This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1943 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

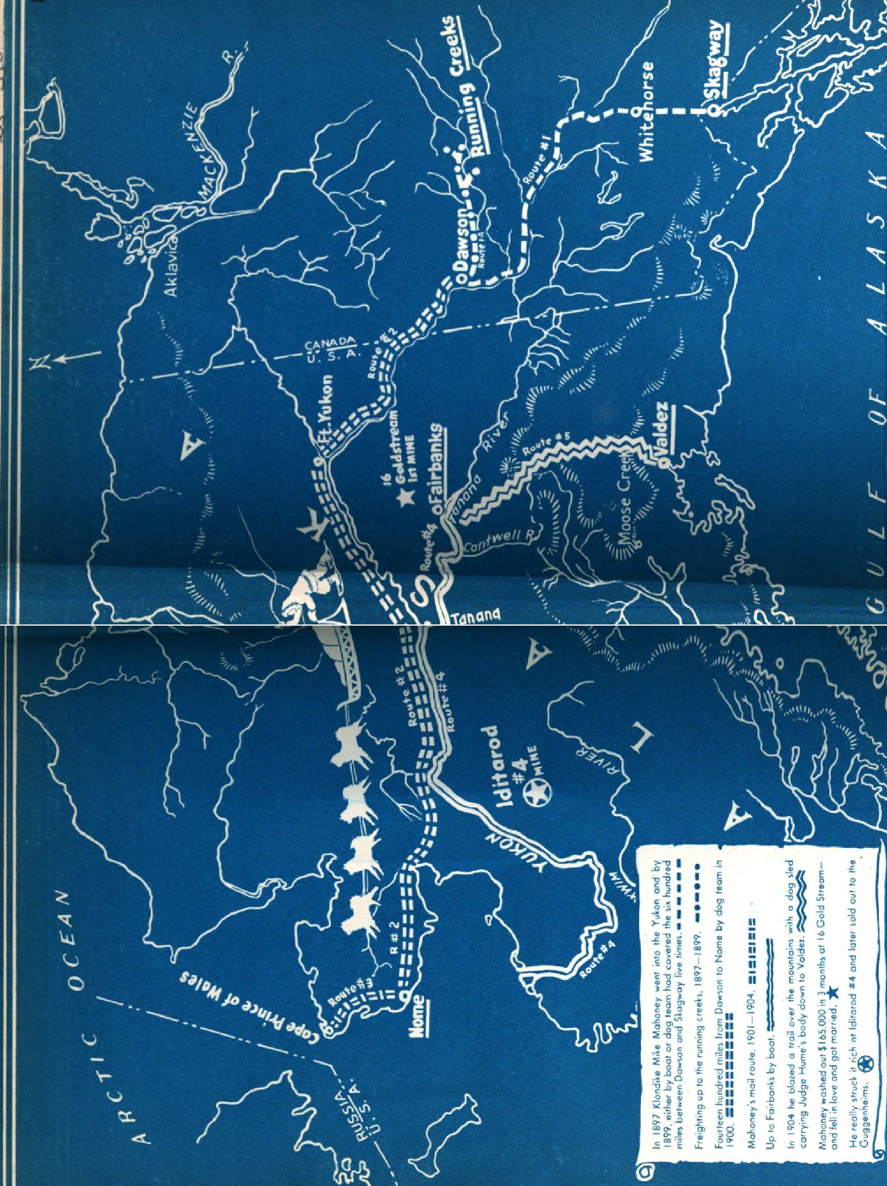

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

KLONDIKE MIKE:

AN ALASKAN ODYSSEY

BY

MERRILL DENISON

FOREWORD

THIS is the story of a legendary figure seen from inside looking out...a narrative such as Paul Bunyan, John Henry or Joe Magarac might conceivably have inspired had anyone been on hand to record their living memories.

Ordinarily, the story of the folk hero must be confined to externals. Around the figure of Paul Bunyan, for example, a voluminous literature has grown up which is exclusively outward in effect. So far as we know, the great half-god of the pine woods left no personal record behind him, no single clue to show what he was like inside. Denied a knowledge of the inner man, folklore pictures him as somewhat of an extrovert, a latter-day Hercules who moved upon his objectives with simplicity and directness, a sort of uncomplicated Superman whose inner motivations seem to spring only from the desire to outdo his own prodigious deeds.

