In The Classic Mantle, acclaimed sportswriter Buzz Bissinger tells the story of Mickey Mantles unforgettable career. Long considered one of baseballs most memorable figures, Mantle spent his entire eighteen-year career, from 1951 to 1968, with the New York Yankees, winning three American League MVP titles, playing in twenty All-Star games, and winning seven World Series. Today, more than forty years after his retirement, he still holds six World Series records, including the one for most home runs. Bissinger goes beyond the statistics to bring Mantle to life, and stunning photographs by Marvin E. Newman make this book a fitting tribute to Mantles career and his lasting impact on the sport of baseball.

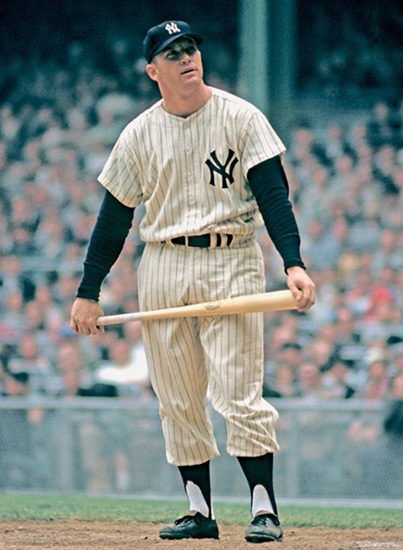

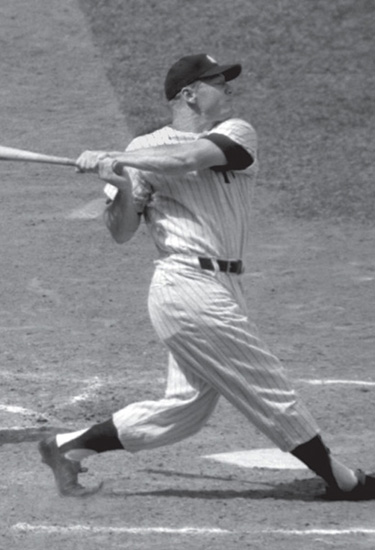

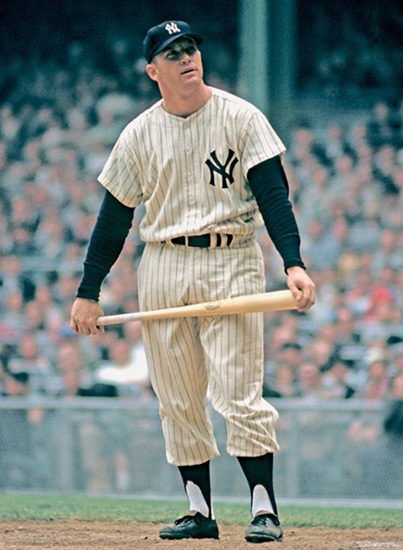

On deck waiting to hit at Yankee Stadium, 1954

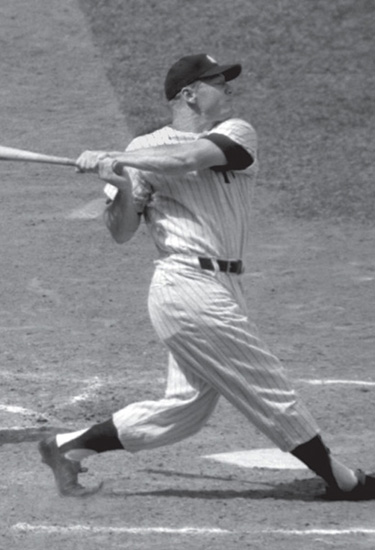

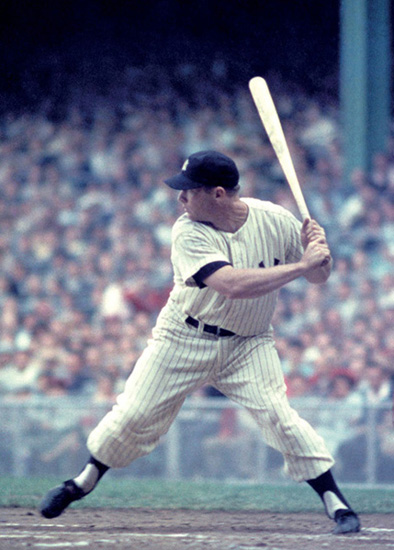

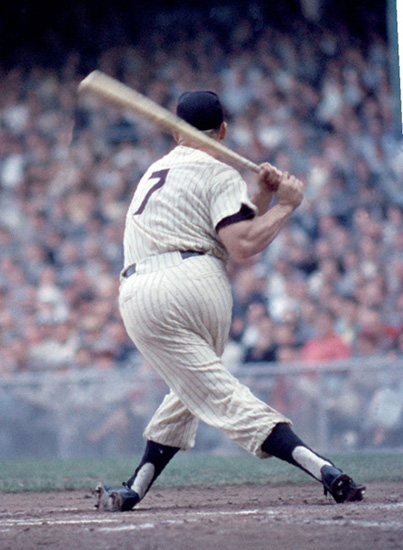

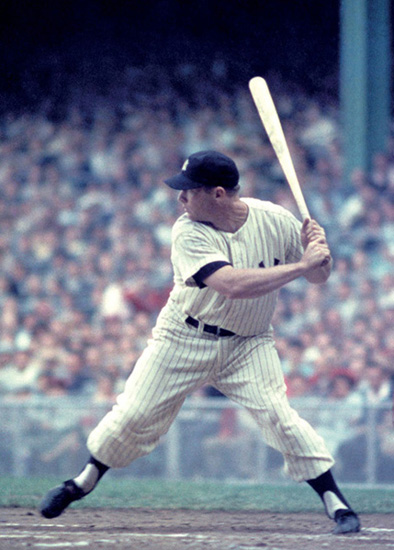

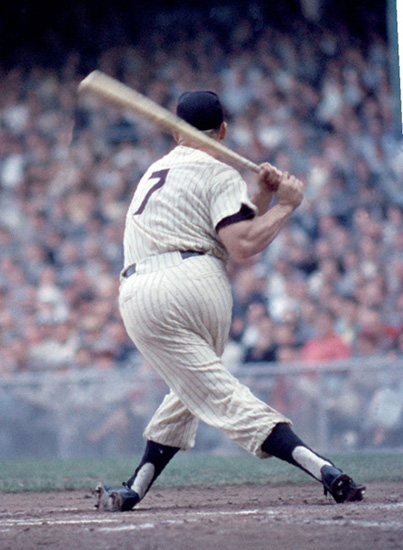

Batting left-handed, Yankee Stadium, 1955

Chapter 1

I remember the year, 1962, when I was seven years old. I know it was a Sunday in May when doubleheaders were still commonplace. I know it was my first game ever at Yankee Stadium, for me far more important than a pilgrimage to the Vatican to talk baseball with the pope. I know I was with my father. I know the opponents were the hapless Washington Senators, which meant he probably got the tickets for free. I know the seats were many rows up on the mezzanine level, leaving any ball hit to the last third of the outfield up to the imagination.

It did not matter.

In the second game that day, an easy win in which Jim Bouton pitched a complete game shutout despite giving up seven hits and seven walks, Mickey Mantle hit two home runs. I wont say I remember the trajectory of the ball, but memory isnt for literal remembrance anyway, so the arc of the ball in each instance was high and explosive, neither one a little squeaker just clearing the fence. Because in the mind of a child, the Mick never hit squeakers anyway. And most of the time he didnt.

