RED

A History of the Redhead

JACKY COLLISS HARVEY

This one is for Mark.

CONTENTS

The Redhead Map of Europe.

There is a good deal of controversy over the accuracy of such maps, as there is indeed over so many issues associated with red hair, but what it shows very clearly is the hotspot in Russia of the Udmurt population on the River Volga and the increasing frequency of red hair the farther north and west you go, whether in Scandinavia, Iceland, the British Isles, or Ireland.

Fig. 1: This portrait of a redheaded Afghan girl was taken in 2004 by REZA in the Pashtun tribal zone in Afghanistan.

Fig. 2: Uyghur girl photographed in Kashgar, in Chinas Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The ethnicity of the Uyghur is Turkic, rather than Han Chinese. They see themselves as an occupied people, and identify both ethnically and culturally with the non-Chinese civilization of the Tarim mummies rather than with that of Bejing, referring to their region as East Turkestan. Recently there has been ethnic violence in the region, bombings and knife attacks, indiscriminate as these events always are in the victims they have claimed.

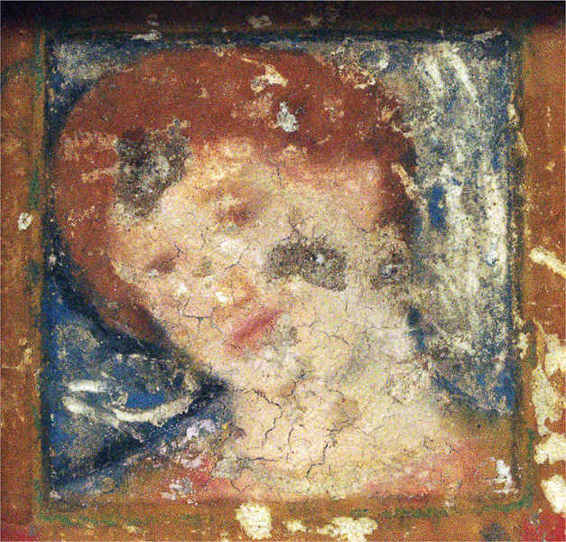

Fig. 4: The red-haired divinity from coffer 32 in the ceiling of the Ostrusha tomb in central Bulgaria. Dating back to 330310 BC, it is one of the earliest representations of a redhead in Western art.

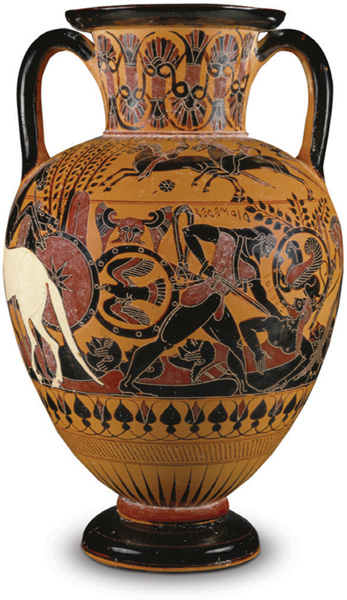

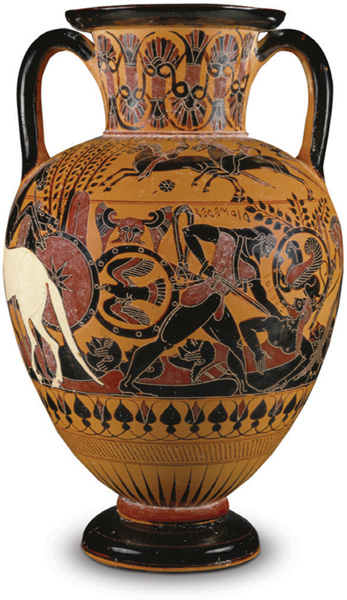

Fig. 5: King Rhesos and a very rude awakening. This Chalkidian black-figure amphora was made in southern Italy about 540 BC. The artist, known to us as the Inscription Painter, uses a red glaze for Rhesoss hair and beard. As the story was recounted in Homers Iliad, Odysseus and Diomedes infiltrated the Thracian camp outside the walls of Troy, hoping to steal their fine horses, one of which can be seen being led away to the left.

Fig. 6: This tiny terracotta figure, just 13 centimeters high, of an actor playing the part of a runaway slave, was made in Athens between 350 and 325 BC. It came to the British Museum from the collection of Eugene Piot (181290). Piot squandered a fortune collecting treasures from across the Classical world. Microscopic remains of red paint still adhere to the figures terracotta hair.

Fig. 7: Gabriel Angler the Elder, The Agony in the Garden, 144445, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. The altarpiece this panel comes from was made for Tegernsee Abbey in Bavaria, where, four centuries before, in the eleventh century, an unknown monk wrote the Ruodlieb, one of the earliest knightly epics, containing one of the first warnings against men with red hair: A red beard rarely hides a good nature.

Fig. 8: Antonello da Messina, Calvary, 1475. The well-tended landscape, the figures of the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, even the central figure of Christ on the Cross seem oblivious of the agonies going on around them to left and right. Note, however, the point being made by the artist in showing the impenitent thiefs red hair. Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp.

