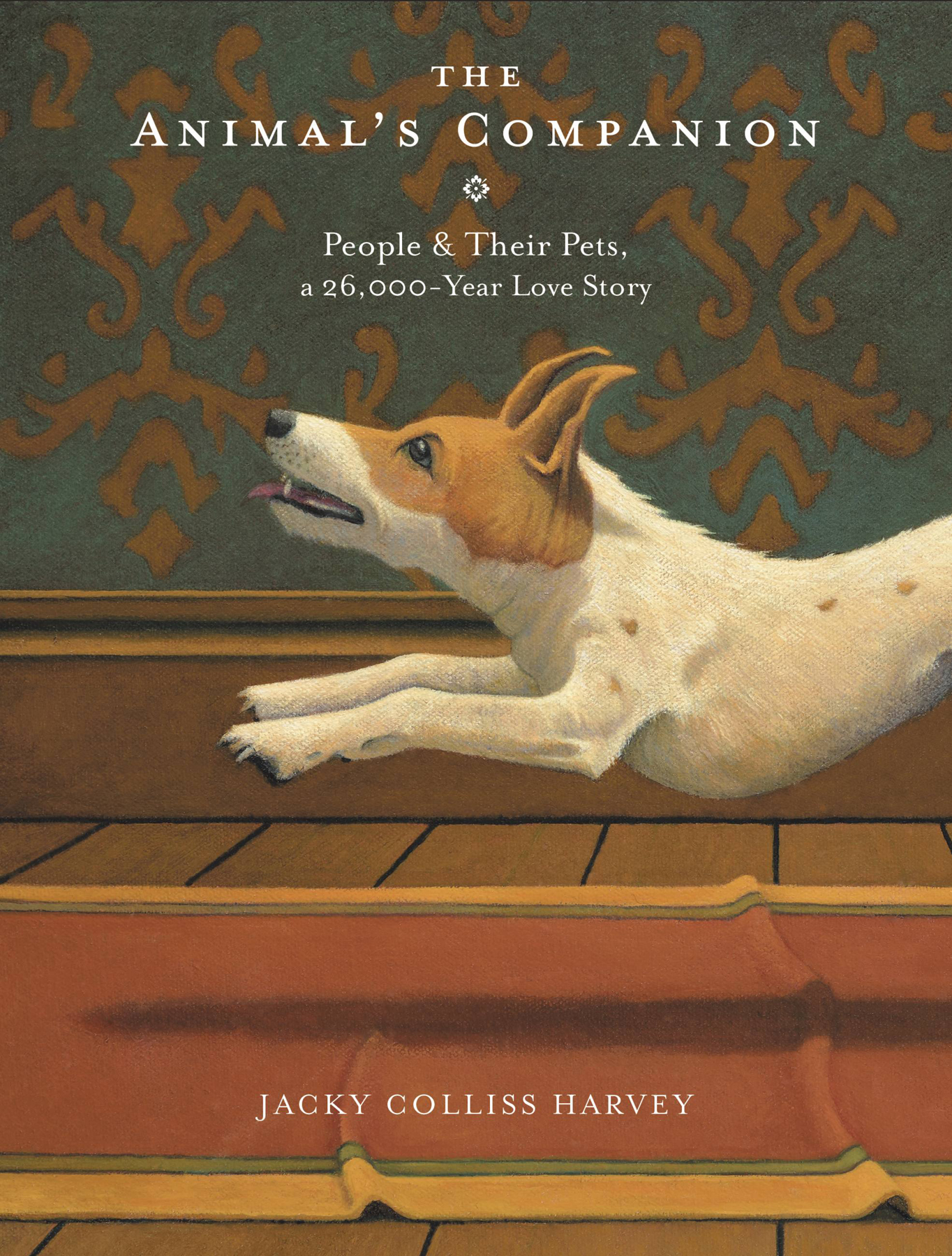

My mother, me at age 3, and my cat Freddy, also age 3, in our garden in Suffolk.