It seemed to me on that day of May in 1962 that everything about Mantle was right, the essence of what a great baseball player should be and represent. I loved the way he looked in the on-deck circle, on one knee in rapt attention, eyes lasered on the pitcher to see what he was throwing. Like everyone else, I noticed the way he ran the bases after he hit those home runs, with his head ducked down so as not to show anyone up, but also, as if it were possible, to try not to draw attention to himself.

I knew the Mantle lore, as any baseball kid from New York didthe tape measure home run against the Senators in April 1953 that left Griffith Stadium in the nations capital and was pegged at 565 feet before it landed in a backyard; the shot in 1956, once again off the Senators, this time at Yankee Stadium, that came within eighteen inches of leaving the Stadium before it caromed off the upper-deck facade and would have traveled an estimated 600 feet had the flight been unimpeded; the shot in 1963 off Kansas City As pitcher Bill Fischer at the Stadium that once again would have been the first fair ball ever hit out of Yankee Stadium were it not for the gap of several feet to the top facade; the twelve World Series he appeared in, seven of them won by the Yankees, in which he hit 18 home runs and drove in 40 runs, both major league records; the more pedestrian dingers that routinely cleared 400 feet.

I knew he was fast, not as fast as he was at the beginning of his major league career, in 1951, when nobody had seen anyone run that fast to first base, but still in my mind fast enough. I longed to have been old enough to appreciate his greatest season ever, 1956, when he won the Triple Crown. I had followed the epic home run derby between him and Roger Maris in 1961 in which it had been assumed that Mickey would be the one to topple the Babes mark of 60 had he not gotten hurt.

