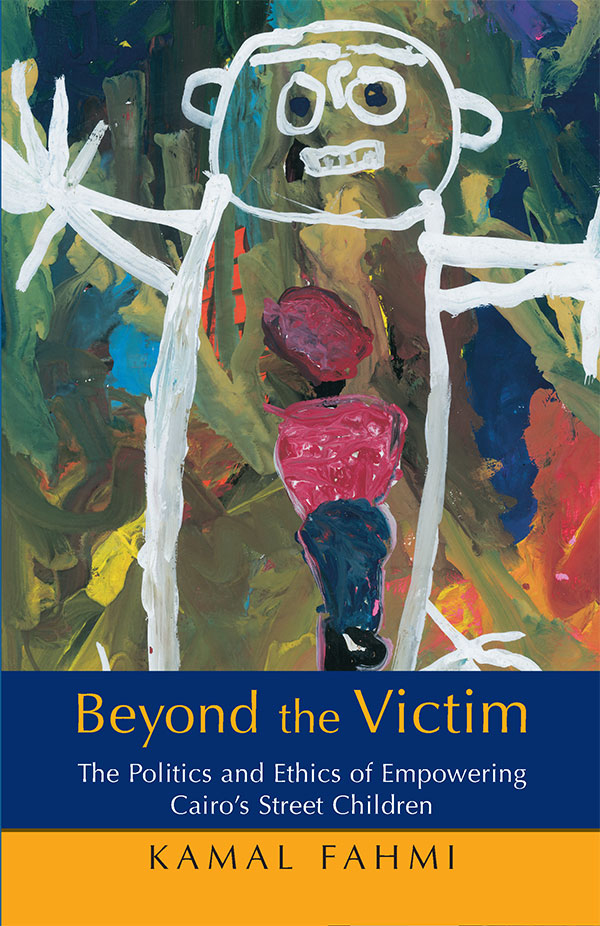

Material in this book is drawn from Kamal Fahmi, Social Work Practice and Research as an Emancipatory Process, in Social Work in a Corporate Era: Practices of Power, eds. Linda Davies and Peter Leonard, Ashgate, 2004. Reproduced by permission.

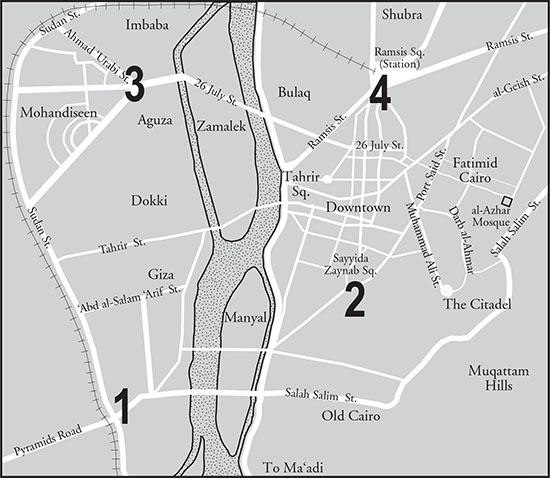

Map on page xiv by Ola Seif.

Copyright 2007, 2014 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018

www.aucpress.com

First published in hardback in 2007

This electronic edition published in 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 063 9

eISBN 978 161 797 563 9

Version 1

For my parents

Practice that is about genuine empowerment can never be certain of where it is heading, butcontrary to the views of some post-modernistsit can, and indeed must, proceed in a way that takes account of universal value, moral and ethical principles, even if the way in which these are defined and operationalised will vary over time and across cultural settings.

(J. Ife 1999, 222)

Contents

Part 1

Theoretical and Methodological Framework

Part 2

The Story

T his book is the outcome of many years of fieldwork and research aimed at developing an understanding of the lived experiences of some of the youngsters called and labeled street children. My deepest gratitude and respect go to all those boys and girls, and young men and women who allowed me and my team of street workers and researchers into the habitat they have made of the street in an attempt to resist exclusion and chronic repression and to affirm their human agency. From these youngsters I learned a great deal about myself and about the social realities that encourage them to continue to struggle to survive in circumstances that most of us would find, at the very least, unbearable.

I am forever indebted to Linda Davies from McGill University for her enthusiastic and committed encouragement, support, and guidance during the preparation of the original manuscript.

I would like to express my sincere appreciation and gratitude to my friend and colleague Jacques Pector for the inspiring and enlightening dialogues we had and for his help in identifying appropriate documentation regarding many of the themes discussed in this book.

To the team of street workers and researchers who participated in the different phases of the participatory action research reported in this book, I am deeply grateful for their commitment, hard work, and love.

Finally, I am very lucky to have family and friends who have encouraged and supported me throughout the years that culminated in the writing of this book.

| AR | Action Research |

| lATTrueQ | Association des Travailleurs et Travailleuses de Rue du Qubec |

| BCJ | Bureau de Consultation Jeunesse |

| CAPMAS | Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics |

| CIDA | Canadian International Development Agency |

| EAD | Egyptian Association for Development |

| EASSC | Egyptian Association to Support Street Children |

| EC | European Community |

| ILO | International Labor Organization |

| MISA | Ministry of Insurance & Social Affairs NCCM National Council for Childhood and Motherhood |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| PAR | Participatory Action Research |

| PIaMP | Project dIntervention auprs des Mineur(e)s Prostitu(e)s |

| PO | Participant Observation |

| PR | Participative Research |

| SDC | Social Development Consultants |

| UNICEF | The United Nations Childrens Fund |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

Greater Cairo: numbers indicate nones of street work.

D espite widespread concerns and numerous intervention programs aiming at its eradication, the street children phenomenon continues to escalate throughout the world. Indeed, the resilience of the phenomenon matches, if not surpasses, that of the children themselves. I believe that the failure to adequately address this complex and very diverse phenomenon is the result of conceptual confusion with respect to defining who a street child is. The dominant discourse on street children obstinately defines them as victims or deviants to be rescued and rehabilitated. As such, the capacity of many of these children for human agency is occluded by excluding them from participation in the construction of solutions to their problems. I argue that far from being mere victims and deviants, these children, in running away from alienating structures and finding relative freedom in the street, often become autonomous and are capable of actively defining their situations in their own terms. They are able to challenge the roles assigned to children, make judgments, and develop a network of niches in the heart of the metropolis in order to resist exclusion and chronic repression. I further argue that for research and action with street children to be emancipatory, it is necessary to acknowledge and respect the human agency the children display in changing their own lives and to capitalize on their voluntary participation in non-formal educational activities, as well as in collective advocacy.

My arguments are based on fieldwork undertaken with Cairene street children and youth over a period of eight consecutive years (19932001), which I reflectively narrate and report in this book. One major objective is to demonstrate how this fieldwork was implemented through the articulation of a participatory action research (PAR) methodology of social development practice and research that eclectically combined street ethnography, street work, and action science. In my view this combination is particularly pertinent for PAR undertakings that target excluded populations.

Over a period of more than ten years prior to beginning fieldwork in 1993, I had incorporated a PAR framework into my professional work in the youth sector, in both Montreal and Cairo. Indeed, an abiding interest in praxis, that is, making research an integral part of practice, has been a major professional concern on my part since the late 1970s, when I first started my career in social work, and in subsequent international development activities. I have experimented with methodologies drawn for the most part from the Southern (Freirean) PAR tradition (see ), which conceives PAR as basically a grassroots practice methodology with a built-in mechanism of ongoing reflection and dialogue that serves to enlighten action, empower participants, tackle contradictions, and generate experiential knowledge.