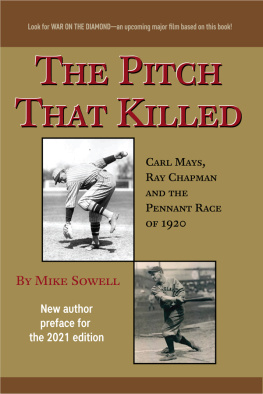

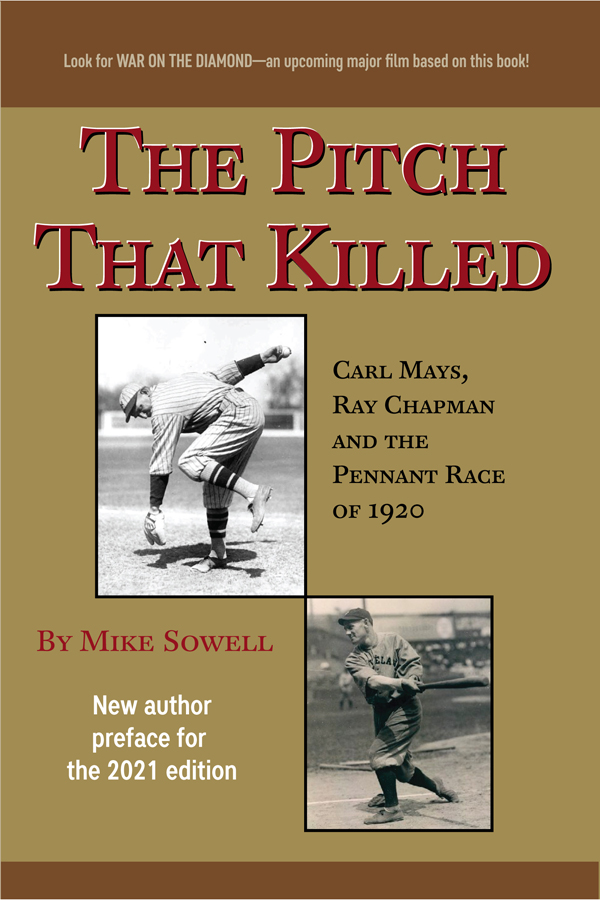

The

Pitch

That

Killed

About the Author

Mike Sowell is former sports writer in Texas and Oklahoma and the author of three baseball books, two of which were named New York Times Notable Books of the Year. A graduate of Bellaire High School in Houston and the University of Oklahoma, Sowell served in the U.S. Army from 1970 to 1972.

His first book, The Pitch That Killed, was published in 1989 and was the winner of the CASEY Award for best baseball book of the year as well as a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. July 2, 1903: The Mysterious Death of Hall-of-Famer Big Ed Delahanty was published in 1992 and One Pitch Away, also a New York Times Notable Book of the Year, in 1995.

Sowell later spent 15 years on the faculty at the Oklahoma States School of Journalism & Broadcasting, later the School of Media & Strategic Communications. He was inducted into the Oklahoma Journalism Hall of Fame in 2007. He now is retired and lives in Tulsa, Oklahoma, with his wife, Ellen.

The

Pitch

That

Killed

Carl Mays, Ray Chapman

and the Pennant Race of

1920

Mike Sowell

Copyright 1989 Mike Sowell

Epilogue 2015 Mike Sowell

Published by Summer Game Books at Smashword

First eBook edition 2015, by Summer Game Books

First Summer Game Books paperback edition published 2021.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission from the copyright owner and the publisher. The replication, uploading, and distribution of this book via the internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher, is illegal.

ISBN: 978-1-938545-42-9 paperback

ISBN: 978-1-938545-72-6 ebook

For information about bulk purchases or additional distribution, write to Summer Game Books

P. O. Box 818

South Orange, NJ 07079

or contact the publisher at

www.summergamebooks.com

In memory of my father,

Dr. Leon B. Sowell

Acknowledgments

First of all, I am indebted to Tom Heitz, the librarian at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, and his staff for their cooperation and assistance whenever it was needed, and to Lloyd Johnson, formerly the historian at the Hall of Fame Library and now the executive director of the Society for American Baseball Research.

When I began my research in 1985, I was fortunate to make the acquaintance of Ray Chapmans sister, Mrs. Margaret Joy of Huntington, West Virginia. Her memories of her brother, the materials she provided, and her friendship proved to be invaluable over the long months ahead.

