in this strange fantasy environment, Van Meegeren painted Wards portrait. Shown wearing a red velvet smoking jacket, cigar duly in hand, Ward looks, in the finished image, much the way members of his family often described him: sophisticated, self-assured, even a tad superior. In 1997, Wards son gave the portrait to the Ashmolean, sending with it a note in which he recalled, across a distance of seventy years, Van Meegerens frequent visits, throughout the 1920s, to the old house in the Finchley Road. Van Meegeren was very amusing, he remembered fondly, because my father was aware of his tendency to paint under another nameand quite successfully! It was then an open joke between him and my father and mother.