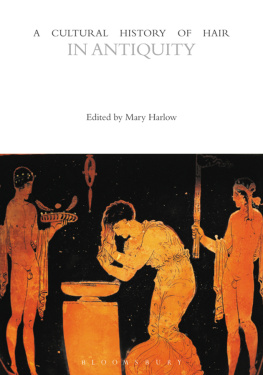

A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

VOLUME 1

A Cultural History of Hair

General Editor: Geraldine Biddle-Perry

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Hair in the Middle Ages

Edited by Roberta Milliken

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Hair in the Renaissance

Edited by Edith Snook

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Margaret K. Powell and Joseph Roach

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Empire

Edited by Sarah Heaton

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Hair in the Modern Age

Edited by Geraldine Biddle-Perry

A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

IN ANTIQUITY

VOLUME 1

Edited by Mary Harlow

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

A Cultural History of Hair offers an unparalleled examination of the most malleable part of the human body. This fascinating set explores hairs intrinsic relationship to the construction and organization of diverse social bodies and strategies of identification throughout history. The six illustrated volumes, edited by leading specialists in the field, evidence the significance of human hair on the head and face and its styling, dressing, and management across the following historical periods: antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Empire, and the Modern Age.

Using an innovative range of historical and theoretical sources, each volume is organized around the same key themes: religion and ritualized belief, self and societal identification, fashion and adornment, production and practice, health and hygiene, gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, class and social status, representation. The aim is to offer readers a comprehensive account of human hair-related beliefs and practices in any given period and through time. It is not an encyclopedia. A Cultural History of Hair is an interdisciplinary collection of complex ideas and debates brought together in the work of an international range of scholars.

Geraldine Biddle-Perry

MARY HARLOW

In the later fourth or early fifth century CE, a neo-Platonist philosopher, warrior lord and reluctant bishop, Synesius of Cyrene, wrote a treatise on baldness. This work both praised and parodied an earlier Encomium on Hair by the firstsecond century orator, Dio Chrysostom. Synesius treatise typifies the writing of the educated elite of his time. Despite ostensibly being part of a Christian world, Synesius expressed his eruditeness by an extensive knowledge of the traditional pagan classics. On Baldness expresses many of the commonly held opinions of hair and multiplicity of meanings associated with it in antiquity. Synesius began his defense of baldness when he was wounded to the heart when the terrible thing happened and my hair began to fall off

Synesius response to Dios encomium is as playful as it is learned and literate. He openly acknowledges the rhetorical games that both Dio and he use to manipulate audience reactions to their speeches. He begins by comparing hairy animals to bald intelligent ones:

And just as man is the most intelligent, and at the same time the least hairy of earthly beings, conversely it is admitted that of all domestic animals, the sheep is the stupidest, and this is why he puts forth his hair with no discrimination, but thickly bundled together. It would seem that there is a strife going on between hair and brains, for in no one body do they exist at the same time.

Having stressed intelligence, the treatise then begins a catalogue of positive attributes of baldness. Listing Diogenes, Socrates, and Silenus, he argues that all philosophers, the wisest of men, are bald, indeed if a man is not bald he is unlikely to be wise. The divine elements of nature that are revealed to man are spheres which are bald and while simpler souls may dwell in a hairy head, a wise soul will find a sphere, a bald head, in which to live.

Synesius knows that cultural practice and custom can influence how men wear their hair, and that the rules are different for women:

always and in every place it has been thought a beautiful thing for each woman to make the care of her hair a most serious affair. The woman does not exist, nor has even existed, who has submitted her head to a razor, unless on account of some ill-omened and horrible calamity.

In this sense, Synesius, argues nature and custom are in harmony as no woman would ever display baldness if it occurred. Men, on the other hand, can actually assist nature and reach the ideal situation of baldness by using the razor.

Synesius was writing at a time when hair for men was often cropped quite short, at least among the elites of the later empire, of which he was a member; and the debate about women veiling was a hot topic in Christian discourse. Synesius was a highly educated individual, with experience of living in both Constantinople and Alexandria, one the imperial capital and the other a renowned, cosmopolitan center of learning. He had visited Athens and may have been initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries while there. He existed, like many of his age, across the divide between Christianity and paganism. His neo-Platonic leanings meant he had absorbed the works of the classical canon, and his training had taught him how to make persuasive and flattering speeches. It is important to understand On Baldness in this context but also to recognize the humor, parody, and arguably comic defensiveness of the piece. Above all, On Baldness is a good example of the problems we face when interpreting ancient sources discussing hair, be they written or visual.

Synesius speech is one of the longest surviving pieces of writing which address hair behavior in the ancient world.

The study of hair and hairstyles in antiquity has traditionally formed a part of research into other aspects of the physical appearance of the body. Hair is taken into account in studies of dress and adornment, in studies of gender, and of the body, often with a focus on the evidence provided by various visual media. It has rarely been given the attention which it receives in this volume.at it largest extent. The question is how we approach this enormity without falling into generalizations.

To provide some framework for this huge cultural conundrum that constitutes and ancient world, this introduction presents some of the defining elements which hold the period, the cultures, and the volume together. At the outset it is important to understand that most of these cultures shared a social and political hierarchy that privileged the male over the female. Women were rarely given active political power, although they might exert political pressure in other more subtle ways; and they were almost always subordinate to men in any given situation. For much of antiquity, across most of the cultures studied for this volume, patriarchy in its many forms, was the dominant system of power. Ancient Greek, Roman, Jewish, Christian, and Celtic societies were highly gendered and these relationshipsof power and genderwere often expressed in the language of hair. Male and female hairstyles were often diametrically opposed, most commonly noticeable in terms of length, and control of the hair was a reflection of social controlbetween the sexes, the classes, and even between citizens and noncitizens. The way the hair was worn, could, like dress, express inclusivity and exclusivity; it could symbolize belonging to a particular group in terms of sex, of age, status, of class, religious leanings, and ethnicityand any mix of these categories. The subtle interrelationships between these categories are often hard to decipher and define given the nature of the ancient source material.

Next page