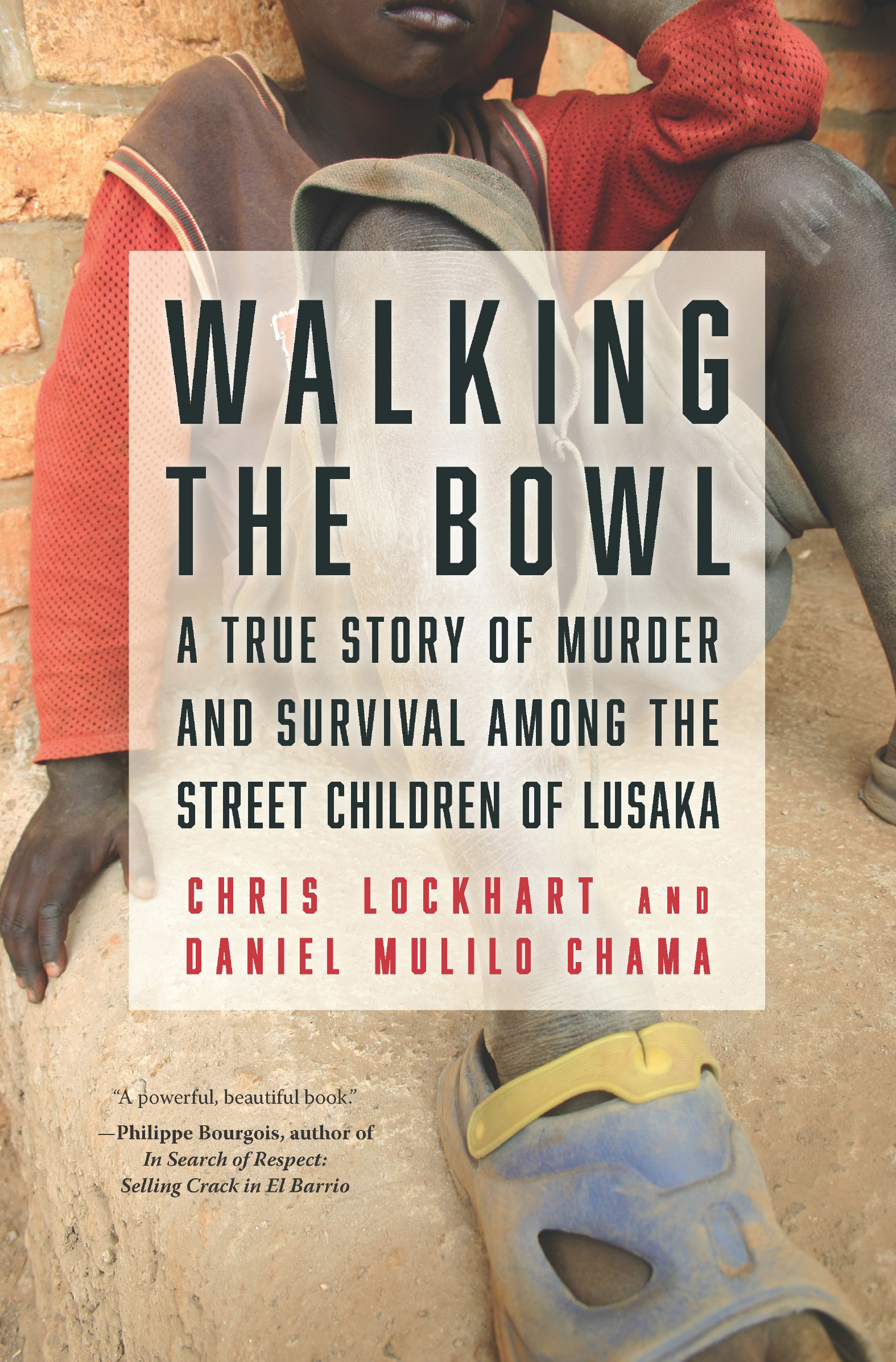

[A] transcendent study of the street children of Lusaka, Zambia... Fans of Behind the Beautiful Forevers and Strength in What Remains will flock to this riveting and deeply reported portrait of life on the margins.

Publishers Weekly , starred review

A vivid, unforgettable account of life at the margins of the margins. This book will transport you to a world you didnt know existed but that you will never fully leave behind. Chris Lockhart and Daniel Mulilo Chama have achieved something extraordinary: reporting so deep that youll want to read passages again and again, combined with storytelling so propulsive that youll need to forge ahead to the last page.