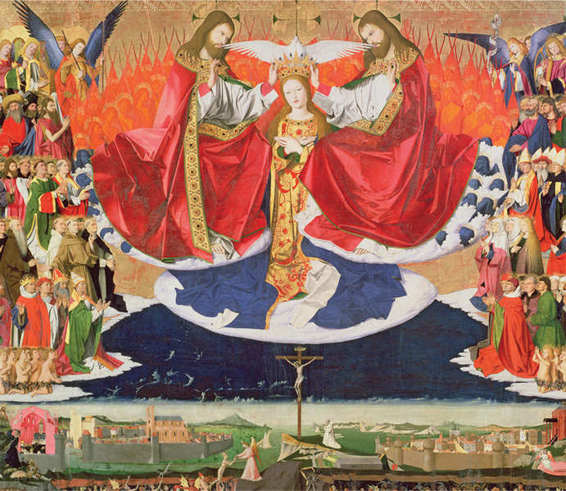

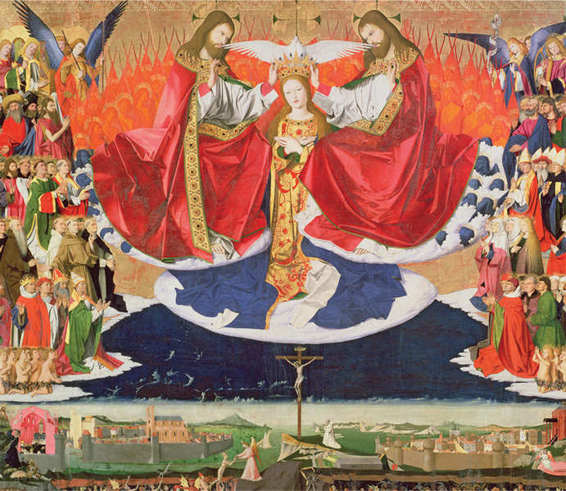

Fig. 9: Enguerrand Quarton, The Coronation of the Virgin, 1454, Monastery of Chartreuse du Val de Bndiction, Villeneuve-ls-Avignon. The Carthusian order is closed and silent, with monks undertaking a life of prayer and contemplation, each within his own cell. Each cell, however, has a garden, and once a week the community walks in the countryside. An atmosphere of calm and quiet, and of love of the world while being removed from it, permeates Quartons painting.

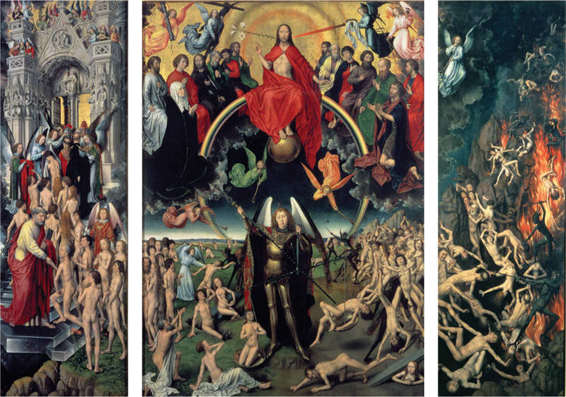

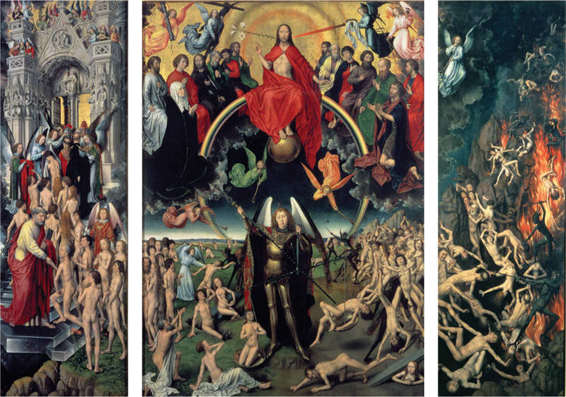

Fig. 10: Hans Memlings triptych of The Last Judgement, c.1467-73. Memling was around forty years old when he painted this work. Born in Germany, he lived in Brussels and Bruges, and his paintings, which represent one of the summits of Early Netherlandish art, feature redheaded Virgins as well as angels and here, two souls of the saved, walking up the crystal stairs to Paradise.

Fig. 11: Studio of Martin Schongauer, Noli Me Tangere, c. 1480. Schongauer, like Memling, was a follower of Rogier van der Weyden. His works, like Memlings, are prized for their use of color and the quality of their execution. And like Memling, Schongauer created redheaded Virgins, saints, and angels, as well as Magdalenes.

Fig. 12: Jan van Eyck, The Crucifixion, c. 143540. This painting is twinned with a right-hand panel showing the Last Judgment. It is the Crucifixion as narrative, and has been aptly called almost an eyewitness account. The Virgin is almost indistinguishable, shrouded in her blue robes as if these are her grief; Mary Magdalene, identifiable by her red hair, lifts up her hands in a gesture that combines horror, pity, and entreaty all at once.

Fig. 13: Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Mary Magdalene in the Cave, 1876. Now in the Hermitage, this work is typical of the highly finished Salon style of paintingso establishment on the surface, and at the same time so ripe for decoding and reinterpretation.

Fig. 16: Elizabeth I, painted by an unknown artist around 1575. Now in the National Portrait Gallery, London, this portrait epitomizes both Elizabeths image and her elegance. The choice of colors in her dress and her accessories is perfect for a redhead, the masklike face somehow both ineffably sad and totally remote.