It is not hard to believe that if Mickey Mantle had been healthy and took better care of his body, he would probably be remembered as the best baseball player ever. This excellent book proves why.

A Season in the Sun is the best book on Mickey Mantle that I ve read by some margin. It succeeds in answering the three big ques tions: how he became an icon, why 1956 was so important, and es pecially how the mythologizing of Mantle can only be understood in the context of the 1950s. Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith stitch together not only a damn good baseball storyI found the game-by-game arc very compellingbut also link Mantle to his times in a way that really makes the book stand out. Its informative, thought ful, and without being hokey or hagiographic, it is almost a love letter to a lost and often misunderstood period of baseball history.

NATHAN CORZINE , author of Team Chemistry: The History of Drugs and Alcohol in Major League Baseball

Jesus he was a handsome man How do you like your blue-eyed boy?

E. E. CUMMINGS, BUFFALO BILL, 1920

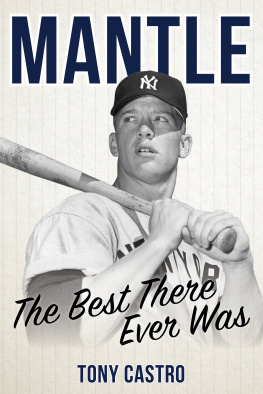

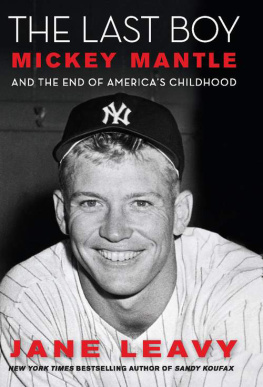

L ook at the determination on Mickey Mantles facethe resolve in his fierce blue eyes, his flexed jaw, and the hardness around his mouth. Look at the powerthe prizefighters cheekbones, the bulls neck, and the hint of a sluggers shoulders. Is it the face of weakness, the look of a man fragile enough to crack into a million pieces?

Mantles chiseled physique looked like the ideal body of a power hitter, a creation of Michelangelo sculpted out of marble. Wonderstruck by his muscled, compact frame, sportswriters and teammates tried not to stare when he ambled through the locker room, nearly naked, wearing only a towel, his perfectly V -shaped torso, barreled chest, hard stomach, and wide back on display. Built like a lead miner, with broad, sloping shoulders, bulging biceps, and Popeye forearms, Mantle was, in baseball parlance, country strong.

Hy Peskins 1956 Sports Illustrated cover photo reveals the intensity and rugged strength of baseballs most famous player. In that seasonbranded the Year of the Slugger by the magazinehis career held only great possibilities; baseball immortality itself was within his reach. His physical giftspower, speed, and agilitymade it seem like there were no limits to what he could do on a baseball field.

Yet, for all of his attributes, Mantles biographers have emphasized his overriding weakness. Too often they have presented his life as seen darkly through a rearview mirror, interpreting many events during his baseball career as a way station along the road to alcoholism. Mickey Mantle s life was spent waiting for a death that seemed just around the corner, biographer David Falkner wrote. Similarly, in her fine biography, Jane Leavy observed, Mantle fit the classical definition of a tragic hero. By the summer of 1995, alcohol-induced cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis C, and cancer had left him a shell of the man he had been in the 1950s, when, strong and tanned, he had graced the cover of American magazines and thrilled baseball fans on the diamond. Only later would his heavy drinking define the arc of his life.

This approach ignores much of the joy of his lifethe joy he discovered in the game and the joy spectators experienced watching him play. To fully understand the man, his impact on baseball, and what he meant to America, it is necessary to look at his life as he lived it, not as a study in retrospection. That means returning Mantle to the 1950s, when he became the most celebrated athlete in the country and reigned as the king of the National Pastime.

In 1956, only injuries stood between Mickey Mantle and greatness. The Mantle the fans knewthe one they saw at Yankee Stadium, watched on television, and read about in Sports Illustrated was not a drunk. He was a latter-day legend.