Such an interpretation of the Bunyan character seems plausible enough, but it is based on sheer conjecture. No one knows, nor is there any way of knowing, what prompted Paul to accomplish his fabulous feats, what he felt like in the process, or how he whiled his time away between heroic outbursts. That he was marvellously endowed physically, no one can deny, but what manner of man was he in other ways? Was his Gargantuan prowess matched by an equal breadth of spirit? Who were his friends, and how did they find him as a daily companion? Was he as forthright and uninhibited as folk mythology has made him appear, or did he have his moments of doubt and introspection? In his moments of relaxation, was he agreeable and kindly, tolerant and understanding, or was he inclined, perhaps, to be saturnine and egocentric? These are questions that can never be answered. However much we may know about Paul Bunyan, the folk hero, we can never learn more about him as a human being, although human in origin he surely must have been.

Herein lies the unique quality of the story of Klondike Mike Mahoney, strong man of the north. Quite apart from its interest as a document of human adventure, it is the record of a man whose feats of extraordinary strength and physical endurance have made him a legendary character during his own lifetime and won for him a permanent place in the mythology of the last frontier, the north of the Yukon and Alaska during the years of the gold rush that began in 1897. Where U.S. Army Engineers are now bulldozing the Alcan Highway across muskegs and over mountain passes, Klondike Mike mushed as a young man and established records for speed and endurance that stand to this day. In a world where brawn and muscle were no more noteworthy than trees in a forest, his deeds and prowess were known from Skagway to Cape Prince of Wales and served Jack London, Robert Service and Heaven alone knows how many other writers with much of the factual material upon which they based their heroic fictions of the north.

Today Klondike Mike is a retired businessman in his middle sixties living in Ottawa, Canada. It was in this latter-day guise of Michael Ambrose Mahoney, successful cartage agent and building supply contractor, that I first met him in the summer of 1930 when he visited my home at Bon Echo in the Ontario backwoods. I was engaged in writing a documentary motion picture for the Dominion government, and Klondike Mike had been invited by the technical crew from Ottawa to come along and watch the shooting. He was then in his middle fifties, a heroic figure of a man, well over six feet tall and as straight as a white pine. His Irish ancestry was written in the square, strong lines of his face and his large, leonine head was crowned with a mass of white hair still slightly tinged with red. He wore an ordinary business suit, but his big frame and hard-muscled body showed wherever cloth and wearer touched, and gave the impression that city clothes were for some reason out of character. He appeared to be a man accustomed to hard work in the out-of-doors but belying this assumption, his unusually large and beautifully modelled hands looked as if they had never known an hours manual labour. Otherwise he seemed to be as presented: a well-to-do businessman off on a weekend holiday, somewhat shy and reserved with strangers, but obviously friendly and companionable.

But soon incongruities appeared. In spite of his height and solid bulk, the stranger from Ottawa moved with the light-footedness of a trained boxer or a dancer, either of which avocations seemed improbable. A chance remark revealed that sometime in his past he had been a river driver and after some urging he gave a demonstration of log birling that was amazing. On location with the camera crew, he was discovered to have a profound knowledge of the backwoods and its ways. Before twenty-four hours had elapsed he had been drafted as the principal technical adviser for the picture, whose theme was conservation.

Gradually, the figure of M. A. Mahoney, Ottawa businessman, merged into the shadowy outlines of another: Klondike Mike, erstwhile Yukon sourdough, but it was not until his last night at Bon Echo that the Alaskan character emerged with clarity. Sitting on a terrace overlooking the still Laurentian Lake, Mike Mahoney told tales of the Yukon and Alaska, of the trails of 97 and 98, of Dawson, Nome and Fairbanks, of polar bears and drifting herds of caribou, of Soapy Smith and Dangerous Dan McGrew. In answer to a query about the fabled difficulties of the Chilkoot Pass, he answered, It depended on the man. I once toted a piano over it myself. He dismissed the equally notorious White Pass crossing as tough in spots but nothing to worry a man in good condition. He spoke of a winter spent alone with a husky for a cabin-mate and casually mentioned covering seventy-five to eighty miles by dogteam in a single day. He alluded briefly to a four-hundred-mile trek as guardian to a frozen corpse with spent dogs and a hungry wolf pack for companions.

I was already familiar with the lore of the gold rush, but I was fascinated both by the tales told that night by Klondike Mike and by the way he told them. Three decades after the events such tales were already legion and time and the storytelling art had tended to mould them into the Homeric pattern of arranged mythology. In the Mahoney versions, one caught the authentic notes of observed experience, as one might have heard at Ithaca listening to Ulysses talk familiarly to his old companions.