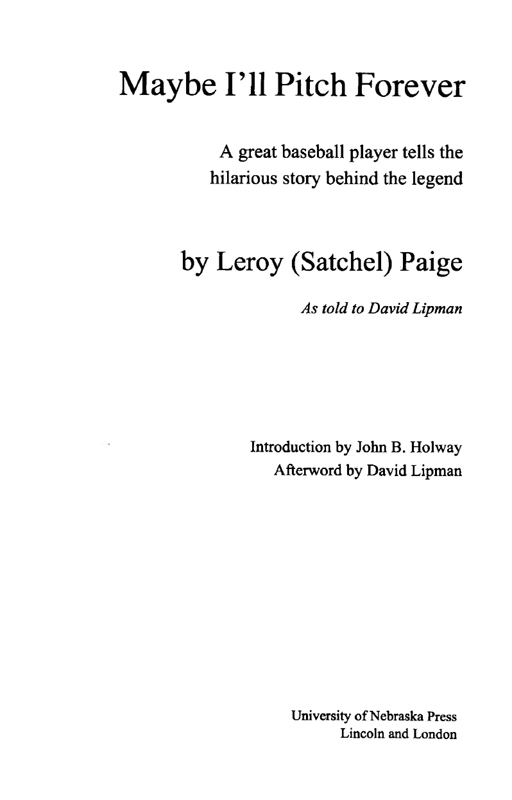

Introduction and afterword 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

First Bison Book printing: 1993

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Paige, Leroy, 1906

Maybe Ill pitch forever: a good baseball player tells the hilarious story behind the legend / by Leroy (Satchcl) Paige, as told to David Lipman; introduction by John B. Hoi way; afterword by David Lipman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-8732-7 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-8795-2 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-8796-9 (electronic: mobi)

1. Paige, Leroy, 1906-2. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiogra phy. I. Lipman, David. II. Title.

GV865.P3A3 1993

796.357092dc20

[B]

92-35221 CIP

Originally published by Doublcday & Company in 1962.

Reprinted by arrangement with David Lipman, represented by McIntosh and Otis, Inc.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Introduction

by John B. Holway

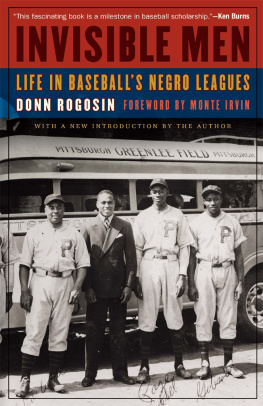

I first saw Satchel Paige on a muggy May night in 1945. He was pitching for the Kansas City Monarchs against Josh Gibsons Homestead Grays. I was one of thirty-thousand fans packing Washingtons old Griffith Stadium to watch the duel, and I remember Satch taking his famous windmill windup for two innings before retiring.

None of us, including Satch or me, even guessed that within six months sixty years of apartheid would be swept away with the revolutionary signing of Jackie Robinson. And, though no one thought of him that way, the Satch who stood in the middle of the diamond that night was a leader of the revolution. For, without Satchel Paige, there just might not have been a Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn.

Satch himself followed Robinson into the major leagues, and in October 1948 I joined eighty-seven thousand fans in Clevelands Municipal Stadium to see him pitch in the World Series. By then he had entered white history, with all its statistics and records. Before then, he had lived his life as a mythic figure in black legends passed along orally by the griots of baseball.

Not only was Paige an amazing athlete, he was one of the great American humorists in the tradition of Mark Twain, Will Rogers, and Yogi Berra.

It is this figure, the most famous black player of his eraand still the most colorful everwho shines through the pages of this remarkable autobiography, Maybe Ill Pitch Forever . He almost did. He pitched his first professional game in 1926 and his last one almost forty years later, in 1965 for the Kansas City Athletics.

Today, more than four decades after his Cleveland Indian debut in 1948, we have added the black records and statistics to fill out the legend. Now the official Macmillan Encyclopedia lists all the wins and losses, strikeouts and walks, of Paiges amazing career, the Negro League stats and the American League stats alike. (Of course some Negro League games were not reported and will never be found, but a large body of numbers has been rescued.)

