For Holly, with love

Contents

Foreword by Marty Appel

My favorite story from 1951 involves the Bobby Thomson game and one Yogi Berra.

The 51 season featured a terrific American League pennant race, and a similarly terrific one in the National League, where those other two New York teamsthe Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giantsneeded a three-game playoff to decide a champion.

A number of New York Yankees players went to the third game at the Polo Grounds. Among them was Mr. It aint over til its over himself, Lawrence Peter Berra.

But it turned out that Yogi left the game early to beat traffic and missed the Shot Heard round the World, the Thomson homer. Oh boy.

He didnt follow his own advice. It was one of the few times he got anything wrong.

Sometimes the baseball gods are especially good to us.

To show approval of the line of continuation that is part of the game we love, they will, from time to time, give us one immortal coming and one immortal going as teammates. So we see Ted Williams, circa 1939, in the same Fenway Park dugout with Lefty Grove. Tom Seaver with Roger Clemens in 1986. Phil Niekro as a Milwaukee teammate with Warren Spahn in 1964. Reggie Jackson with Mark McGwire in Oakland in 87. Or the Yankees Don Mattingly and Derek Jeter passing in the night, in 1995.

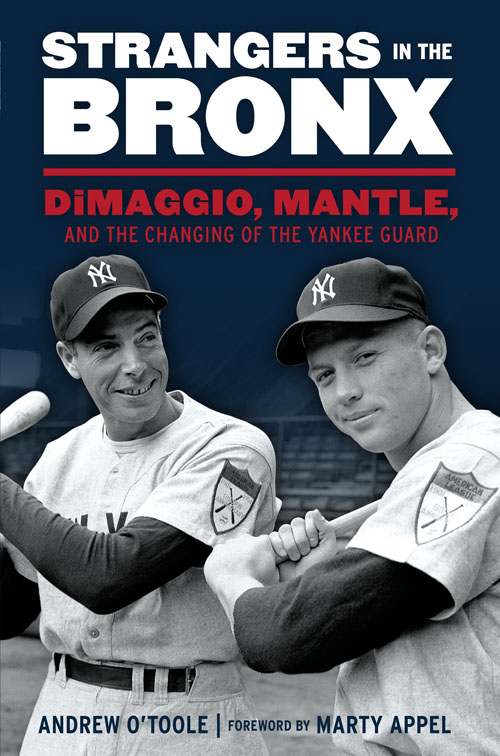

Joe DiMaggio was a teammate of Lou Gehrig in his final seasons, and then Mickey Mantle was there in Joes farewell season of 1951.

And that brings us to the events captured by Andrew OToole in this book. Because not only were Joe and Mickey touching, as in Michelangelos fresco of the creation of Adam, but baseball fans had a sense of what they were witnessing. This wasnt a random event. People knew that Mantle was something special, and they also knew that the magic that was Joe DiMaggio was fading. They just didnt know for sure that Joe was playing his last year of ball (his term for baseball.)

Mick was the proverbial highly touted rookie, but the clich barely does him justice. He wasnt on the roster when he went to Casey Stengels instructional school and then spring training in 1951. He hadnt played Triple-A ball, and he was still a teenager. Yes, his was a name to file away for future reference.

But Casey saw it differently. He saw a raw talent, still without a position, who had such natural gifts that the temptation was there to give the kid a shotright then. The Yankees were overloaded with outfield talent, but so what?

Casey got this one right.

Fans also knew that they were seeing them both at a very special time in Yankee history, as the team advanced to a third consecutive world championship. Casey may have arrived with the reputation of being a clown, but by 1951 that was all in the past. The winner of two straight titles was already a genius so far as baseball was concerned, and a master of maneuvering his players so that he seemed to be playing with a 35-man roster while everyone else had 25.

The Yankees were so loaded at this point in their history that by the end of the decade, almost every team in the league had a first-string catcher who came from the Yankee organization, and plenty of other players as well. There are a lot of peaks in Yankee history, years of such amazing dominance that many run together as one. But 1951, largely due to the crossing of Joe and Mickey, occupies a special standing among Yankee seasons.

Dont leave early on this story. There are plenty of twists and turns en route to glory.