In evolutionary terms, pet ownership poses a problem

John Archer, Why Do People Love Their Pets, 1997

A few years ago I wrote a book on the history of the redhead, as part of which I found myself in the Dutch town of Breda, at the largest gathering of redheads on the planet. And there I met Daniel and Joeredheads the pair of them, and not only that but dressed to match as well: identical yellow bandanas round their necks and matching sunglasses. And we got talkingor rather I, in that entitled way that writers have, began asking questions, and Daniel did his best to answer them. Were he and Joe always dressed alike? I asked. How long had they been in each others lives? How did people react when they saw the two of them together? And given that what I saw was a settled adult pair, wholly at ease with each other and praiseworthily forbearing when it came to me, and that life for young redheads, especially young male redheads, can sometimes be a tad taxing, let us say, how had life been before they had each other, when they were younger and on their own? At which Daniel began describing the usual experiences of soft discrimination and of being marginalized at school, and Joe gave a wide, luxurious, and noisy yawn, settled his head on his paws, and went to sleep. Smiling, Daniel explained, Hes heard all this before, and reached out and patted Joes head. And looking at the two of them, I found myself begin one of those idle inner pondersin this case why, for millennia, as members of the dominant species on this planet, we have been so impelled to take members of other species into our homes and lives and (hopefully) cherish and indulge and care for them as if they are the exact thing they so unalterably are notlike us.

Beware those idle inner question marks. They start out as such unassuming little sprouts, and just what social media was made for. Why do we have the pets we have, I asked, and within hours my readers were sharing with me the pictures and the stories of every beloved pet you can imagine, from ginger cats and dogs to strawberry-roan horses and ponies, from auburn guinea pigs and hamsters to a tiny Rhode Island Red chick and even a henna-colored bearded lizard. And that momentary ponder with Daniel and Joe has become what this book is about. Or to be specific, Daniel, and all the other Daniels there have been down the ages, has become what this book is about. Because this book is an exploration of the history not of the pet (the handsome red setter) but of the pet owner.

I come from a family of animal lovers within a nation, so we are told, of animal lovers; much as that description would for centuries have In effect, this book is an unpacking of a similar drawer of my own. Perhaps, with a subject as diverse and wide-ranging as this one has proved to be, it was after all a valid way to set about it.

Most significantly, all the way through my childhood and my growing there were animals. The first that was truly mine was also ginger, a swaggering tomcat named Freddy, who had paws the size of my infant hands, a purr you could feel through the floor, and fur as perfectly marked as red onyx, and who is still, four decades after his death, there in the measure of all other cats for me. But there were also bantam chickens, deep-bosomed and high-sterned as tiny Tudor galleons, sallying forth across the lawn like a miniature feathered armada; guinea pigs with their squeaky Morse code of wheek-wheek-wheeeek; and two rabbits, one an albino and one as elegantly black-and-white as a two-tone brogue. There were temporary pets in the form of half-mangled fledglings and field mice still wet with cat drool; there were baffling pets in the form of silkworms, stick insects, and goldfish, and, at the other end of the scale entirely, an Irish wolfhound. My mother told me stories from her childhood of her animals, and on those joyfully grubby student train journeys across Europe, I in turn swapped tales with my girlfriends of the animals from their childhoods.

It was only as I began working on this book, and listening in that awakened, note-taking way, that I realized quite how frequently we animals companions tell such tales. People would ask me what I was working on, and half an hour later the stories of them and their animals would still be flowing. Nor had I truly reflected on how profoundly such stories connect us, even between generations who never met. Both my grandfathers died long before I was born, but now I know that my mothers father, a sandy-haired man-mountain who went through the North Sea convoys of the First World War as a teenage sailor, and who was hard enough when fire-watching in the Second to pull out the severed tendons in his own forearm after he was hit by shrapnel, was also fond and daft enough where the household hens were concerned to walk around the garden summoning them by calling, Come along, ladies! Animals bond usus to them and we to one another. If we are pet owners, that is true to the power of ten.

As I look back, all the most important lessons of my life were taught to me by animals: the realities of love and loss and the impenetrability of death, which could take a warm, breathing, living flank and overnight turn it into something lifeless, cold, and solid; the imperatives of sex; the largeness of care and of responsibility. The effortless teaching of these lessons was, I am sure, why my parents believed that to have pets was a good, indeed essential, part of any childhood, expanding the imagination and sharpening empathy, even if the precepts I drew from these experiences were not always those my parents had anticipated. Growing up with animals rounds out your understanding of the world. I had a glorious shimmering firebird of a cockerel who began building nests; while one of my rabbits, the black-and-white one, turned out to have a heart condition and every morning, after his daily digitalis tablet, which did indeed come in the form of a little blue pill and was served to him cunningly crushed up in warm milk, would leap aboard his guinea pig brother hutchmate. Animals are better educators, where sex is concerned, than any book. Growing up a redhead made me bold; but it was growing up with animals that made a liberal out of me.