How old was Paige? He gave so many contradictory dates for his birth that a teammate finally asked how old he really was. As old as [Indians owner] Mr. Veeck wants me to be, Satch replied.

After a year in the black minor league at Chattanooga, Paige pitched his first big league game for the Birmingham Black Barons on July 3, 1927, at the presumptive age of twenty-two. The game was played in Detroit, and Satch was knocked out of the box in the second inning. Two weeks later he beat the Memphis Red Sox 12-1, and he never looked back.

With two older men, Sam Streeter and Harry Salmon, teaching him control, the wild youngster could soon throw a ball over a Coke bottle cap and, in his own words, nip frosting off a cake. Paige bounced along the early highways of America packed in a roadster, sleeping with his knees up against his chin, and keeping the club loose with tunes on the Jews harp. He was a great musician and in later years loved to strum the ukelele and lead his teammates in songs or harmonize with the radio favorites, the Mills Brothers.

Satch won eight and lost three in the second half of the year, leading the Barons from fifth to the second-half flag. If they had given out Rookie of the Year Awards then, hed have surely won it. Twenty-one years later, when he was named American League Rookie of the Year, he asked, What year?

The next year, 1928, Satchel won twelve and lost four. (The Negro Leagues played about eighty games a year then, and not all of the games have been found.) He boasted a variety of pitchesthe Midnight Creeper, the Four-Day Rider, the Be Ball (It be where I want it to be)but, whatever their names, they were all fastballs. He changed the size of the ball, said old-time sports writer Eric Ric Roberts. Old-time batters variously described the balls he whizzed by as white dots or white marbles. That last one sounded a little low, didnt it, ump? one hitter protested. He threw fire, whistles Hall of Famer Buck Leonard, who says he didnt get a hit off Paige in seventeen years.

Satchel raised his foot up to hide his face before he let go. The batters said he had FAST BALL written on the sole, but they still couldnt hit it; they knew what was coming, but not where.

He threw overhand, sidearm, and underhand. He occasionally threw his Little Tom, or change-up, and later even experimented with a Wobbly Ball, or knuckler.

When he was inducted into Cooperstown in 1971, Paige declared that there were many Satchels, there were many Joshes in the Negro Leagues. He faced some of the best players in Americahitters like Mule Suttles and Turkey Steames, and pitchers like Big Bill Foster and Bullet Joe Rogan. The latter, he acknowledged, was the greatest until I came along.

In 1929 most of the Barons stars left, including his favorite catcher, Bill Perkins. Satchels won-lost dropped to 11-11, though he did strike out seventeen men in one league game, which was one more than the white major league record at that time. In all, he whiffed 184 men in 196 innings to set a Negro League record that was never broken.

As the Great Depression struck in 1930, the Kansas City Monarchs unveiled a revolutionary portable lighting system, which would save the Negro Leagues in the decade of hard times ahead. Satchel jumped to the Baltimore Black Sox to try to make some extra bucks. There he met the great black-Indian pitcher, Smokey Joe Williams of the New York Lincolns (originally from Lincoln, Nebraska). Joe was either in his forties orfifties and still winning ball games. The arguments over Joes age probably inspired Satchels own public relations guessing game after he reached the Indians. He found no gold in the East, however, so he returned to Birmingham. His combined record for the year was 12-5.

In 1931 Satchel jumped again, to the Cleveland Cubs, who played a block away from the Indians home, League Park, which was closed to him, of course. Then the flamboyant Gus Greenlee signed him for the new Pittsburgh Crawfords, where he would soon be united with Josh Gibson in the greatest battery in baseball history.

That winter Satchel traveled to California. In one game against big leaguers Frank Demaree, Wally Berger, Babe Herman, and others, Paige, after hearing a racial slur, ordered his fielders to sit down, and struck out Demaree and Berger. His catcher, Larry Brown, confirmed the tale. Satch, youre the biggest fool ever Ive seen in my life, Larry chortled. I never saw anybody but you do that with a one-run lead. They were invited to play in San Diego provided that Satchel put on a good exhibition. God damn! Larry exploded. Thats all Satchels got , is a good exhibition!