Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

WALKING PEPYSS LONDON

About the Author

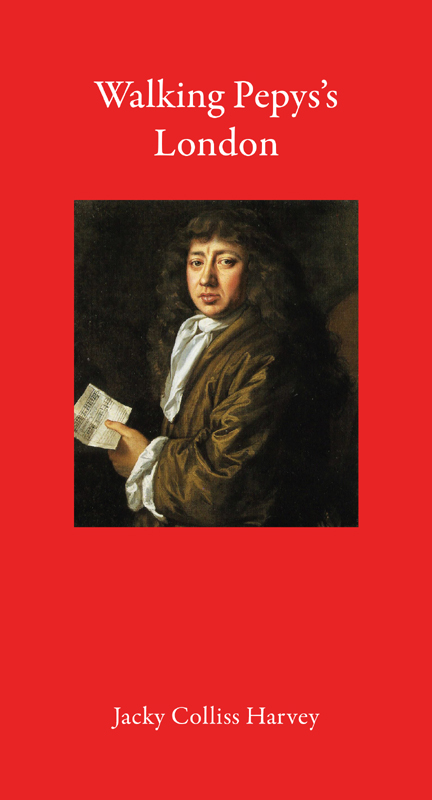

Jacky Colliss Harvey worked in museum publishing for many years and as a writer and commentator on the arts and their relationship to popular culture. She is the author of the New York Times bestseller RED: A History of the Redhead and The Animals Companion: People and their Pets, a 26,000-Year-Old Love Story. A country mouse by birth, she has been fascinated by London and its multifarious history since first arriving in the city as a student.

Walking Pepyss London

Jacky Colliss Harvey

Published in Great Britain in 2021 by

The Armchair Traveller (an imprint of Haus Publishing Ltd)

4 Cinnamon Row, London SW11 3TW

www.hauspublishing.com

@HausPublishing

Copyright 2021 Jacky Colliss Harvey

Cartography produced by ML Design

Maps contain OS data Crown Copyright and database right (2020)

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-1-913368-28-9

eISBN: 978-1-913368-29-6

Typeset in Garamond by MacGuru Ltd

Printed in Czech Republic

This one is for my Twin, with love and gratitude.

TOther Twin

Introduction

S AMUEL PEPYS, walker, accidental historian, and creator of the most celebrated diary in English literature, was born in a house at the Fleet Street end of Salisbury Court, London, EC4Y 8AA on 23 February 1633 making him, for those with an interest in such matters, a Pisces and his celestial ruler Neptune.

Salisbury Court (now complete with a blue plaque to commemorate its most famous son) is an alleyway that runs pretty much straight north to south; its other end, in Pepyss day, dipped down into the Thames at the landing stage of Dorset Stairs. The area took its name from Salisbury House, a hostelry of the grandest sort, built on land originally owned by the Bishop of Salisbury and notable for lodging, among others, Prince Arthur in 1498. By Pepyss time, Salisbury House had become Dorset House, the London seat of the Sackvilles. From 1629, Salisbury Court was also home to Salisbury Court Theatre. You might say that Pepys, the archetypal Londoner, was from his first breath encircled by all the elements social, cultural, architectural and topographical that formed the city that was to make his fortune and his name; and, as the future Chief Secretary to the Admiralty, that he had a goodly splash of aquatic pre-destination thrown in.

The aim of this book is to acquaint the reader with London as it was lived in Pepyss day from the pavement up, and as her streets were experienced by Pepys himself. Pepys was a prodigious walker. The two-and-a-half miles to Whitehall from his house in Seething Lane were accomplished on an almost daily basis, and so many of his professional conversations took place while walking with a confidante or patron that the streets became for him an alternative to his office. But Pepys didnt only walk his city, he observed it: its daily face, its other inhabitants, the systems that kept it functioning, the new powers within it replacing the old. And his recording of these observations in his famous diary not only gives us an unparalleled means of time-travelling back more than 350 years but also makes Pepys a sort of seventeenth-century London version of the celebrated nineteenth-century Parisian flneur: the passionate observer, one whose greatest enjoyment was to establish his dwelling in the throng, in the ebb and flow, the bustle, the man for whom, as Baudelaire put it, The crowd is his domain. Pepys walked because he liked to walk. Young Michell [the son of one of Sams regular booksellers] and I, it being an excellent frosty day to walk, did walk out, he writes on 6 January 1667,

he showing me the bakers house in Pudding Lane, where the late great fire begun; and thence all along Thames Street, where I did view several places, and so up by London Wall, by Blackfriars, to Ludgate; and thence to Bridewell, which I find to have been heretofore an extraordinary good house, and a fine coming to it, before the house by the bridge was built; and so to look about

What better guide to walking London could there be?

