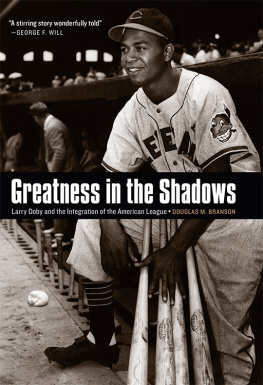

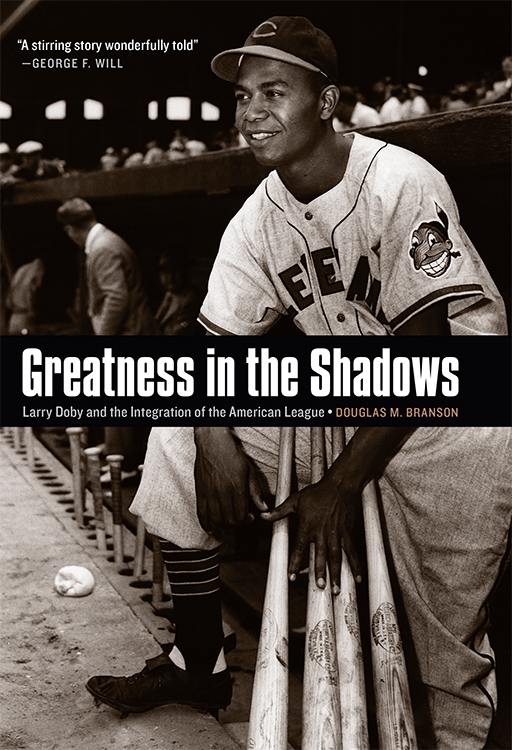

Eleven weeks after Jackie Robinson stepped onto the grass at Brooklyns Ebbets Field and into American history, Larry Doby joined the Cleveland Indians, becoming the first African American in the American League.... Dobys trials, and the triumphs that earned him a place in Cooperstown, are a stirring story wonderfully told by Douglas Branson.

George F. Will, syndicated columnist for the Washington Post and author of Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball

Douglas Bransons new book on Larry Doby is a must-read for anyone who cares about the Jackie Robinson story and the integration of baseball. Doby has been neglected for far too long, so its exciting to see Branson give Doby his due.

From Bill Veeck to Reggie Mantle and Willie Mays, Douglas Branson examines and contextualizes Larry Dobys contributions to the game during a time when baseball captivated the country. Bransons personal memories of his subject add depth to a well-researched account.

Greatness in the Shadows

Larry Doby and the Integration of the American League

Douglas M. Branson

University of Nebraska Press| Lincoln & London

2016 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image Granger, NYC, all rights reserved

Author photo courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law

Unless otherwise noted, illustrations in the gallery are courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Branson, Douglas M.

Title: Greatness in the shadows: Larry Doby and the integration of the American League / Douglas M. Branson.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015031802

ISBN 9780803285521 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9780803285941 (epub)

ISBN 9780803285958 (mobi)

ISBN 9780803285965 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Doby, Larry. | Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. | African American baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. | Discrimination in sportsUnited States. | American League of Professional Baseball Clubs. | BaseballUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC GV 865. D 58 B 73 2016 | DDC 796.357092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015031802

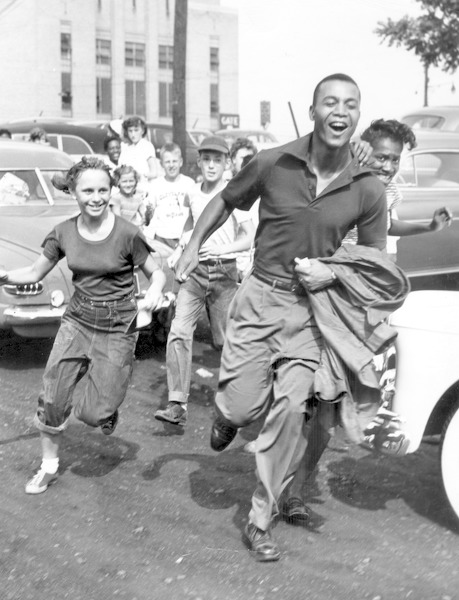

Frontispiece courtesy of the Cleveland Press Collection, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To two other professor-authors of baseball books whose efforts inspired my own

Robert Francis Garratt

Joseph Thomas Moore

Contents

It would really disturb me if I went into a locker room and found a black player who didnt know what players like Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and Don Newcombe did forty or fifty years ago.

H ENRY A ARON , introduction to Robinsons I Never Had It Made

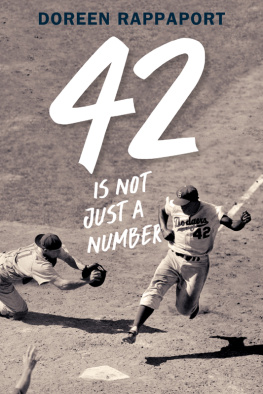

The 2013 film 42 is the most recent Jackie Robinson movie, one of several made over the years. It is worth the wait, said Sports Illustrateds review of the film. In addition to feature-length films, there have been three made-for- TV movies, one Broadway play, and fifty-plus book-length biographies of Jackie Robinson, who played second and third base for the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1947 to 1957.

Robinsons pathbreaking accomplishments are memorialized in other ways. Every April all Major League Baseball players wear number 42 in honor of his achievements, something they have done since the inaugural Jackie Robinson Day in 2004. Robinson was a six time All-Star, elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, the first year in which he was eligible.

Robinson was the first African American to play Major League Baseball in the modern era, breaking into the big leagues on April 15, 1947. In a country where both overt and latent racism were still nearly universal, he endured taunts, epithets, vituperation, hostility, and death threats along with threatened and real acts of physical intimidation. He put up with it all, initially alone, with aplomb and dignity while achieving Hall of Fame numbers, batting .311 lifetime, with 127 home runs. He carried himself with class and dignity, but after two years of relative silence, he became an articulate, sometimes angry spokesperson for integration not only in baseball but also in the larger society.

Larry Doby, center fielder for the Cleveland Indians, was the second African American to break the color line, just eleven weeks after Robinson, on July 5, 1947. Doby too endured taunts, second-class-citizen status, hostility, avalanches of bottles and cans thrown onto the field, and other acts of physical intimidation. He was not allowed in many of the hotels in which the Indians stayed, including, until 1954, the lodgings for each years Indians spring training, in Tucson, Arizona. In certain southern cities, where the Indians would play a number of preseason exhibition games, cab drivers would not permit Doby to ride in their whites only taxis. At times Doby was forced to walk to the ballpark where the Indians were to play. Once he was there, on several occasions ushers and turnstile operators denied him admission to the park because he was black. Some ushers tried to bar him from the park even when Doby was in his Cleveland Indians uniform.

In contrast to knowing about Jackie Robinson, virtually no youngblack or whitebaseball players or fans know who Larry Doby was. So, too, the middle-aged are ignorant of what a great player and good man Doby was, let alone what he endured in integrating the other conference of Major League Baseball, the American League. The books on Jackie Robinson continue to come forth with one appearing even as this Doby book was being written. Meanwhile, the memory of Larry Doby and what he accomplished is forgotten, or at least has faded away, much like an iceberg drifting into more temperate waters and melting to nothing.

Writing of the great Chicago Cub, Ernie Banks, Rich Cohen, a supposedly knowledgeable Sports Illustrated baseball writer, asserts that along with [Hank] Aaron and Willie Mays, Banks forms a triumvirate of African-American pioneers who came up in the aftermath of Jackie Robinson, who were counseled by Jackie and rode his break through weird old racist America.

Doby batted .286 in nine seasons with the Cleveland Indians (.283 overall, in a fourteen-year career), with 253 home runs. He was a seven-time All-Star (Robinson was six-timer), elected to the Hall of Fame as wellbut only in 1998, and only then by the Veterans Committee (rather than by the Baseball Writers of America), many years after Doby had become eligible. He twice led the Indians to the American League pennant (1948 and 1954).

It would be more poignant to say that no books have been written about Doby, but there has been one, by Joseph Moore of Montclair State University in New Jersey.

But there have been no movies. Neither Major League Baseball nor the American League observes a Larry Doby Day. When in 1997 Major League Baseball required all teams to retire number 42 permanently, in honor of the long-since-deceased Robinson, neither baseball nor the news media mentioned Dobys name, let alone his achievements. Nor did the baseball powers require teams to retire the number 14, which Doby had worn. At that time, in 1998, Doby was still alive, living in Montclair, New Jersey, and busy with his children and grandchildren. On a relative basis, as compared to Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby and his baseball career have slipped into obscurity.