I N THE LORE OF Mickey Mantle, it is an often-told tale. As well it should be. Its a story of two of the greatest playersand arguably the two most iconicof the early postWorld War II era, set against the backdrop of the excitement and pageantry of a Subway Series between the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers, at a time

Before the 1952 World Series, Yankees manager Casey Stengel cornered his young center fielder for a lecture on the wily habits of Dodgers star Jackie Robinson. Jackie, Stengel explained, was the most aggressive base runner in the game. He was known for stretching a single into a double or blazing around second to turn a double into a triple. In a primal sense, he challenged the manhood of outfielders, calling into question whether they had the talent and the nerve to throw him out. Mickey listened, knowing he had the arm. But the nerve that was another matter.

In the eighth inning of Game Three, with the Dodgers leading the Yankees 21, Robinson ripped a low line drive into center field. Charging down the first base line, he reached full speed in three strides. Rounding first, his spikes kicking dust, he challenged Mantle, who fielded the ball on one hop. Suddenly the game became a chess match, a test of wits between the young outfielder and an experienced, daring base runner.

Holding the ball shoulder high, Mantle eyed Robinson, who had slowed to a dance between first and second. Mickey cocked his arm as if he were going to fire it toward first, daring Jackie to make a move. Robinson hesitated, then streaked toward second. Mantle had conned him into running for the extra base and then threw him out by what seemed like half a city block. When it was over Jackie smiled and tipped his cap. Mickey grinned. He had outsmarted the great Jackie Robinson.

On the games greatest stage, Mantle demonstrated that he had the intelligence, instincts, and ability to make the play. No wonder he recalled it as one of his most treasured memories. No wonder his biographers and a legion of sportswriters have fondly recounted the episode. Some consider it one of his greatest World Series plays. As much as his tape-measure home runs, it signaled the arrival of Mickey Mantle, the Wonder Boy of the 1950s.

Its a marvelous story. There is only one small problem with the tale. It never happened.

Mickey did not bait and trap Jackie. Robinson did not attempt to reach second. In fact, he advanced to third base on a single by Roy Campanella and then scored on a hit by Andy Pafko. The Dodgers won the game and took a 21 lead in the series. Anyone reading the New York newspapers the next day on October 4, 1952, would have seen it recorded that Robinson crossed home plate. The following spring, writing a magazine profile of Mantle, Milton Gross, an eyewitness reporter, noted that after Robinson hit the ball into center field and rounded first base, he stopped, stumbled, got to his feet again, and then scrambled back to first.

The significance of the play is not that it didnt happen but that it is remembered as if it did. Years later, Mantle confidently recalled throwing out Robinson. Ill never forget it, he said. Perhaps Mickey confused the play with a similar one in another game. But a close inspection of every Yankees and Dodgers World Series contest that Mantle and Robinson played in 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956 reveals that Mickey never threw Jackie out at second. It turns out that Mantle was an indifferent student of his own career. In that regard he was like his teammate Yogi Berra, who once commented, I never said most of the things I said.

Journalists and biographers have retold Mickeys tale, perpetuating a mythology that started with his own hazy memories. Discerning the truth of Mickeys world, especially during the 1950s, demands casting a skeptical eye on his many ghostwritten autobiographies and the popular reminiscences of the era. In reconstructing his public and private life, we visited his hometown, Commerce, Oklahoma, where the Mantle myth took shape; the Cooperstown Hall of Fame, where the legend is enshrined; and newspaper archives in New York and Washington, DC, where the story lies interred in hundreds of reels of microfilm. In Cooperstown we collected copies of team media guides, game programs, advertisements, and rare baseball magazines. Page after page, Mantle comes alive again, not brooding and pessimistic, as he is so often remembered, but hopeful and full of promise. We have sought not to judge Mickey Mantle but to reveal him as others saw him at the height of his career.