A number of other people deserve recognition for helping make this work possible. Jay Cronley gave me advice and encouragement when it was needed. Tom Lindley provided assistance with editing, and Gerald Locklin was the first to read the completed manuscript. Bob Gregory shared his insight and helped keep up my confidence. Steve Love and Kathy Bliss sent photocopied materials whenever requested. I also want to thank my agent, Mel Berger, and my editor, Rick Wolff. And I am grateful to Justin and Russell for their endurance, to Pat for his unfailing support, to my mother for all she has done over the years, and to Ellen, who was at my side from the day the research began to the day the writing was completed.

Contents

Preface to the 2021 Edition

It has been more than 100 years since Ray Chapman, a star shortstop for the Cleveland Indians, died as a result of being hit by a pitch ball in a game against the New York Yankees. It happened on August 17, 1920, and more than 25 million pitches later in Major League Baseball games, no other player has sustained the same fate.

The story of Chapmans beaning by Carl Mays and its fallout originally was published by Macmillan Publishing Company in 1989, and it has remained in print since with various publishers. This edition by Summer Game Books in 2021 comes the same year as a documentary based on The Pitch That Killed will be released. War on the Diamond, directed by Emmy Award winner Andy Billman, will examine the events leading to the fatal pitch and its repercussions, including a now century-long rivalry sparked by the events of 1920 involving Mays and Chapman.

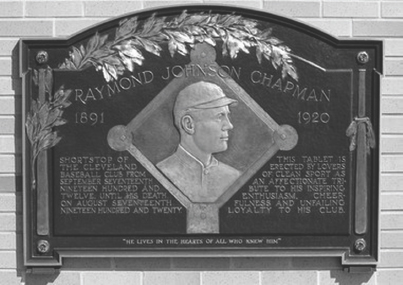

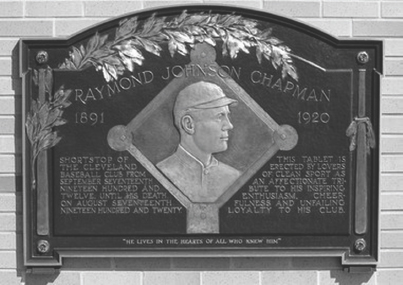

There also has been an interesting addition to the story. The 175-pound bronze plaque Cleveland fans bought to pay tribute to Chapman originally was displayed at League Park and later at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. However, the plaque was taken down and misplaced. It went missing for decades before being discovered in a storage room at Jacobs Field in 2007. Now the plaque honoring Chapman resides at the entrance of the teams walk-through display beyond the center field fence at the clubs new home, Progressive Field. The inscription reads, He lives in the hearts of all who knew him.

As proof of that statement, Cleveland fans continue to pay tribute to Chapman by visiting his grave at the citys Lake View Cemetery, leaving baseballs, bats and other mementos to the ballplayer. These items serve as fitting tributes to keep alive the memories of both Chapman and Mays, the unfortunate players involved in the sports greatest tragedy.

Both men were victims of that one pitch on August 16, 1920. Ray Chapman lost his life. And Carl Mays lost his reputation, now remembered not as the great pitcher he was, but as the man who threw the only pitch in major league history that killed a fellow player. This book tells their story.

Mike Sowell

March 2021

You simply cant get out of the way of the bean ball, though you see it coming and you know its going to crash into your skull. I can still remember vividly how I was fascinated by seeing that ball coming toward my head. I was paralyzed. I couldnt make a move to get out of the way, though the ball looked big as a house. I imagine that a person fascinated by a snake feels much the same way, paralyzed and unable to dodge the deadly serpent about to strike.

The ball crashed into me. It sounded like a hammer striking a big bell. Then all went dark.

Terry Turner

former Cleveland infielder

Cleveland Press

August 17, 1920

Prologue

As the Reverend Dr. William A. Scullen stood to deliver his eulogy, he paused to survey the scene in front of him. There were people occupying every available foot of space in the large cathedral, including the aisles, the sanctuary, and the communion rail. On the altar steps, a small crippled boy sat looking up at the reverend.

It was estimated that two thousand people were inside St. Johns Roman Catholic Cathedral in Cleveland that day. Another three thousand had been turned away for lack of space, and they now congregated on the steps or the nearby sidewalks. Some even used automobile tops or stepladders to get to the windows, where they could look in at the proceedings.

The people had begun arriving at the cathedral long before the service was scheduled to begin at 10:40 A.M. They had continued to arrive throughout the morning even as there was no more space for them, and now the onlookers, many with tears in their eyes, lined both sides of Superior Avenue and East Ninth Street for as far as one could see from the church doors. Patrolmen and mounted police guarded the streets in an effort to keep them open to traffic.

Next page