Ty McCormick, senior editor of Foreign Affairs and author of Beyond the Sand and Sea: One Familys Quest for a Country to Call Home

An astonishingly beautiful book. Beautiful in its biting reality. Beautiful in its unearthing of lifes deepest, darkest voids. Beautiful in its depictions of land and cityscapes, great and small. Walking the Bowl is one of the most revealing and heart-rending books I have ever read.

Thomas Lockley, coauthor of African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan

A powerful, beautiful book. Lockhart and Chama throw us into the whirlpool of cruelty, solidarity, triumph and resilient survival of street children in Zambia, Africa, telling the beautiful stories of these kids humanity and forcing us to recognize that most are dying much too soon and too hard.

Philippe Bourgois, author of In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio

Told like a picaresque adventure story, Walking the Bowl captures magnificently the spirit of a hard, hard world. An enviable feat of writing and of sympathy.

Jonny Steinberg, author of A Man of Good Hope

A book about the forgotten of the forgotten. A powerful book. No frills, just hard, spare prose. An intimate account of friendship, betrayal and salvation that requires no atlas to engage and enlighten us.

Wolfgang Bauer, author of Stolen Girls: Survivors of Boko Haram Tell Their Story

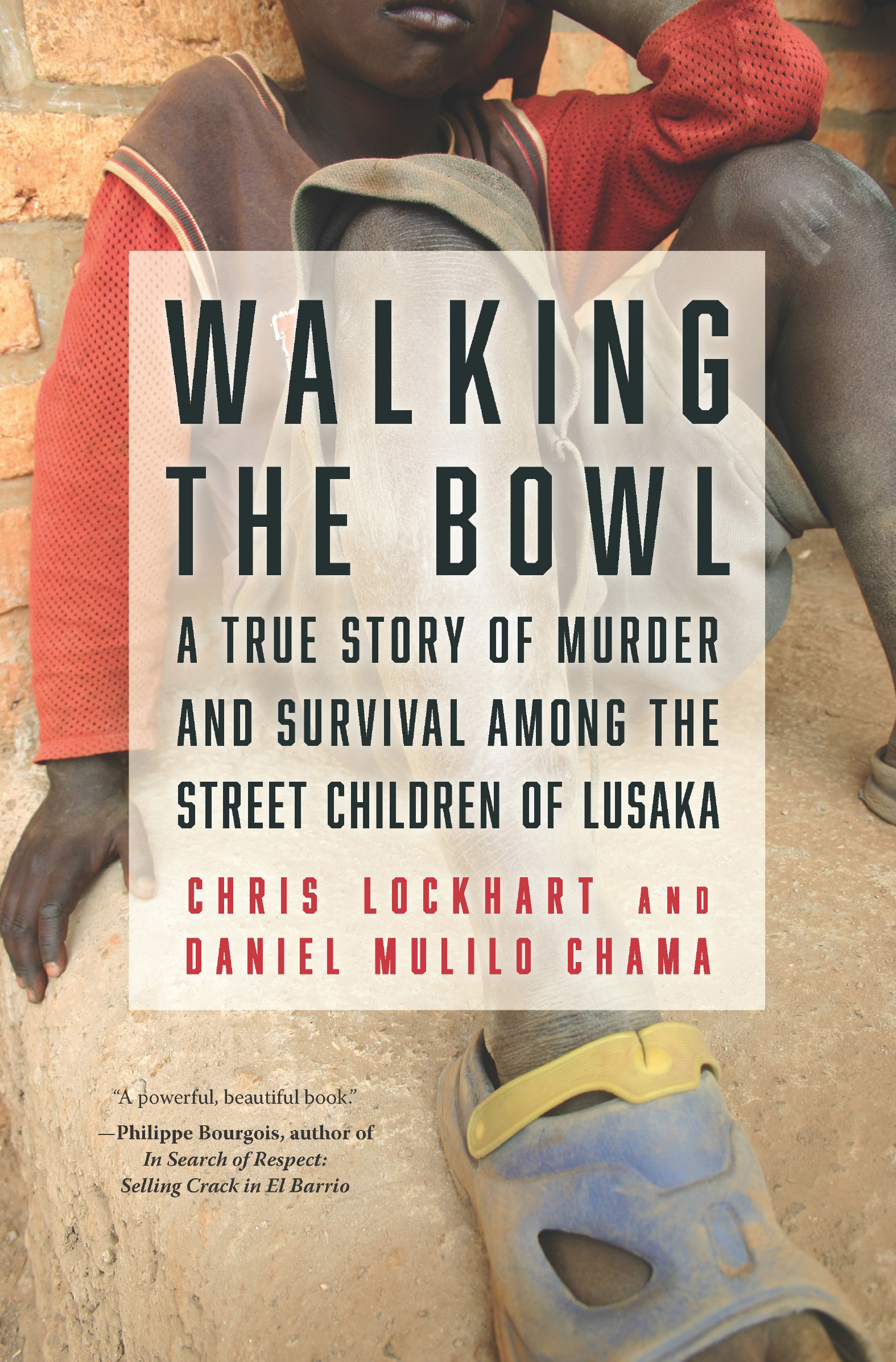

Walking the Bowl

A True Story of Murder and Survival Among the Street Children of Lusaka

Chris Lockhart

and

Daniel Mulilo Chama

Chris Lockhart has a PhD in medical anthropology from the University of California, San Francisco, and UC Berkeley and is the coauthor of Tupa Tjipombos I Am Not Your Slave: A Memoir. He has worked across Africa as an independent researcher and consultant on a variety of development projects in the areas of global health, human rights and journalism.

Daniel Mulilo Chama is a former street child from Lusaka, Zambia. He currently works as an outreach worker for a consortium of nonprofit organizations as he completes his degree in social work at the University of Zambia.

Table of Contents

If you cant pay it back, pay it forward.

Catherine Ryan Hyde

PREFACE

When we started out, our motivation for writing this book was straightforward enough: to call attention to the growing problem of street children around the world. The total number of children who live and survive directly on the streets is widely debated, but estimates range anywhere from the tens of millions to over one hundred and fifty million. These are staggering figures, so much so that it is difficult to wrap ones head around them in any kind of meaningful way. But therein lies the problem: whether intentionally or not, we have become adept at using numbers to mask the true extent and nature of the worst forms of social suffering, thrusting them forth again and again until, like a vaccine, we have become immune to them. Few issues underscore this problem more than street children.

When you read anything on street children, you are likely to walk away feeling a little conflicted, like you just swallowed a gob of information while still knowing exactly nothing about them. More often than not, that information was collected by an army of rapidly trained data collectors who swoop in for a few days armed with checkbox surveys, boilerplate questionnaires, shotgun interview templates and the like. The result is usually a predictable and politically astute report that reduces street children to a bewildering array of typologies (e.g., on the streets, of the streets, part-timers, full-timers, vulnerability stages, resilience stages, etc.), so they can be neatly described and then counted in terms of something akin to a specific unit of activity (e.g., percent who sleep here as opposed to there, percent who survive doing this as opposed to that, percent who have been a victim of this barbarity as opposed to that one, etc.). Working your way through these reports sometimes feels like reading a census takers description of hell.

While there is nothing inherently wrong with this information, there is definitely something missing: the children themselves. In fact, we know very little about their stories, told from their perspective, about their individual lives and experiences. We are just as naive to the everyday realities of their sufferings as we are to their hopes, dreams and desires. So for us, one motivation for writing a book about street children was to write something different, something that moved beyond all the typologies and numbers.

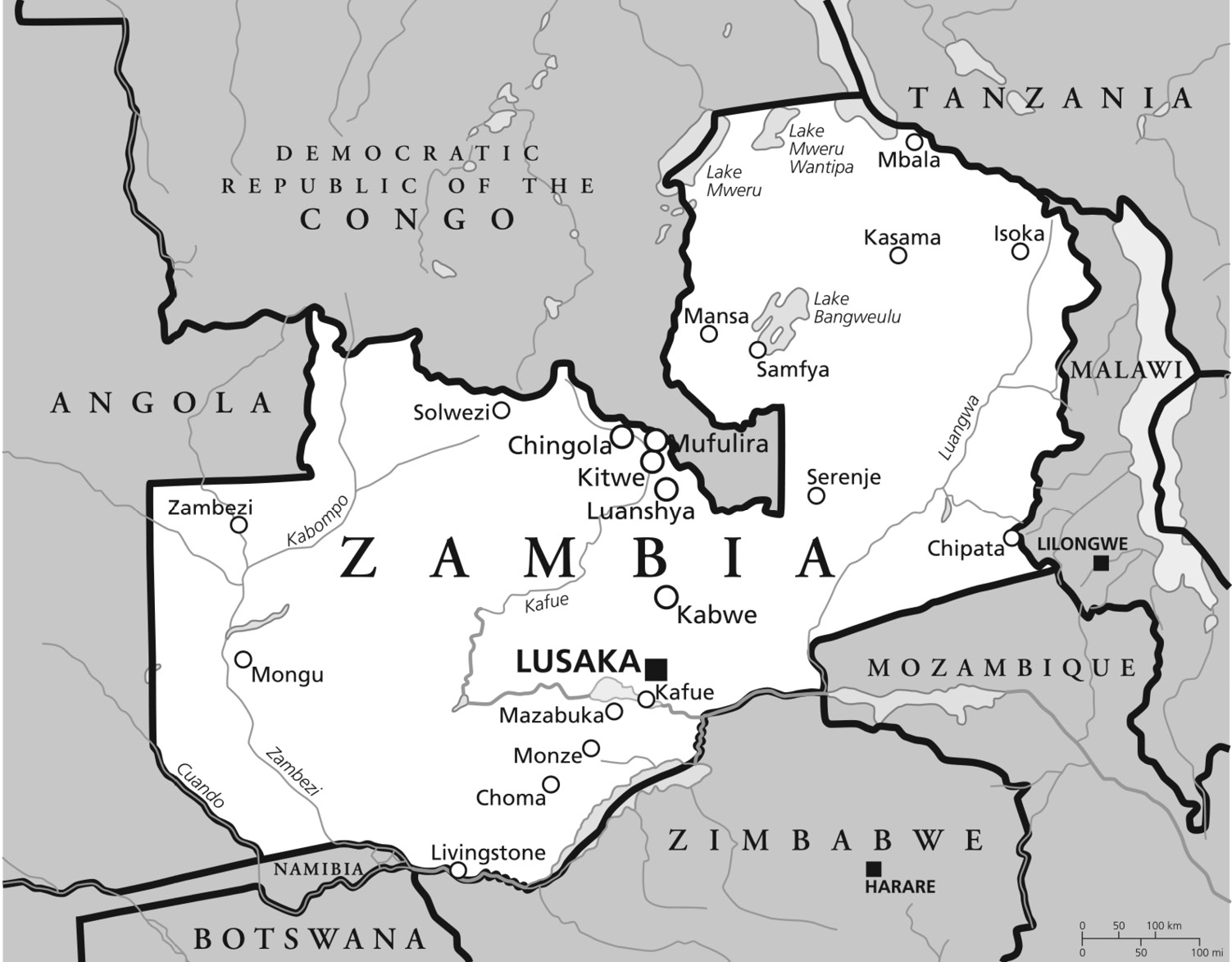

But if we wanted to write about street children differently, we had to approach them differently too. It took a team of eight individuals over five years to do just that, including three years of near total immersion in the street culture of Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia in South-Central Africa. The team consisted of five former street children, a journalism student from the University of Zambia, an outreach worker who was once a street child himself, and an anthropologist. The final two individuals would become the authors of this book and appear in the story itself (Daniel Chama is referred to as the Outreacher and Chris Lockhart as the white man). Space does not allow us to go into all the challenges we faced along the way, but by year three (2016), when most events described in this book occurred, we were able to witness and capture with a digital voice recorder the vast majority of these events. In addition, and whether it was recorded by a team member or not, everything described in this book is the result of hundreds of hours of exhaustive ethnographic interviews, group discussions, impromptu conversations, personal observations and interactions, and everything else that goes into a fully immersive, long-term live and work approach (for a more detailed description on how the book came into being, see the afterword titled About this Book).

But despite all the reasons for writing this book and all the time and preparation it took to immerse ourselves in Lusakas street culture, we could never have anticipated the events that actually occurred. In a lot of ways, it felt like we were pursuing other stories when all along the real one was unfolding right beneath our feet. We missed it because we were so focused on exposing the overwhelming structures and forms of violence that street children have to deal with every day. But that ended up being only half the story. Eventually, we came to understand the other half: how small acts of kindness, passed on to others, can make a difference in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. The children themselves had a lot to do with teaching us this part of the story. They had to show us how small, good things can accumulate and become increasingly powerful and interconnected, like a snowball rolling downhill, smashing everything in its path. That is how we became part of the story toobecause we didnt anticipate any of this until that snowball smashed into us and left us speechless at the wonderment of it all, like children ourselves.

Next page