Yogi would be well advised to read it all.

Marty Appel

Preface: To Be Young and a Yankee

Trust the art, not the artist.

I first heard those words uttered years ago by a musician I admire a great deal. The sentiment struck me at the time and the refrain has replayed in my mind on many occasions since.

Art and artist may not necessarily translate to the world of sports, but public fascination with celebrity most certainly does.

As a child, one particular athlete captured my imagination. Indeed, the love an eight-year-old boy has for his favorite baseball player is a special relationship. In my case, my adoration was directed at a free-swinging, perpetually smiling Panamanian catcher: Manny Sanguillen. I took on Sangys personality when playing sandlot ball, his mannerisms, his batting stance, as well as Mannys philosophy at the plate, which meant I swung at everything. A notorious bad-ball hitter, when asked why he swung at so many pitches out of the strike zone, Sangy replied, Because it feels good! Such an attitude frustrated my Little League coaches but did much to enhance my enjoyment of the game.

And then, on November 5, 1976, my hometown Pittsburgh Pirates traded Manny and cash to the Oakland As for Chuck Tanner a manager!

I was 10 years old, and upon learning that Sangy was no longer a Pirate, my innocence was forever lost. Nearly 20 years later I had the good fortune of meeting Sanguillen while working on my first book. The two of us sat behind the third-base dugout inside a virtually empty Pilot Field in Buffalo. Sangy put his arm around the back of my seat and graciously answered my questions. For the better part of an hour he was engaging and ebullient. I walked away from the interview gratified that my baseball idol did not disappoint.

Through the years Ive done extensive study on sports history, and I have come to learn that not all idols were quite as affable as Sanguillen

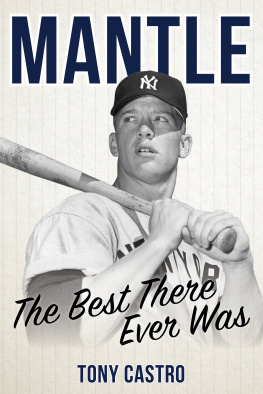

I dont remember exactly how old I was the first time I read my brothers battered copy of Ball Four . But I was young, and I recall being enraptured with Jim Boutons journal of the 1969 Seattle Pilots season. At the time of publication, Ball Four famously shocked the reading public with behind-the-scenes escapades and sundry stories of Boutons current and past teammates. It was the tales which involved Boutons former Yankee teammate Mickey Mantle that garnered the most attention. Bouton portrayed a Mantle whose nocturnal escapades flew in the face of his All-American image, as well as a baseball hero who occasionally displayed boorish behavior toward his fans.

Ball Four did not sour me on the game or the men who gloriously displayed their skills on the playing field. In fact, I came to appreciate the game even more. Bouton simply revealed a truth that needed to be explored; outside of their athletic ability, our sporting heroes are, in fact, not different than us. They endure the same struggles with mortality and suffer from the same bouts of insecurity as the fans cheering in the stands. Indeed, the sole trait that differentiates them from the rest of us is the ability to hum that pea across the plate or knock the piss out of a big league curveball. This reality helped me enjoy baseball all that much more.

Joe DiMaggio It is one of the most mythic names, not only in the annals of baseball, but also in pop culture. Perhaps more than any other figure in sports history, DiMaggio isnt revered so much for what he accomplished on the field of play. Rather, we relish the idea of Joe DiMaggio. Reality can sometimes clash with our ideals. In the instance of DiMaggio, the imperfections of a prickly personality are obscured by the magnificence displayed on the emerald green fascinations of time and memory.

Mickey Mantle He was the exemplar of what so many believed a ballplayer should look like: the golden hair, the Adonis physique, and talent bursting from his every pore. Its fair to say that no single player has ever been idolized and loved by his fans in quite the fashion Mantle enjoyed and endured. Certainly he had his detractors during his career, but those countless young boys who pledged their allegiance to the Mick in the 1950s and 60s remained unflinchingly loyal to their hero. Through the good and the bad, Mantle was their guy. He was the standard by which they measured all other athletes. And, long after the days of their youth had faded, they wept when Mickey passed away.