Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

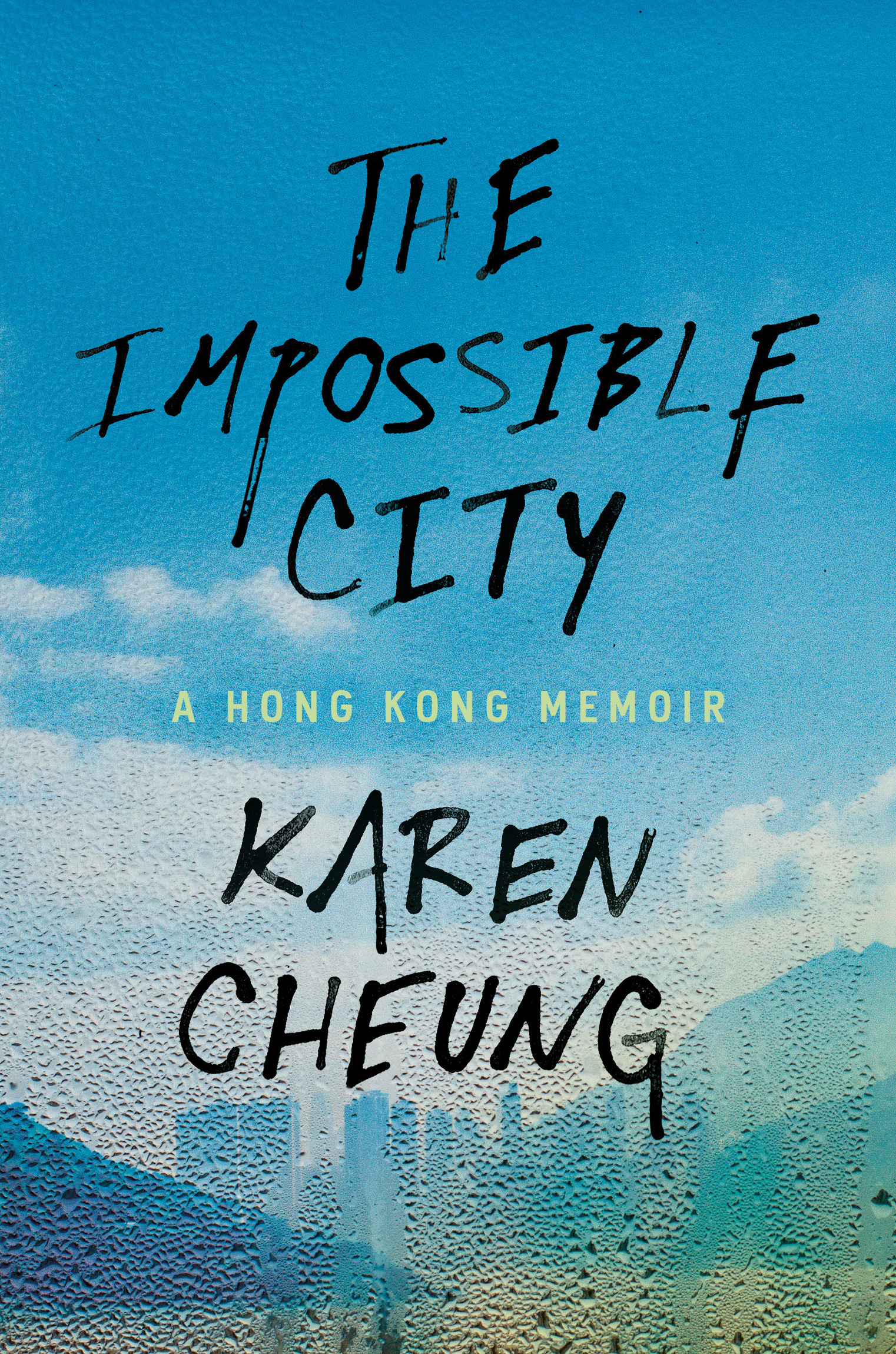

The Impossible City is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2022 by Karen Cheung

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cheung, Karen, author.

Title: The impossible city : a Hong Kong memoir / Karen Cheung.

Other titles: Hong Kong memoir

Description: New York : Random House, [2022]

Identifiers: LCCN 2021027512 (print) | LCCN 2021027513 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593241431 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593241455 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cheung, Karen. | Hong Kong (China)Social life and customs21st century. | Hong Kong (China)Social conditions21st century. | Hong Kong (China)History21st century. | Hong Kong (China)Biography.