Batting left-handed, Yankee Stadium, 1955

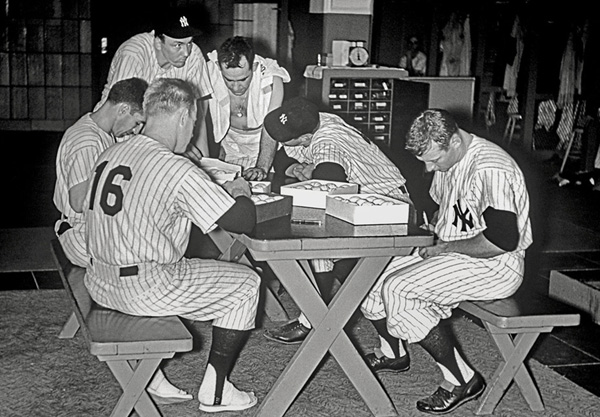

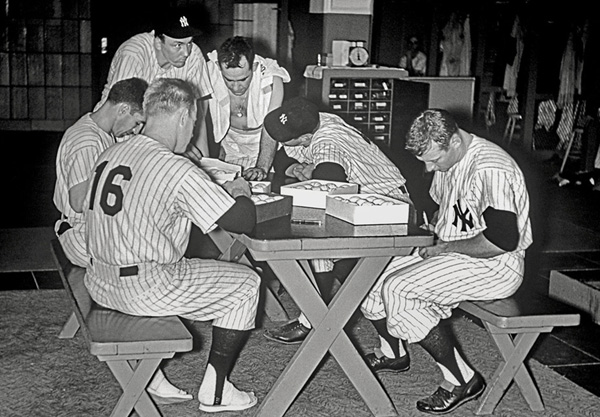

Clockwise from left: Ford (16), Rizzuto, Noren, Berra, unknown player, and Mantle, 1953

I was not aware of his legendary carousing in the 1950s with partners in crime Billy Martin and Whitey Ford and Hank Bauer. I knew nothing of his drinking. I knew nothing of his self-hatred, a man who despite all his accomplishments was as hard and relentless on himself as any man has ever been. I knew nothing of the pathos and bathos of his descent after his playing days were over and he might as well have been an unmoored buoy in an untamed sea.

But no child in the Mantle era had knowledge of any of that. In my very first game at the Stadium he did exactly what I hoped he would do, what all of us who watched him hoped he would do at any given moment.

Be epic.

Mickey Mantle has been dead for seventeen years. Given his career and life, it seems impossible that he has been gone that long. He still resonates in the public awareness, has a front-of-the-line place, unforgotten like virtually all other sports figures are inevitably forgotten. You can still see the all-American blond hair and shy smile of a boy from Oklahoma who conquered not only the greatest city in the world but also the worlds toughest collective critics in which his mission, even if he chose not to accept it, was somehow to replace the great DiMaggio in his mansion of center field in the early 1950s. You can still see the gaunt frame withering into death as the cancer ate through him, when the smile, no longer boyish, had the poignancy of tragedy and regret but also dignity.

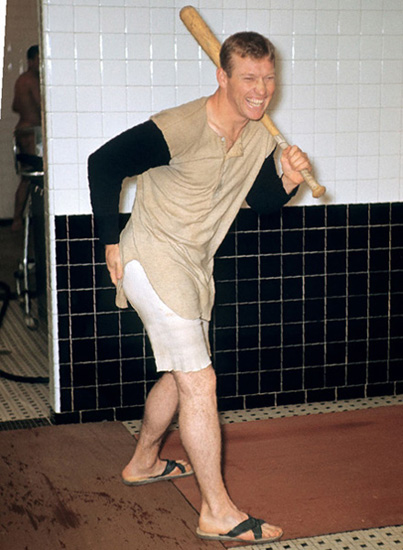

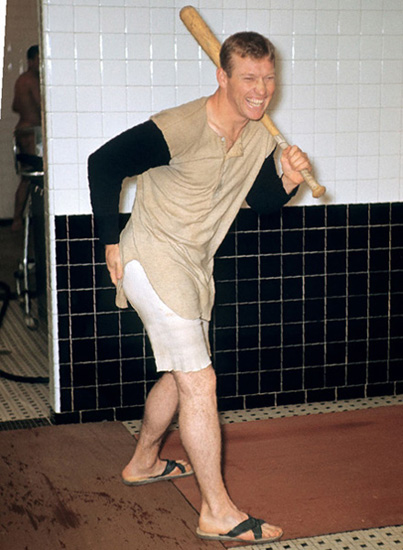

At bat in a toy ball game, Yankee Stadium locker room, 1955

Batting left-handed, Yankee Stadium, 1955

And, of course, you can still see the number 7 etched into the blue pinstripes of his uniform like the brightest star, a talisman of the supernatural. You can still see the monstrous back-to-front swing, where nothing was ever left out. And you can still see those home runs like the instant formation of the biggest rainbow, flying into the sky to shove aside the Big Dipper. The Natural? The comparison has been made a million times. But he was the Natural in every way possible, on the field and off of it.

Certainly Mantles play in the caverns of old Yankee Stadium did make him unique, more than unique, right up there with DiMaggio and the great ghosts of Ruth and Gehrig when he was anywhere close to healthy, which he never really was, going back to his days as a teenager. He deserves his place among the center-field monuments. He always played hard despite constant and unimaginable pain in his legs. He even played well when he was miserably hung-over, mustered by his cantankerous manager, Casey Stengel, to pinch-hit in the seventh of one game, even though the vapors of alcohol carried to Queens, and still able to hit a home run. He was a switch-hitter thanks to his father, Mutt, who started to teach him how to bat from both sides of the plate when he was four. There was the incomprehensible speed in addition to the incomprehensible power despite chronic osteomyelitis, a bone infection in his left ankle stemming from being kicked above the shin in a high school football game.

Next page