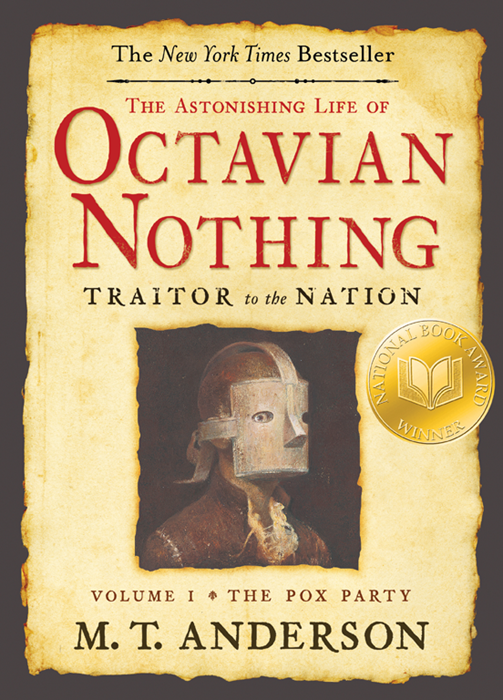

M. T. A NDERSON is the author of several novels for young adults, including The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Volume II: The Kingdom on the Waves; Thirsty; Burger Wuss; and Feed, a National Book Award Finalist and a winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Growing up in the Boston area, he was surrounded by early American history. I got my hair cut in the town that sent the first detachment of militiamen against the British, he says. My orthodontist worked in the town where Paul Revere was captured by the Redcoats. On the 225th anniversary of the Battle of Old North Bridge, after watching several reenactments, he started wondering, What would it be like to be standing there untrained facing the British with a gun I usually used to shoot turkeys? What would it be like to be standing there, not knowing that we would win? I decided to write a book from the point of view of someone who wouldnt know the outcome of the war and who had to make a hard choice between sides. M. T. Anderson lives in Massachusetts.

This is a work of ction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either

products of the authors imagination or, if real, are used ctitiously.

Copyright 2006 by M. T. Anderson

Cover illustration copyright 2006 by Grard Dubois (portrait);

photograph copyright 2008 by iStockphoto/Peter Zelei (aged paper)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted,

or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means,

graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording,

without prior written permission from the publisher.

Anderson, M. T.

The Pox party / taken from accounts by [Octavian Nothings] own hand and other sundry

sources ; collected by Mr. M. T. Anderson of Boston.

p. cm. (The astonishing life of Octavian Nothing, traitor to the nation ; v. 1)

Summary: Various diaries, letters, and other manuscripts chronicle the experiences of Octavian, from birth to age sixteen, as he is brought up as part of a science experiment

in the years leading up to and during the Revolutionary War.

ISBN 978-0-7636-2402-6 (hardcover)

[1. Freedom Fiction. 2. Slavery Fiction. 3. Science Experiments Fiction.

4. African Americans Fiction. 5. Massachusetts History Revolution, 17751783 Fiction.

6. United States History Revolution, 17751783 Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.A54395Pox 2006

[Fic] dc22 2006043170

[ T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ]

I.

THE TRANSIT OF VENUS

II.

THE POX PARTY

III.

LIBERTY & PROPERTY

IV.

THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING

I was raised in a gaunt house with a garden; my earliest recollections are of floating lights in the apple-trees.

I recall, in the orchard behind the house, orbs of flame rising through the black boughs and branches; they climbed, spiritous, and flickered out; my mother squeezed my hand with delight. We stood near the door to the ice-chamber.

By the well, servants lit bubbles of gas on fire, clad in frock-coats of asbestos.

Around the orchard and gardens stood a wall of some height, designed to repel the glance of idle curiosity and to keep us all from slipping away and running for freedom; though that, of course, I did not yet understand.

How doth all that seeks to rise burn itself to nothing.

T he men who raised me were lords of matter, and in the dim chambers I watched as they traced the spinning of bodies celestial in vast, iron courses, and bid sparks to dance upon their hands; they read the bodies of fish as if each dying trout or shad was a fresh Biblical Testament, the wet and twitching volume of a new-born Pentateuch. They burned holes in the air, wrote poems of love, sucked the venom from sores, painted landscapes of gloom, and made metal sing; they dissected fire like newts.

I did not find it strange that I was raised with no one father, nor did I marvel at the singularity of any other article in my upbringing. It is ever the lot of children to accept their circumstances as universal, and their particularities as general.

So I did not ask why I was raised in a house by many men, none of whom claimed blood relation to me. I thought not to inquire why my mother stayed in this house, or why we alone were given names mine, Octavian; hers, Cassiopeia when all the others in the house were designated by number.

The owner of the house, Mr. Gitney, or as he styled himself, 03-01, had a large head and little hair and a dollop of a nose. He rarely dressed if he did not have to go out, but shuffled most of the time through his mansion in a banyan-robe and undress cap, shaking out his hands as if hed washed them newly. He did not see to my instruction directly, but required that the others spend some hours a day teaching me my Latin and Greek, my mathematics, scraps of botany, and the science of music, which grew to be my first love.

The other men came and went. They did not live in the house, but came of an afternoon, or stayed there often for some weeks to perform their virtuosic experiments, and then leave. Most were philosophers, and inquired into the workings of time and memory, natural history, the properties of light, heat, and petrifaction. There were musicians among them as well, and painters and poets.

My mother, being of great beauty, was often painted. Once, she and I were clad as Venus, goddess of love, and her son Cupid, and we reclined in a bower. At other times, they made portraits of her dressed in the finest silks of the age, smiling behind a fan, or leaning on a pillar; and on another occasion, when she was sixteen, they drew her nude, for an engraving, with lines and letters that identified places upon her body.

The house was large and commodious, though often drafty. In its many rooms, the men read their odes, or played the violin, or performed their philosophical exercises. They combined chemical compounds and stirred them. They cut apart birds to trace the structure of the avian skeleton, and, masked in leather hoods, they dissected a skunk. They kept cages full of fireflies. They coaxed reptiles with mice. From the uppermost story of the house, they surveyed the city and the bay through spy-glasses, and noted the ships that arrived from far corners of the Empire, the direction of winds and the migration of clouds across the waters and, on its tawny isle, spotted with shadow, the Castle.

Amidst their many experimental chambers, there was one door that I was not allowed to pass. One of the painters sketched a little skull-and-crossbones on paper, endowed not with a skull, but with my face, my mouth open in a gasp; and this warning they hung upon that interdicted door as a reminder. They meant it doubtless as a jest, but to me, the door was terrible, as ghastly in its secrets as legendary Bluebeards door, behind which his dead, white wives sat at table, streaked with blood from their slit throats.