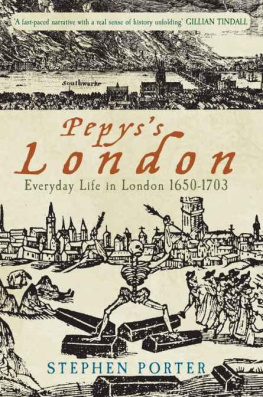

Today, however, along with comfortable shoes and an ear cocked for an approaching double-decker bus, those seeking to explore Pepyss London also need an active imagination. London has suffered two extinction-level events in her recent history. The first, the Great Fire of 1666, was witnessed by Pepys; the second, the Blitz of the Second World War, destroyed most of the sights and buildings in the old City that had somehow survived the first. Most, but not all: there are still rare survivors, which feature as stopping points on the five walks that form the body of this book; others can be imaginatively recreated, if the walkers of today are willing to pause and to abstract themselves from the tumult of the twenty-first century and perhaps (ever mindful of that pestilential traffic) to half-close an eye. Londons historical blueprint is remarkably persistent, as if the older the stamp put upon her hills and fields and the banks of her river, the more stubbornly it remains. After the Fire of 1666, Londoners simply rebuilt on the same plots and to the same shapes the properties they had lost; and despite even the Blitz, there remains within the old City (which for our purposes we take as stretching roughly from Fleet Street to the Tower) the original pattern of many of her most significant streets and of her tiny linking alleyways and courts, such as the one where Pepys was born.

The same is true of Whitehall and Westminster, to a lesser extent, and along the banks of the Thames itself, while in Greenwich and Deptford, where Pepys Clerk of the Acts to the Navy Board from July 1660 strolled and bustled and occasionally plotted, there are still buildings and vistas that can bring seventeenth-century London vividly to life.

Even when the buildings and street plans are lost, the ghosts remain. When I bought my twenty-first-century flat on the Isle of Dogs (the peculiar teardrop of land that hangs down into the Thames like a uvula), I had to take out chancel insurance, as somewhere under the basement car park of my building lies the footprint of a church. An oil painting now in the Museum of London Docklands and dating from about 1620 shows the Isle of Dogs as Pepys must have seen it many a time from Greenwich: the flat fields, the shimmer of marsh, the sails of a windmill. And sure enough, top right, as the Thames makes its final swing eastward, there is a jumble of small buildings, like flotsam deposited at the rivers bend, and among them, a church steeple.

*

To us, the London of Pepyss time would seem miniscule. From east to west, within its medieval and in some places Roman walls (still standing, here and there, in Pepyss day), the City proper measured a little under fivekilometres or three miles across. Walk from Fleet Street down the Strand and enough of a gap would open before you for Westminster and Whitehall to count as a separate place. Covent Garden was a garden; Lincolns Inn Fields was fields, Smithfields the same. The so-called Faithorne and Newcourt map of 1658 perfectly if unknowingly timed to record London just before the Fire shows one single street of houses north of Holborn and open countryside beyond. (Pepys knew William Faithorne, the maps engraver; one wonders if he owned a copy.) Ribbon development runs along Fenchurch Street out to a dinky little windmill. St Jamess Palace, today between Piccadilly and Pall Mall, sits in open space, with deer tossing their antlers before it. Looking behind you from St Jamess, the jumble of roofs of the City would still have been low-rise enough to echo in their lines the rise and fall of the land beneath. Those on Ludgate Hill stood higher, for example; St Pauls higher than everything else. Maybe half a million people would have answered London if in 1660 you had asked them where was home. Greater London today is forty-five miles or over seventy kilometres across, from Havering in the east to Hillingdon in the west, and its population sits at just over eight million and counting.