Classification: LCC DS796.H753 C44 2022 (print) | LCC DS796.H753 (ebook) | DDC 951.2506/12092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021027512

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021027513

Ebook ISBN9780593241455

randomhousebooks.com

Cover design: Rachel Ake

Cover images: Shutterstock (condensation), Stocksy (Hong Kong)

ep_prh_6.0_139149577_c0_r0

Contents

Preface

If you had asked me when I was eighteen what I thought of Hong Kong, I would have told you that I was ambivalent. Hong Kong was a place in which I just happened to find myself. The chaotic streets where dripping water from air conditioners was always sliding down my hair; the thick summer air steeped with the scent of fried peppers stuffed with fish paste; the view of the fabled harbor where a mountain ridge peeks out behind jagged buildingsthis was merely the setting for the messy childhood I was trying to navigate and survive. I was shuttled between separated parents in two different cities, between a private school and a conservative public school, between my fathers good mood and his explosive temper. I had no identity yetI was not an immigrant or a third-culture kid or even a Hong Konger.

I was not a Hong Konger because I did not yet know what that meant. I was born in Shenzhen, a neighboring Chinese city where my parents met, and arrived in Hong Kong before I turned one. My fathers side of the family moved to Hong Kong from Hoiping in China in the 1950s, and my grandmother brought with her pagan superstitions and archaic village phrases. My mother is from Wuhan and to this day she cannot speak my mother tongueCantonese, the southern Chinese language spoken in Guangdong Province and Hong Kongwithout an accent, swerving back to Mandarin after a few sentences. My Singapore-raised brother and I conversed in English. But my family never thought of this as an emigration story; Ive never even heard anyone refer to themselves as a Hong Konger. It did not seem important, then, to give a name or a narrative to what we were.

When I was four, my small city went from being a British colony to Chinese property. At the time of the historic event, known as the handover, literature and media depicted Hong Kong as at the intersection of clashing identities, but the truth was worse: We had no identity. The only thing that could be called a Hong Kong identity was the fact that we had some neat colonial buildings but also bamboo scaffolding and great Chinese food in our dai pai dongs. We defined ourselves in negativesnot Communist, no longer colonial subjects. The fact that we had rule of law, which exists in a great many other countries, became the basis for an entire collective identity. It would take a few decades of experimentation before each of us would come to define this identity for ourselves.

My childhood was set in an old, sluggish neighborhood in To Kwa Wan, Kowloon, near a decommissioned airport and a walled city turned park. Dark gaming arcades frequented by truant kids were juxtaposed with restaurants that served steaks seasoned with too much tenderizer; the cluttered faades of public housing stood next to glossy private apartment blocks with their own clubhouses and pools. Across from stores run by ethnic-minority families, theater companies put on plays in a former cattle slaughterhouse. When the typhoons hit in the summer, wed tape huge crosses on our windows to keep them from shattering; when a plane flew overhead, wed stick fingers in our ears. This was my kingdom. I did not understand any of the evening news on every night at dinner, nor did I venture out much to Hong Kong Island or the New Territories. I stayed mostly in libraries, cramming myself with English literature and Chinese history, so I could score well enough to earn a coveted university place in Hong Kong. I lived inside television shows, books, and, later, the internet.

When I was sixteen, I had a sort-of crush on a boy from a different school, sort-of because it wasnt so much that I wanted to date him as that I wanted to be him. We never met, but he blogged about Jim Jarmusch, Frank Sinatra, and tattoo parlors. He was what I thought then to be the epitome of cool. He later went on to film school in London. I read his blog religiously because I was so bored with my life in Hong Kong. I daydreamed about going to gigs, seeing art house cinema, having intellectually stimulating conversations, and being in the midst of the next great literary movement. I could not find any of this at home. My classmates and I were brought up on the belief that nothing was more important than securing a job that would eventually buy us a flat, a basic human right that had become nearly impossible for my generation, and these jobs were usually soul sucking. Hong Kongs brand of capitalism makes it easy to live in a place and never engage with it.

I thought that when I eventually became an adult I would be one of those people who power-walked in heels across the bridge of the International Finance Centre in the central business district. The building is an altar of marbled floors, luxury shops, and office workers in Brooks Brothers tiesa sleek, phallic tower that thrusts into the thick mist guarding the night sky. My father told me that it was normal we did not know our neighbors, because no one knows their neighbors. I had bought into all the clichs that the adults told me about my city: that it was an apolitical cultural desert inhabited by go-getters who have no real values except becoming rich. But I did not know yet that this is a place where parallel universes coexist, and you could live your entire life here without ever pulling back the curtains on the other Hong Kongs.

Hong Kong is a subtropical city with over seven million people, an oft-quoted factoid that previously existed in my head in abstraction. I understood what that meant only when I left the city for the first time, on an exchange semester in Glasgow. On the main street of the Glasgow city center on a Saturday, I almost had a panic attack. Where are all the people? There was less than a tenth of the crowd I would see back home. Hong Kong pulses with a sort of frenzied energy, and speaks the language of alienation and impatience. Its difficult to walk on the street, any street, in Hong Kong Island and Kowloon without accidentally touching someone. My favorite sign in the city is located at the airport, next to the platform for inter-terminal trains: Relax, train comes every two minutes. In public parks there are boards that list activities you are not allowed to partake in: